Japanese erotic art and its two-way influence on Western erotic artists

Shunga Gallery is a sort of sister resource to Honesterotica – whereas we concentrate on western erotic illustration, Shunga Gallery complements us with a comprehensive resource for Japanese and Japanese-inspired erotic art. The Shunga Gallery website was conceived and created by specialist art dealer and historian Marijn Kruijff.

Shunga Gallery is a sort of sister resource to Honesterotica – whereas we concentrate on western erotic illustration, Shunga Gallery complements us with a comprehensive resource for Japanese and Japanese-inspired erotic art. The Shunga Gallery website was conceived and created by specialist art dealer and historian Marijn Kruijff.

In 2000 Marijn started selling ukiyo-e art (Japanese woodblock prints and paintings from the late seventeenth to late nineteenth century) from the antiques business AK-Antiek in the Dutch town of Coevorden and the associated website at www.akantiek.nl. Inspired by its aesthetic and commercial appeal, over the years he focused more and more on the erotic subgenre called shunga, the genre within ukiyo-e that explores the erotic secrets of ancient Japan.

Over the next two decades Marijn’s shunga content was removed from several platforms including YouTube and Tumblr, and it became increasingly clear to him that there wasn’t anywhere where artists and lovers of shunga and related sensual art could freely share and express these interests, somewhere to enjoy the aesthetics of shunga without restraint.

So in 2016 he started the website and blog Shunga Gallery, which has now published more than six hundred articles and five eBooks. The growing interest in his mission can be seen in the number of new subscriptions to the email newsletter. In 2020 the number of new daily subscriptions more than doubled. In 2021 Shunga Gallery will be adding a forum, a unique shunga price indicator, and new eBooks.

We asked Marijn to write this short introduction to the links between Japanese shunga and Western erotic art and illustration, which we hope you enjoy. You will of course find much more, and some truly amazing imagery, at the Shunga Gallery website. Thank you Marijn!

The Shunga Gallery website can be found here.

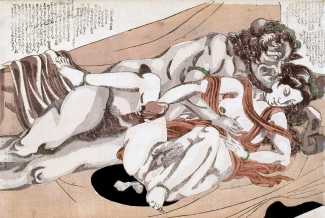

Japanese shunga and the West

The symbiosis and exchange of ideas between artists worldwide has existed for a very long time, helped enormously by the invention of the printing press. This was no different within artistic communities in both East and West, but over time the exchange between East and West gradually increased. Interestingly it was the secluded Japanese who came into contact with Western art first, rather than the other way around.

For over 250 years from the mid-seventeenth century, Japan’s only window to the outside world was Deshima in Nagasaki Bay, and Japanese artists had very little exposure to Western art. The artificial island of Deshima was populated exclusively by the Dutch, so it was the books of copper engravings brought by Dutch traders that were viewed with great interest by local artists. It wasn’t long before Japanese artists started to try out some of the innovations they saw.

The stylistic parallels between Japanese and European works can be seen for instance in the erotic caricatures of têtes composées, produced during the French Revolution, which depicted famous intellectuals, political and religious figures. The eminent Japanese artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861), an avid admirer of Western prints, is believed to be inspired by such caricatures for his composite portraits (yose-e) from 1847–8.

It is quite likely that Kuniyoshi came across the caricature of Abbot Jean-Sifrein Maury (L’Abbé Mauri), a head created on the principle of phalluses substituted for the nose, lips, hands and neck, which gave him the idea for his yose-e design ‘He Looks Scary but is Really Quite a Nice Person’.

In the early nineteenth century two other important ukiyo-e artists came into contact with European art and incorporated elements of its style into their erotic art. The first was Yanagawa Shigenobu (1787–1833), whose oban-sized series Willow Storm, produced in the late 1820s, includes a depiction of a Western couple in which the artist attempts to mimic the shading of Western copperplate etching.

The second was the prolific and outstanding Meiji shunga artist Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–89), who produced four luxurious scroll prints depicting orgiastic scenes of men in Western-style clothing and women in both Japanese and Western-style dress, with in the background European-style sculptures and weird imagery including a European couple making love on top of an elephant.

The influence of shunga on European art

As Japanese art, known as Japonisme, appeared and spread in France during the late 1860s, the appeal and attraction of shunga, first to French and later to other European artists was enormous. Artists experimenting with new styles and subjects loved the uninhibited freedom and naturalness with which shunga represented sexual liaisons. The discovery of such prints facilitated a new vision of eroticism and representation of sexuality, which became increasingly visible in the works of many avant garde artists from the 1870s and 1880s onward.

One of the first painters to explore the connection between eroticism and Orientalism was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, especially in his acclaimed images of nude odalisques. His early sketches demonstrate that the anatomical disparity of this odalisque – her leisurely extended body painted in a Mannerist style – was done intentionally in order to intensify the sensuality of a scene reminiscent of the exotic ‘oriental’ realm of harems and concubines.

