The inspiration of King Pausole

Pierre Louÿs’ novel Les aventures du Roi Pausole (The Adventures of King Pausole), first published in 1900, might at first glance look like an eighteenth century parody in the style of Voltaire or Diderot. However, Pausole was very much a contemporary work. The king of the country of Tryphême was a neighbour of France, and of Emile Loubet, the French president at the time. It’s simply that King Pausole’s country did not appear on maps, it was too prosperous and successful for that. ‘To know of its existence might attract tourists, so geographers have preferred to leave the country in blue, lost in the Mediterranean’.

Pierre Louÿs’ novel Les aventures du Roi Pausole (The Adventures of King Pausole), first published in 1900, might at first glance look like an eighteenth century parody in the style of Voltaire or Diderot. However, Pausole was very much a contemporary work. The king of the country of Tryphême was a neighbour of France, and of Emile Loubet, the French president at the time. It’s simply that King Pausole’s country did not appear on maps, it was too prosperous and successful for that. ‘To know of its existence might attract tourists, so geographers have preferred to leave the country in blue, lost in the Mediterranean’.

Tryphême, this fantasy land so close to France, is ruled by a king who wishes above all the complete happiness of his people, including of course himself. That’s why he has 366 women, one for every day of the year plus one for leap years. This means that he can avoid confronting the prospect of having to make constant choices about which to spend time with.

King Pausole grants and recommends a similar freedom for all his subjects, and the Tryphême penal code boils down to two rules: ‘Do not harm your neighbour, and that being understood, do what you like.’ Nothing could be simpler – nor more complicated. Because King Pausole makes up some rules to suit himself; after all, he is the king. While he allows most Tryphêmoises to wear what they like, young women, and especially his daughter Aline, are not allowed to wear anything at all, because (he argues) that would detract from their beauty. The well-argued double standard extends to his harem; while marriage and monogamy are not particularly recommended in his country, it is forbidden to his 366 women to see men at all, except for the one night a year they spend in the company of the king. So King Pausole reigns without question, dispensing justice under a cherry tree rather than an oak tree (because the tree is shade as much as another, and in addition it gives good fruit). Until his small world collapses.

One day his daughter, the fair Aline, escapes her gilded prison in the company of the beautiful dancer Mirabelle. After much hesitation, Pausole goes looking for her, mounted on his mule and accompanied by two advisors – his page Giglio and the harem eunuch Taxis. Giglio is the libertine servant and jester, Taxis embodies order and discipline. Their journey leads this unlikely trio, accompanied by forty soldiers, into a series of adventures of relatively little consequence before Pausole recognises the futility of his quest. The harem revolts. The trio meet the young dairymaid Thierrette, the guardian of the Rosine raspberries, the sisters Galatée and Philis, and many other of the king’s subjects. When they finally arrive in the city the citizens confirm that they love their king precisely because he guarantees freedom of manners and commerce. Nudity is the norm, only ugly people are asked to put on clothes (and that is up to them), and non-exclusive romantic relationships are highly recommended.

And the conclusion? ‘Here ends the extraordinary adventure of the King Pausole in which he set out to find his daughter, and travelled seven kilometers on a mule from his palace to his great city’. On his return to the palace, Pausole emancipates his daughter and gives the harem its freedom, now without the eunuch Taxis who is sent back to France.

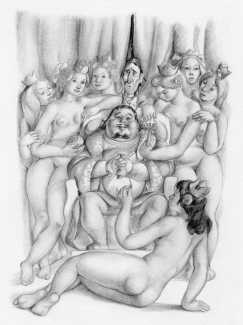

The Adventures of King Pausole is bathed in an ambient eroticism from start to finish – often more suggestive than descriptive, but always present. Along the way Louÿs develops a familiar theme: that of lesbianism through the flight of the princess Aline with Mirabelle, who becomes her initiator. Beyond this, Tryphême appears as a land of uninhibited pleasure, where love is something natural and obvious. Behind a deceptively light treatment hide Louÿs’ reflections on love, nudity, sexuality and morality. He creates a special form of utopia, responding to ideas set out elsewhere in his writings, in which he defends unrestrained sensuality by removing any notion of sin and praising free love.

