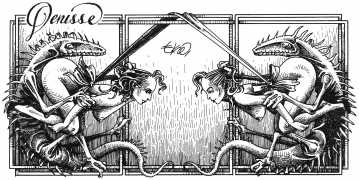

If you are born with a name like Héctor Stanisłao de la Garza Batorski, it isn’t hard to understand the usefulness of creating a short nom d’artiste that people can easily remember, which is why most people know Héctor de la Garza as Eko. Eko is the best-known of a generation of Mexican illustrators and cartoonists born in the 1950s and 60s who use edgy drawings to explore the rich borderlands of eroticism, religion, politics and mortality. Though his work has appeared in Spain, Germany and the USA, he is still largely unknown beyond his native country.

If you are born with a name like Héctor Stanisłao de la Garza Batorski, it isn’t hard to understand the usefulness of creating a short nom d’artiste that people can easily remember, which is why most people know Héctor de la Garza as Eko. Eko is the best-known of a generation of Mexican illustrators and cartoonists born in the 1950s and 60s who use edgy drawings to explore the rich borderlands of eroticism, religion, politics and mortality. Though his work has appeared in Spain, Germany and the USA, he is still largely unknown beyond his native country.

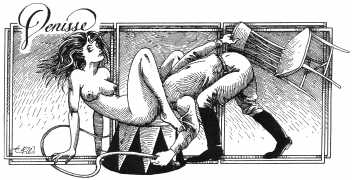

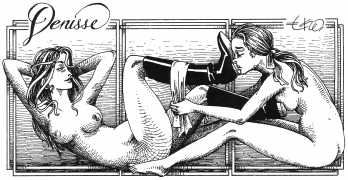

