Chansons pour elle (Songs for Women) is the tenth poetic collection in verse by Paul Verlaine, published in 1891 by his regular publisher Léon Vanier. Composed of twenty-five medium-length poems, the collection was inspired by the poet’s liaisons with Philomène Boudin, also known as ‘Esther’, and with Eugenie Krantz, or ‘Mouton’.

Chansons pour elle (Songs for Women) is the tenth poetic collection in verse by Paul Verlaine, published in 1891 by his regular publisher Léon Vanier. Composed of twenty-five medium-length poems, the collection was inspired by the poet’s liaisons with Philomène Boudin, also known as ‘Esther’, and with Eugenie Krantz, or ‘Mouton’.

With an erotic theme in the same vein as Parallalement (1889), but devoted to specific women, the language and symbolism of Chansons pour elle marked Verlaine’s final abandonment of all hope of salvation through religious faith, freeing him to write about physical passion and desire without the accompanying guilt.

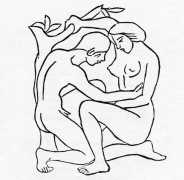

In 1906 the Parisian publisher Ambroise Vollard commissioned Maillol to illustrate a deluxe edition of Chansons pour elle, issued in 1907 in a small, carefully controlled print run aimed at bibliophiles. Maillol’s illustrated Verlaine’s poems with woodcuts, a medium he was exploring intensively at the time. They are spare and classical in tone, naked or lightly draped female figures, often standing or reclining in shallow, almost timeless spaces. Rather than illustrating specific moments from Verlaine’s poems, Maillol provided a parallel vision – sensuous but calm. His women are solid, self-contained and sculptural, anticipating Maillol’s mature sculpture. Sexuality is conveyed through weight, balance and repose rather than gesture or narrative. This restraint was deliberate – Maillol rejected the symbolist eroticism of contemporaries like Félicien Rops, offering instead an idealised, Mediterranean sensuality.

The Maillol-illustrated Chansons pour elle was reissued in 1939 in a newly typeset edition in the Chez l’Artiste series, in a limited numbered edition of 175 copies. Then in 1966 it was issued as part of the Les Peintres du Livre series, published by L.C.L /Messein, in a numbered and boxed edition of 3,000 copies. The new introduction to the 1966 edition explains, ‘The perfect serenity of Maillol’s soul shines through in his woodcuts, displaying his great virtuosity. Verlaine had managed to touch him both with his somewhat raw sincerity and with his poetic genius. “Everything that is art,” Maillol said, “everything that is beautiful gives me a thrill, a sensation as when one enters the sea to bathe.”’