The censorship of erotic art in Germany

Hans-Jürgen Döpp

Censorship of art, and especially of erotic art, is a favourite activity of authorities who believe they alone hold the key to public taste and acceptability. In reality censorship tends to be as much about control as about safety, denying creative expression and personal exploration in the guise of public morality. Germany has a long history of artistic censorship, and it repays us to give attention to what has happened in the past to ensure that our judgements in the present are sound and well-founded.

The name of Hans-Jürgen Döpp will be familiar to anyone interested in the history and dissemination of erotic art. His many books include 1000 Erotic Works of Genius, Objects of Desire, The Kiss, Temple of Venus and Paris Eros, and after fifty years of careful gathering has amassed a large and fascinating erotic art collection. Hans-Jürgen is based in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, and for many years taught sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University. As well as collecting, teaching and writing he has curated many exhibitions and helped develop and collect for several erotic art museums. He now publishes a wide range of specialist publications under the Venusberg imprint (www.venusberg.de).

The name of Hans-Jürgen Döpp will be familiar to anyone interested in the history and dissemination of erotic art. His many books include 1000 Erotic Works of Genius, Objects of Desire, The Kiss, Temple of Venus and Paris Eros, and after fifty years of careful gathering has amassed a large and fascinating erotic art collection. Hans-Jürgen is based in Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany, and for many years taught sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University. As well as collecting, teaching and writing he has curated many exhibitions and helped develop and collect for several erotic art museums. He now publishes a wide range of specialist publications under the Venusberg imprint (www.venusberg.de).

We are delighted that Hans-Jürgen has contributed this piece to our website.

Knowledge has always been dangerous to the powerful, which is why its dissemination and appropriation have always been controlled. Insofar as the knowledge of sexuality and eroticism has been considered rebellious, it is an area which has especially been subject to censorship.

By far the most powerful censor in modern European history has been the Roman Catholic Church. The first comprehensive list of forbidden books, the Librorum Prohibitorum, was published at the Council of Trent in 1564. The last edition of the index appeared in 1948; it contained many books with erotic scenes, including novels by Balzac, Stendhal and Zola. After the ecclesiastical courts of justice lost their authority, censorship was exercised through governments or the crown. For a long time, however, convictions continued to be made on the basis of anti-authoritarian views rather than erotic content.

At the head of reactionary authority in Germany in the early nineteenth century was Chancellor Metternich, who campaigned to suppress liberal tendencies by introducing pre-censorship, whereby potentially actionable works were to be submitted before publication. The best-known victims of these restrictions were Georg Büchner and Heinrich Heine, whose works included many tirades against censorship. Heine ridiculed the censors in Chapter 12 of his 1826 Reisebilder (Travel Pictures), which has all the text pre-censored except for the opening words ‘Die deutschen Zensoren’ (The German censors) and the word ‘Dummköpfe’ (fools) .

At the head of reactionary authority in Germany in the early nineteenth century was Chancellor Metternich, who campaigned to suppress liberal tendencies by introducing pre-censorship, whereby potentially actionable works were to be submitted before publication. The best-known victims of these restrictions were Georg Büchner and Heinrich Heine, whose works included many tirades against censorship. Heine ridiculed the censors in Chapter 12 of his 1826 Reisebilder (Travel Pictures), which has all the text pre-censored except for the opening words ‘Die deutschen Zensoren’ (The German censors) and the word ‘Dummköpfe’ (fools) .

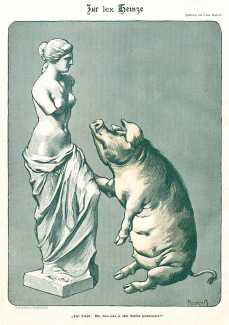

Pre-censorship was abolished in 1848, but through the penal code the state maintained the option of post-censorship. When the German Reich was founded in May 1871, Section 184 of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code) made ‘the distribution of lewd writings, images or representations’ a punishable offence. In June 1900 the section was supplemented by the so-called ‘Lex Heinze’, named after a Berlin pimp of that name, who was accused and convicted of committing bodily injury resulting in death. As well as making pimping a criminal offence, it censored the public display of anything ‘immoral’ in art, literature and the theatre. After numerous public protests and resistance, the Reichstag passed a looser version of the draft law, adding a ‘morality clause’ into the Strafgesetzbuch as a compromise.

According to Section 184a, it was now forbidden to pass on or sell to young people under the age of sixteen ‘writings, images or representations which, without being lewd, grossly offend a sense of shame’. Thus the already vague terms ‘lewd’, ‘offend’ and ‘shame’ became the core of what were to become the youth protection laws. Opponents from the liberal bourgeoisie and the social democrats criticised the arbitrary interpretations behind the new censorship proposals, but albeit in a compromise version the law was passed.