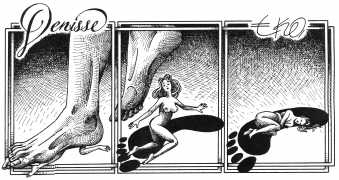

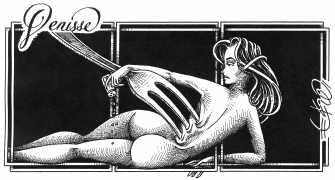

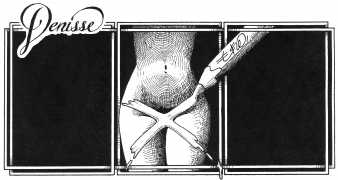

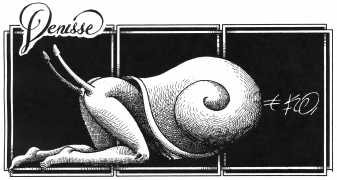

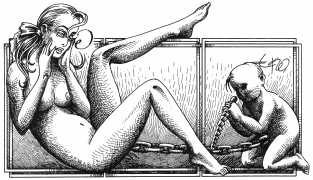

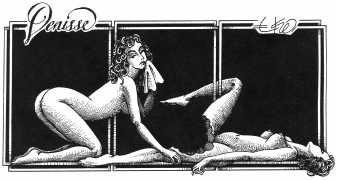

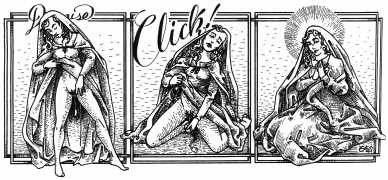

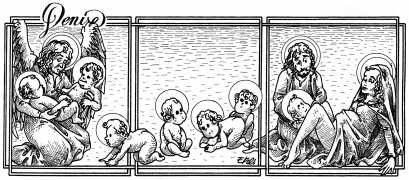

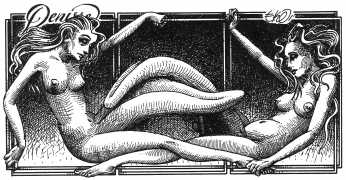

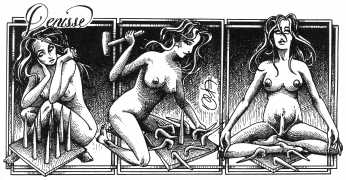

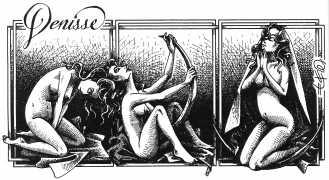

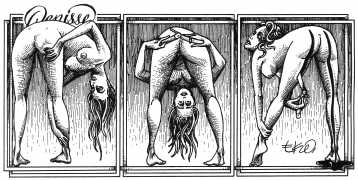

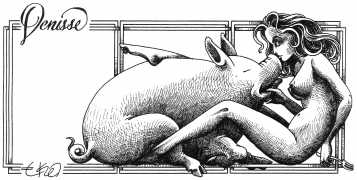

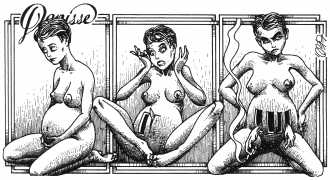

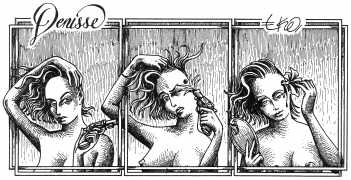

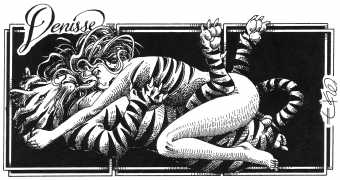

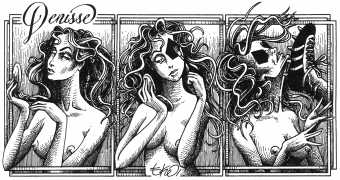

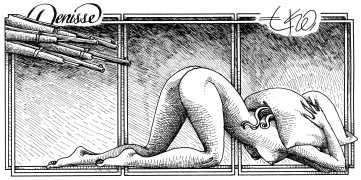

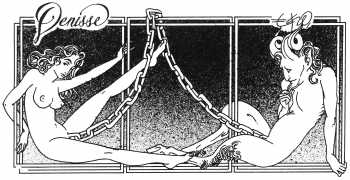

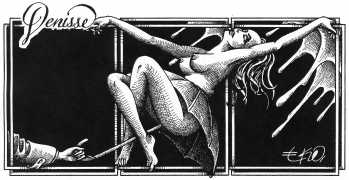

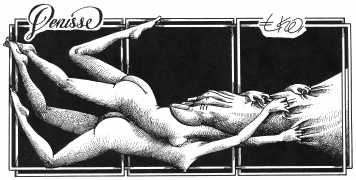

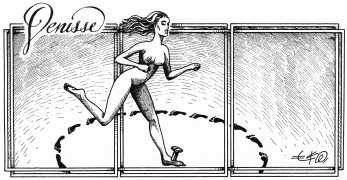

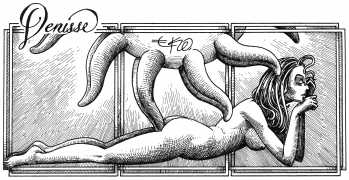

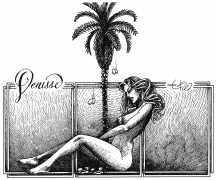

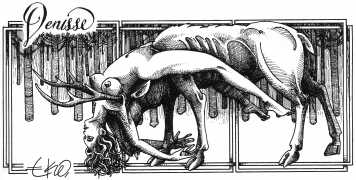

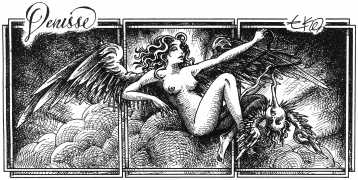

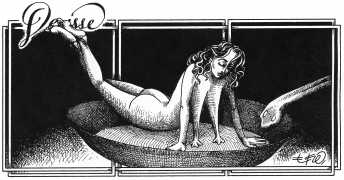

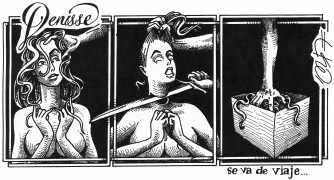

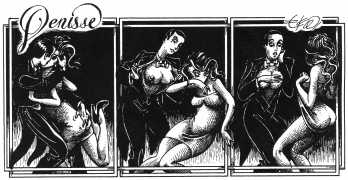