And in Tryphême the nakedness does not apply just to the beautiful bodies of its beautiful inhabitants; it extends to simplicity, honesty and transparency in the way the country is organised (or at least the way it might be if the royal double standard did not apply). With a light playfulness, Louÿs’ book is at the same time a satire against prudery, bureaucracy and the arbitrary power of institutions. When he meets Lebirbe, President of the League against Domestic License, who proposes to impose mandatory nudity on young people, Pausole declares passionately, ‘Imposing nudity on the highway? Why, Lebirbe, that would be as ridiculous as forbidding it!’

In many respects The Adventures of King Pausole is an anarchist tract published seventy years too early for the free love revival of the late 1960s, and Pierre Louÿs an author whose time had not yet arrived. His understanding of the necessary link between public and private morality was way ahead of its time, especially in relation to male privilege. Pausole is most definitely a novel which should not be forgotten.

A brief footnote: in 1973 in the French city of Metz, an ‘anarchist individualist review’ took the name of Pausole, starting its numbering at 366. Just four issues were published.

As you will see from the number of Pausole portfolios on this website, Les aventures du Roi Pausole became one of the most illustrated books in French literature between the 1920s and the 1960s. This is hardly surprising; the book was never out of print and widely read, and the subject matter is perfect both for the illustrator and the book’s readership, especially with so much nudity in evidence. As well as the ten French illustrated versions shown here, the best English translation, illustrated by Clara Tice, is also included.

King Pausole and the Wican Rede, by David Richard Jones

‘Eight words the Wican Rede fulfill: An ye harm none, do what ye will.’

The Wican Rede has many ancestors: the earliest progenitors are probably Hippocrates, St Augustine and the utterance of Jesus in the Lord’s Prayer. In the Hippocratic oath we find ‘Harm None’, or as it is sometimes translated ‘First do no harm’. In the Lord’s Prayer we have the first surviving ancient appearance of the word Θελημα as ‘thy will.’ St Augustine’s Sermon on St. John’s first epistle has the dictum ‘Love and do as ye will’, which is amazingly close to the phrases familiar to Thelemites.

Rabelais is commonly given credit for the initial formulation of the libertarian ethical maxim of thelema, being the sole rule of his fictional Abbey of Thelema: ‘fay çe que vouldras’, variously translated from archaic French as ‘do what thou wilt’, ‘do what you please’, ‘do as you wish’, etc. Aleister Crowley expanded this idea into the modern religion of Thelema from its reference in his (or Aiwass’s depending on your point of view) holy text The Book of the Law, which has not only ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law’, but also ‘There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt’. This is often asserted to be the root of the Wican rede because Gardner borrowed so much from Crowley and The Book of the Law in his formulation of the rituals of Gardnerian Wica. Strangely on Gardner’s O.T.O. charter (signed by Crowley as Baphomet), Gardner miscopies this phrase as ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the law’. There is even ‘There is no law in Cocaigne save, Do that which seems good to you’, from the satire on Crowley’s Gnostic Mass in chapter 22 of James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen.

As influential as all these sources may be, Gerald Gardner tells us quite clearly what the direct predecessor actually is: ‘[Witches] are inclined to the morality of the legendary Good King Pausol, “Do what you like so long as you harm no one”. But they believe a certain law to be important, “You must not use magic for anything which will cause harm to anyone, and if, to prevent a greater wrong being done, you must discommode someone, you must do it only in a way which will abate the harm”’. (Gerald B. Gardner, Witchcraft Today)

King Pausol is not, in fact, legendary per se but the literary creation of the French novelist by Pierre Louÿs (1870–1925). Pierre Louÿs was the author of a number of popular turn-of-the-century fabulist erotic novels. King Pausol or Pausole in the French is from his novel Les Aventures du roi Pausole: Pausole (souverain paillard et débonnaire), (1901, reprinted in 1925 and numerous times since), or the Adventures of King Pausole (the bawdy and good natured sovereign). His style was heavily influenced by Rabelais which probably accounts for the inclusion of the maxims that eventually became the Wican rede, as The Adventures of King Pausole borrows many themes and ideas from Gargantua and Pantegruel; the variant of the thelemic dictum being but one among many.