In a 1902 pamphlet Lucinde and the Lex Heinze the literary historian Heinrich Meyer-Benfey wrote ‘If the viewer or reader is not able to see and enjoy art as art, but only see the crude subject matter as a result of inadequate aesthetic education, then such art ceases to be art. We lose sight of what art is. Those who have no artistic sense should have no say in deciding what is and is not art.’ He pointed out that many allegedly ‘immoral’ images, including sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Wilhelm Lehmbruck, Bertel Thorvaldsen and Antonio Canova had been declared ‘indecent’ by the Berlin Regional Court, because ‘the young must be protected from them, as the depiction of the naked body arouses their lust ’.

In 1919 the situation improved somewhat with the signing of the Weimar Constitution, Article 118 of which guaranteed the right to freedom of expression ‘by word, writing, print, images or in any other way’, but only ‘within the limits of general laws’. According to the historian Werner Fuld, any idea that there was little or no censorship in Weimar Germany is misleading, because freedom of expression was only really relative to the strict provisions of pre-Weimar censorship.

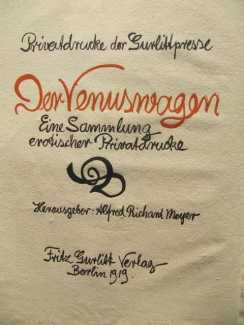

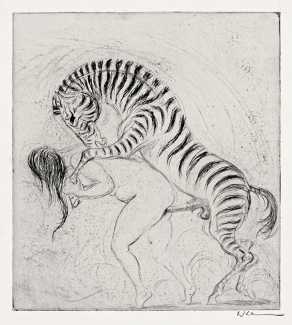

In his 1931 classic survey of erotic literature, Irrgarten der Erotik (The Erotic Labyrinth), Paul Englisch describes the trial of the Berlin-based Gurlitt when in 1919 it published the nine-volume Der Venuswagen (The Chariot of Venus). The entire production was condemned, and what (mercifully little) was left in the company’s warehouse was confiscated. The court ruling was that ‘The decisive factor should be the degree of artistic perfection. Those creations that touch the sexual should be allowed only if it is guaranteed that they will only be in the hands of experts, or at least of mature men and women’. Of course, since the Gurlitt portfolios were sold widely through the book trade and the brochure advertising it through bookshops, anyone who could afford it, whether expert or not, mature or not, could procure a copy of Der Venuswagen – which is precisely what the court, in interpreting the law, said it was attempting to avoid.

George Grosz’s 1923 portfolio Ecce Homo met a similar fate; it was tried in court for ‘indecency’ and Grosz was ordered to pay a fine of 2000 Reichsmarks. As the journalist Kurt Tucholsky wrote in the newspaper Weltbühne, ‘This is not about the protection of adolescents; it’s about the limitation of adults. The law, supposedly against filth and trash, fails under its own definitions’.

The 1920s trials against ‘blasphemous’, ‘indecent’, and similar material ‘dangerous to the state’ became part of the legal apparatus of the state. The officials of the Sittlichkeitskommission (Morality Commission) distinguished themselves by their zeal – the Berliner Zentralpolizeistelle zur Bekämpfung unzüchtiger Bilder und Schriften (Berlin Central Police Office for Combating Indecent Images and Writings) transferred one copy of each of the condemned publications to the ‘poison cabinet’ of the State Library, supposedly to be burnt. The corresponding collection at the Berlin Police Headquarters was renowned – six huge double cupboards filled with 8,200 publications which had been confiscated as ‘lewd’.

Most of the books and portfolios that are now so highly valued by collectors can be found in the ‘directory of documents confiscated on the basis of Section 184 of the Reich Criminal Code, which are suspected of being indecent and therefore to be rendered unpublishable’ – better known as ‘The Polunbi (Polizeipräsidium zur Unzüchtiger Bilder) Catalogue’. Here are some of the best-known titles from the Polunbi list:

- ‘W. H.’, Phantasien des Kunstmalers, published by P. Hellwig, Berlin-Neukölln. Prohibited in 1926 as unpublishable by District Court I, Berlin; Polunbi Catalogue page 113.

- Paul Avril, De Figuris Veneris (1907). Judged in Munich in 1923 as unpublishable; Polunbi Catalogue page 38.

- Gyula Derkovits, Pandämonium (1924). Judged in Dresden in 1926 as unpublishable; Polunbi Catalogue page 109.

- Ludwig Lutz Ehrenberger, Das trunkene Lied (1925). Judged in Berlin in 1932 as unpublishable; Polunbi Catalogue page 89.

- Hans Pellar, Der verliebte Flamingo (1923). Judged in Munich in 1929 as unpublishable; Polunbi Catalogue page 41.

- Gottfried Sieben, Balkangreuel (1909): Judged as unpublishable.