What was seductive about Japanese erotic imagery was not simply its sensuality, it was also the discovery of a new, more natural, vivid and expressive mode for illustrating the erotic. With their images free of taboo and stratagem, revealing the most intimate and secretive of pleasures, shunga made a powerful impression.

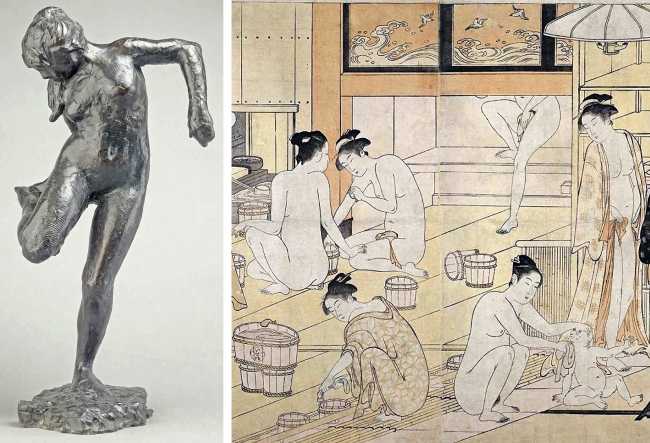

Another artist who was greatly impressed by Japanese art, and who was an avid collector of Japanese prints and books, was the French impressionist Edgar Degas. He was one of the artists who best combined the lessons of Japanese art into his own personal view on the modern world and into his artistic methodology. Many of Degas’s nude and semi-nude women evoke a sense of eroticism in the gestures and positioning of the figures set in scenes of enduring movements which are strikingly close to ukiyo-e prints portraying women bathing.

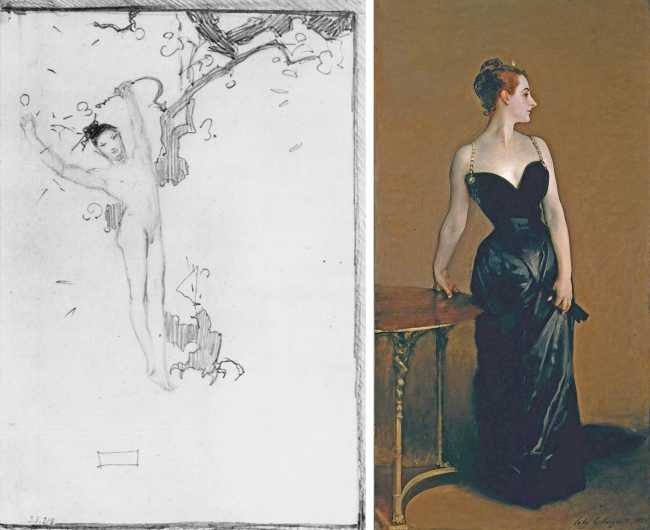

Although it is not quite so easy to link John Singer Sargent’s works directly with the shunga prints that he collected, his drawing ‘Nude Oriental Youth with Apple Blossom’ echoes erotic Japonisme in its depiction of a naked adolescent with a characteristic hairdo of the type worn by Japanese courtesans. The erotic aspect of Sargent’s work is well known, not only through his drawings of masculine nudes in the Album of Nude Studies (c.1890–1915), but also through many of his paintings, such as his ‘Portrait of Madame X’, which caused a public scandal at the time because of its sexual innuendo.

Many artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century were influenced by Japanese shunga art, including Impressionists such as Rodin, Degas and Manet, and artists of the Vienna Secession like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, not to mention Aubrey Beardsley, Edoardo Chiossone, Félicien Rops, and members of the German art movement Die Brücke.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, one of Die Brücke, produced a series of erotic drawings entitled Erotica in which the dialogue between his art and shunga is clearly apparent. Kirchner’s work clearly combines Japonisme and eroticism through the inclusion of Japanese objects and the use of shunga compositions and motifs.

One of the best-known artists influenced by shunga was the passionate Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. Famous for saying that ‘good artists copy, great artists steal’, over the course of his artistic career it is very clear that Picasso’s eyes were opened to the art of Japan, and especially to its erotic prints.

Like Degas, Rodin and Toulouse-Lautrec, Picasso was attracted by the elegant eroticism of shunga prints, in which the composition focuses on the explicit sexual act without losing any of its delicacy in the treatment of faces, clothing or setting. It is surprising that Picasso, whose work is imbued with eroticism, should have collected so few erotic works himself, which gives his shunga prints particular significance.

The work of all these artists emphasise the important role that the arrival of shunga played in the quest for innovation in artistic freedom. By its very nature, shunga’s fresh take on sexuality was recognised as a source of renewed inspiration in belle époque erotic art. However, the discovery of Japanese art and culture by no means ended there – it served as an inspiration and model for the continued exploration of art and aesthetics into the rest of the twentieth century and beyond.