The novel takes place in fantastic kingdom of Tryphême, which has a simple code:

- — Ne nuis pas à ton voisin.

- — Ceci bien comprix, fais ce qu’il te plaît.

The Lumley translation has this as

- Thou shalt not harm thy neighbour

- This being understood, do as you wouldst.

but my poor French would indicate that in the second maxim ‘wouldst’ is a bit weak for ‘plaît’ and that it should probably be rendered something like ‘This being understood, do as you please’ or ‘do as you like’.

King Pausole applies this to his own life and has a variety of sexual relations with the 366 wives (one for each day with an extra for leap year) in his harem. The conflict in the story comes when a handsome young stranger arrives in the Kingdom and Pausole is faced with applying this principle to his beautiful daughter Aline when she and the handsome stranger fall in love. It all works out well in the end, of course, and the story is a comedy of erotic errors wherein old King Pausole must learn the hard way that the great Code of Tryphême has no value if it is not a true and universal law.

From the standpoint of Wican ethics it is clear that Gerald Gardner came across this story in his wide and varied exposure to culture, but it is far from clear exactly how this exposure happened. The text exists in a number of English translations: Pierre Louÿs: The Adventures of King Pausole. London : The Fortune Press, 1919. Collected works of Pierre Louÿs. New York : Liveright, Inc, 1932 (illust. H. G. Spanner). New York : Shakespeare House, 1951. New York: Liveright, 1952; though none of these are found in Gardner’s extant library list.

The book was also used as the basis of an Operetta: Les Aventures du roi Pausole (1930) by the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) and the French librettist Arthur Willemetz (1887–1964). Gardner could certainly have seen a performance given the time frame. Several recent recordings are available, and the operetta is popular enough to rate modern performances. It is unclear how much French Gardner knew and the Bracelin/Shah biography doesn’t provide much help, but it was common for male Brits to have passable schoolboy fluency in the language, as witnessed by decent translations from that language by Gardner’s near contemporaries Crowley, Mathers, Wescott and Waite. Arthur Honegger was a lesser-known modern classical composer, associated with Schoenberg and Stravinsky (both of whom were also heavily influenced by pagan themes). Willemetz was a famous librettist of the French comedic theatre, especially the infamous Moulin Rouge, and a popular biography by his daughter is available.

The book was also made into a film directed by Alexis Granowsky (released 1933) featuring the Swiss born Austrian actor Emil Jannings (1884–1950, Oscar for best actor in The Way of All Flesh, 1927 and The Last Command 1928): released variously under the titles Die Abenteuer des Königs Pausole (Germany), König Pausole (Austria), King Pausole (Great Britain) and The Merry Monarch (USA). Again it is quite possible if not probable that Gardner saw the British release of this very popular film. It is available on video, though it may be silent, appearing on the cusp of the transition to talkies and featuring actors and a director who made their names in the silent era.

The only remaining question is who converted the code of Tryphême into the rhymed version that is so familiar to pagans worldwide. John J. Coughlin in his excellent study of the genesis of the Wican rede shows fairly convincingly that Doreen Valiente, with her talent for poetic composition, is the probable author. He also argues soundly that the Thompson/Porter assertion of a traditional family witchcraft source for the rede is not only unsupported but almost certainly untrue. The other possibility is that Gardner was following his formula for composing spells: ‘Always in rhyme they are, there is something queer about rhyme. I have tried, and the same seem to lose their power if you miss the rhyme. Also in rhyme, the words seem to say themselves. You do not have to pause and think: “What comes next?” Doing this takes away much of your intent.’ (Gerald B. Gardner, 1957, The Weschcke Letters)

To read the online version of this essay, complete with notes and references, follow this link.