- Helmuth Stockmann, Puder (1918). Judged in Leipzig in 1927 as unpublishable; Polunbi Catalogue page 116.

- Heinrich Lossow, Ein treuer Diener seiner Frau (1890). Judged in Karlsruhe in 1933 as prohibited; Polunbi Catalogue page 25.

In 1926 the regulation of ‘dirt and trash’ was tightened by an amendment to Article 118 of the Weimar Constitution. The text of the new law, Article 122, ruled that ‘Young people are to be protected against exploitation and against moral, mental or physical neglect, to which end both state and municipality must make the necessary arrangements’. The result was to ban everything on the Polunbi list, even for ‘mature adults’. Historian Peter Jelavich has written that this was ‘a turning point in the history of German censorship, which under the guise of “youth protection” now made access to writings, images and media even more difficult, a situation which continued well into the modern period.’

A game of cat and mouse began for endangered artists. Many works were published anonymously or pseudonymously. To be on the safe side Otto Schoff’s portfolios Orgien and Liebesspiele der Venus appeared without any indication of place, publisher or year. The Fritz Gurlitt publishing house published Schoff’s portfolio Knabenliebe anonymously. Heinrich Zille’s Hurengespräche appeared under the pseudonym W. Pfeifer and with a false publication date of 1913; nevertheless the work was banned by the Prussian censors on the spot. After he came into conflict with the judiciary with his portfolio Erbsünde, Walter Klemm only dared to produce a single copy of the already-finished plates for the Die Dirne. Censorship acted as self-censorship, and it is salutory to consider how many similar works never saw the light of day.

As early as 1931 Paul Englisch wondered ‘Has the world become more “moral” as a result of these prohibitions? Experience suggests that every prohibition results in deep questioning in cultural circles, which are generally of the opinion that moral and cultural ennoblement can only be promoted through the exploration of the passionate impulses affecting human behaviour. Such exploration is entirely natural, and rather than denying and suppressing our innate natural instincts results in the most important works of recognised poets and artists.’ Of course, after the National Socialists came to power in 1933 discussion of the artistic exploration became superfluous – any idea of intellectual freedom was lost in the flames of public book burnings.

From the German Empire, through the Weimar Republic, to the Federal Republic of Germany, there is a continuity of censorship. After the Second World War, in 1954 the new Gesetz über die Verbreitung jugendgefährdender Schriften (Law on the Dissemination of Writings Harmful to Young People) led to the establishment of the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften (Federal Inspectorate for Writings Harmful to Young Persons), renamed in 2003 the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien (Federal Inspectorate for Media Harmful to Young People).

The search was now on for writings ‘considered unhealthy for morally endangering young people’, the Inspectorate claiming that the books it listed led to ‘the socio-ethical disorientation of young people’. Especially in the first few decades of its activities, the list revealed a canon of values considered antipathetic to the social development of the Federal Republic, a reactionary worldview that tended to be hostile to new art forms.

The law relating to censorship has regularly created problems for those asked to enforce it. In July 1969 the Federal Court of Justice was asked to rule on a new translation of John Cleland’s 1748 novel Fanny Hill, concluding that ‘the criminal law is not intended to enforce a moral standard for adult citizens, but it does exist to protect the social order of the community’. The lack of competence of the courts and law enforcement authorities is often a serious issue. Public prosecutors and judges must balance questions of the guarantee of artistic freedom with real danger to young people. Sometimes a judgement even refers back to earlier – and just as suspect – decisions. In 1983, for example, a new translation of the 1921 Italian novel Kokain was added to the censored list, the ruling being based on an earlier decision of 1954, which in turn was based on a judgment of the Reich Inspection Office in Berlin from June 1933, thus perpetuating a blatantly fascist decision.

It can be hard to determine the suitability of books for young people around the subject of sexuality and intimacy. Education of parents and educators and a sex-friendly upbringing are seen as the most tried and tested measures to help young people’s healthy development. One thing is certain – people who have more experience of erotica tend to be more tolerant and liberal with regard to the behaviour of other people than people with little experience of it. It is understandable that in the past the moral standards of a predominantly conservative social class prevailed, but in today’s world we need a more tolerant and inclusive approach. And we need to think of erotica in relation to other perceived ‘social harms’. As the constitutional lawyer Richard Schmid wrote in 1968, ‘If you consider how the state not only tolerates undisputed physical and psychological harm from alcohol and cigarettes, but also draws high revenues from them, then the criminal prosecution of intangible, subjective, often purely class-related sexual material seems absurd.’

