Eros and Thanatos are opposing drives in Freudian psychology. Eros represents the life instinct – love, creativity, and survival – while Thanatos embodies the death drive – aggression, destruction, and a return to inertness. Freud believed that these forces constantly interact, shaping human behaviour through a dynamic tension between the desire to live and the pull towards death. When the Erotic Print Society decided to bring Böttger’s work to an English-speaking audience, they chose the title to encapsulate the artist’s dark subject matter.

Eros and Thanatos are opposing drives in Freudian psychology. Eros represents the life instinct – love, creativity, and survival – while Thanatos embodies the death drive – aggression, destruction, and a return to inertness. Freud believed that these forces constantly interact, shaping human behaviour through a dynamic tension between the desire to live and the pull towards death. When the Erotic Print Society decided to bring Böttger’s work to an English-speaking audience, they chose the title to encapsulate the artist’s dark subject matter.

To accompany the images, EPS added a foreword by author and photographer Oliver Maitland, and two rather good short stories, The Artist by Christopher Hart, and The Soldier by Lilian Pizzichini.

Here is Oliver Maitland’s foreword:

The Frankfurt Book Fair might seem a most unlikely venue for a disillusioned author like me to stumble over an undiscovered genius. Browsing in an obscure corner of the exhibition centre, surrounded by merchants of postcards and calendars, I chanced upon the stand of a master printer with an impressive stable of artists, although seemingly nothing particularly appropriate for the Erotic Print Society. Until, that is, he produced, from a locked cupboard, a rather grubby portfolio of the most stunning images which, from the first instant, caused the scales to fall from my eyes. This was my equivalent of Archimedes’s ‘Eureka’.

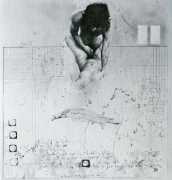

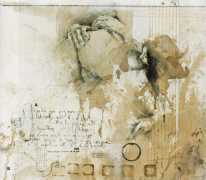

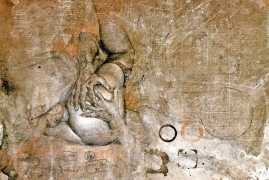

Imagine Dürer’s sketches, in silverpoint with pen and ink, now yellowed and, despite the care of generations of collectors, stained and torn by the ravages of time. Imagine that everything Dürer did had been destroyed, apart from an uncatalogued sheaf of erotic drawings. But what I found were not drawings by Dürer; they are by Klaus Böttger, a twentieth century master of similar instruments and techniques, whose recent death at the age of fifty came before he could receive the recognition which was his due. It is from more than seventy of the best of these drawings and lithographs that Eros & Thanatos has been selected.

Böttger shares with Dürer a vision of the Fall of Man as both an irresistible human catastrophe and the original confluence of sexuality and mortality. For him, though, Art extends beyond Judaeo-Christian confines, to embrace sex as a defining part of the whole human drama. Its sexual consummation is, in itself, a microcosm of the cycle of life and death. Here are echoes of Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, in which compulsive Dionysian forces overcome the rational, aesthetically-driven Apollonian condition. At our most exultant, we are also at our closest to complete annihilation.

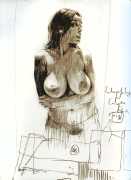

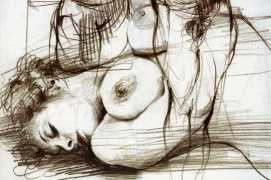

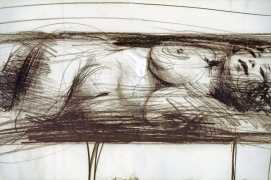

From these dark sheets emerge glowing images of the writhing limbs of a well-built woman and an amply-endowed man in the throes of the most ecstatic copulation. This, seen at such close quarters as often to preclude a sight of their faces, makes their subject matter more akin to that of the continental top shelf magazine or even the hard-core porn movie.

But the treatment could hardly be more different. Crucially, the tone is completely at variance with pornography. Where ‘porn’ is gynaecological, trivial and commercial, Böttger was serious and impassioned. This artist could not have been less interested in depicting sexual climaxes for the appetites of cheap consumerism.

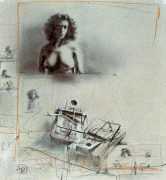

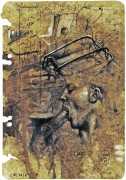

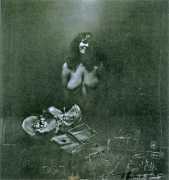

His choice of subject matter appears to have been made with the conviction that sex is part of a universal drama, in which desire is the foreplay to ‘the small death’ and Eros, the life-force, is inextricably linked to Thanatos, the realm of Death. The one complements the other. The ripeness of the lusty, splendid lovers is all too close to decay – symbolised, for example, by desiccated apples or sprung mouse-traps. The consummation of desire is a miniature of that complete obliteration which is death itself. This is often alluded to in the drawings by the inclusion of a mouse-trap, a contraption that, while it offers a tasty morsel too desirable to resist, proves lethal.

In the end ‘la petite mort’ is the way by which life renews itself – at least physically. In many of these plates, limbs drawn with astonishing verisimilitude intertwine in a giddying array of different postures. And Böttger was put on earth to celebrate the endless erotic parallels between sex and death. There is in these drawings a profound understanding that life is not well-ordered and rational. It is chaotic, passionate, unreasonable and spontaneous. This is particularly evident in the artist’s attitude towards his own incomparable technique. He is arguably one of the finest illusionistic draftsmen of this century. Although he could draw anything he wanted, as he wanted it and with great ease, Böttger also seems to have been at pains to discount his own facility. On a number of these sheets he has marked and rubbed, cut and torn, stained and scored his drawings, as if he were trying to eviscerate the wonderful products of his imagination. He was both iconographer and iconoclast; at one and the same time both proposer and disposer. At times he even goes beyond the limits of artistry to become, Shiva-like, an exterminating deity.

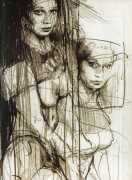

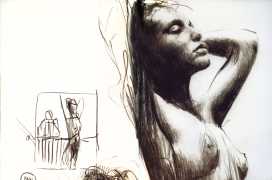

Every erotic artist (indeed any artist who is interested in drama and emotion) has the ambition to portray credible facial expressions. Few succeed, and in one sense it is as portraiture that we should look at Böttger’s oeuvre. Admittedly some of the drawings are headless, and in others, as in several of the pen and ink studies, the heads are obscured in violent movement. In some of the lithographs the models, Eve-like, reverentially contemplate their eternal womanliness and desirability; in others the girls swoon with a frenzied paroxysm which seems nearer to pain than pleasure. In my experience, these works succeed, as do few others, in capturing facial expression in extremes of emotion. Had he been an artist of, say, still lifes or marine subjects, Klaus Böttger would probably have become a household name in his own lifetime. But, because he was a chronicler of sexual desire, he has been unjustly neglected. In the realm of the erotic, Böttger’s art is the most accomplished that I have ever seen.