To illustrate the complexities of recent German censorship law, it is worth looking at the infamous ‘Mutzenbacher-Entscheidung’ (Mutzenbacher Judgement) of 1990. Josefine Mutzenbacher, or The Story of a Viennese Whore, was published privately in Vienna in 1906, and in the 1960s, after two criminal courts had judged it to be pornographic, was included in the list of writings harmful to minors by the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften. At the end of 1978 the publisher Rowohlt reissued Josefine Mutzenbacher, adding a new explanatory foreword and a glossary. Because they wanted to distribute the book unhindered, Rowohlt applied to the Bundesprüfstelle to remove their version from the list of writings harmful to minors, on the grounds that the novel was both an important social commentary and a work of art. After commissioning two expert reports, the Bundesprüfstelle came to the conclusion that it was not a work of art, and rejected the request. The reason given was that the novel was seriously harmful to young people because it emphasises child prostitution and promiscuity. The novel, they said ‘was little more than a collection of pornographic descriptions of the sexual activities of the heroine.’

To illustrate the complexities of recent German censorship law, it is worth looking at the infamous ‘Mutzenbacher-Entscheidung’ (Mutzenbacher Judgement) of 1990. Josefine Mutzenbacher, or The Story of a Viennese Whore, was published privately in Vienna in 1906, and in the 1960s, after two criminal courts had judged it to be pornographic, was included in the list of writings harmful to minors by the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften. At the end of 1978 the publisher Rowohlt reissued Josefine Mutzenbacher, adding a new explanatory foreword and a glossary. Because they wanted to distribute the book unhindered, Rowohlt applied to the Bundesprüfstelle to remove their version from the list of writings harmful to minors, on the grounds that the novel was both an important social commentary and a work of art. After commissioning two expert reports, the Bundesprüfstelle came to the conclusion that it was not a work of art, and rejected the request. The reason given was that the novel was seriously harmful to young people because it emphasises child prostitution and promiscuity. The novel, they said ‘was little more than a collection of pornographic descriptions of the sexual activities of the heroine.’

Rowohlt took legal action against this decision, and having been defeated in the lower courts lodged a constitutional complaint for the violation of artistic freedom. The Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court) ruled, in line with earlier interpretations, that art is the ‘result of free creative design in which impressions, experiences and fantasies of the artist’. In relation to Josefine Mutzenbacher it ruled that the novel conveys these characteristics, and the fact that it is also pornography does not remove its artistic status. The book’s recognition as art should not be made dependent on state control of style, level and content. Despite the decision of the Bundesverfassungsgericht, in 1992 the Bundesprüfstelle put the novel back on the banned list, this time on the grounds that it was dangerous child pornography. It was not until November 2017 that the Bundesprüfstelle finally took the novel off the list of media harmful to minors.

In the meantime, the German Jugendschutzgesetz (Youth Protection Act), first enacted in 1952, has been modified several times, with a greater focus on new media. In 2003 it was merged with the Gesetz über die Verbreitung jugendgefährdender Schriften und Medieninhalte (Law on the Dissemination of Writings and Media Content Harmful to Minors) in the new Jugendschutzgesetz, which came into force at the same time as the Jugendmedienschutz-Staatsvertrag der Länder in Kraft (State Treaty on Youth Media Protection).

Under to the new provisions of the Jugendschutzgesetz, a Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien (Federal Testing Office for Media Harmful to Young People) now decides on what should be prohibited. The most important relevant section is as follows:

Section 18 (1) of the Jugendschutzgesetz (Youth Protection Act)

Providers and online media that endanger the development or upbringing of children and adolescents in becoming self-reliant and socially capable persons must be included in a list of media endangering minors by the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien. This includes media which is immoral, disturbing, or encourages violence, crime or racial hatred, as well as media in which

1. acts of violence such as scenes of murder and violence are presented in detail for their own sake

2. self-justification is the only proven means of enforcing supposed justice.

(3) A medium may not be included in the list

1. solely because of its political, social, religious or ideological content,

2. if it serves art or science, research or teaching.

Thus the courts still have to deal with two conflicting freedoms. On the one hand the constitutional requirement of the protection of minors must be taken into account, and on the other material which serves art and science, research and teaching must be freely available. It tends to come down to individual cases; with regard to pornographic texts in general the Bundesverfassungsgericht admits that the extent of moral risk to young people cannot be proven empirically, and can only be ascertained with expert help. The solution cannot be to keep everything that does not equate with an ideal world away from children and young people, because if they are not allowed to experience anything risky or challenging they will learn relatively little both about art and about the reality and complexity of everyday life.

The aim of the Jugendschutzgesetz is to develop ‘a self-reliant and socially competent personality’. As author Heinrich Böll wrote in a 1971 article ‘The Hypocrisy of the Liberators’, ‘The legislation is characterised by two properties – ignoring and withholding. It ignores the complexity of human sexuality, and withholds important rewards which are presented solely as forbidden.’ The politician and criminal lawyer Adolf Arndt adds, ‘A sexual morality that is not freely chosen, but enforced through repression by means of criminal penalties, ceases to be a morality. It merely breeds cultural hypocrites’.