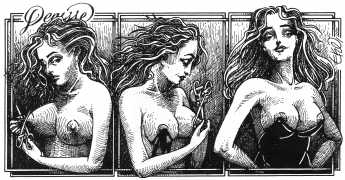

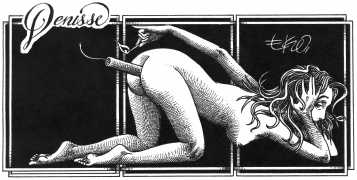

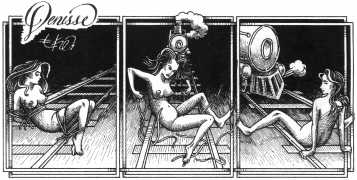

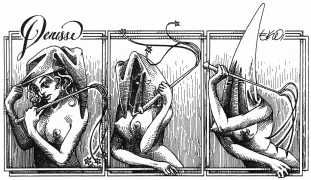

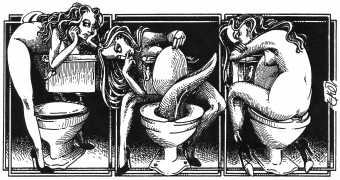

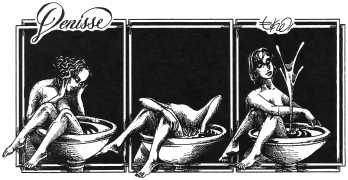

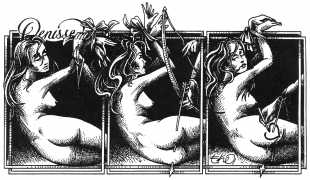

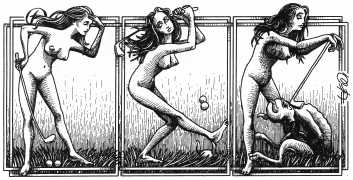

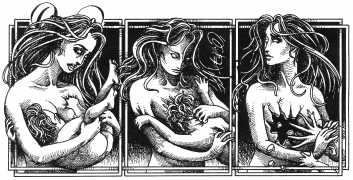

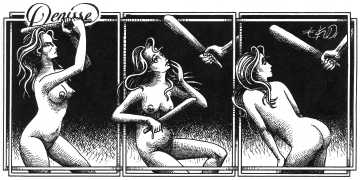

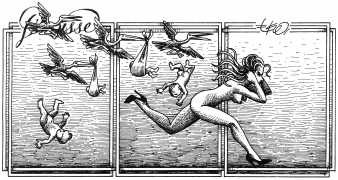

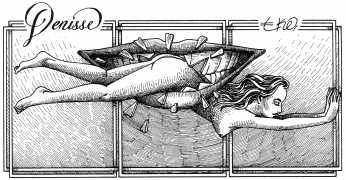

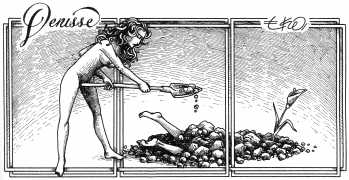

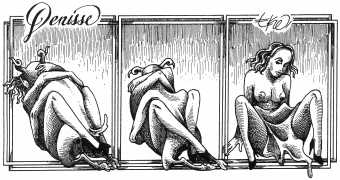

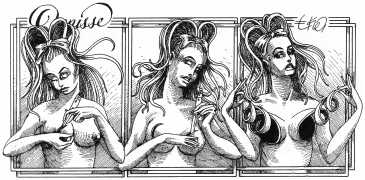

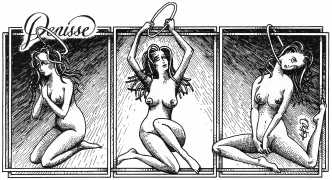

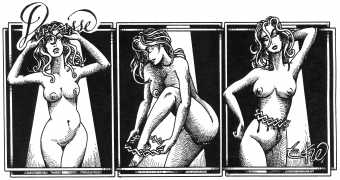

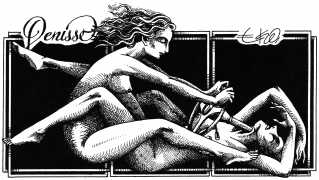

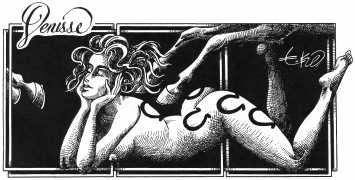

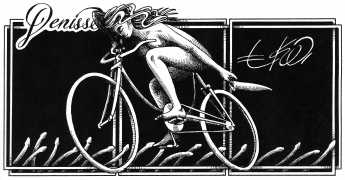

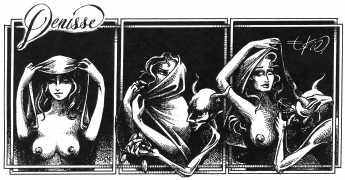

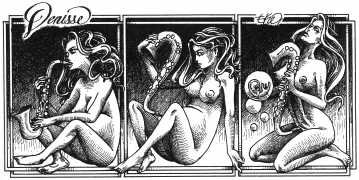

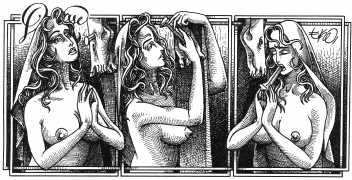

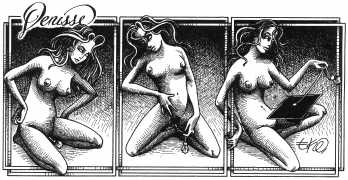

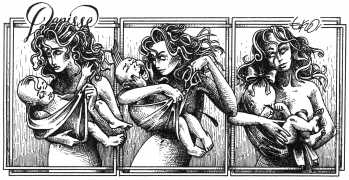

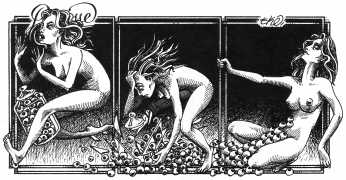

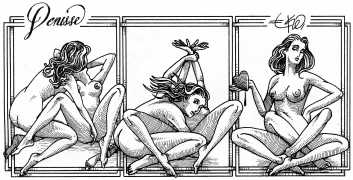

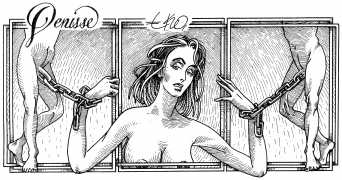

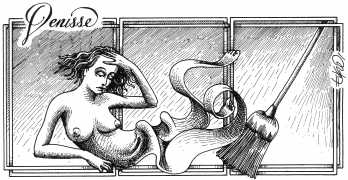

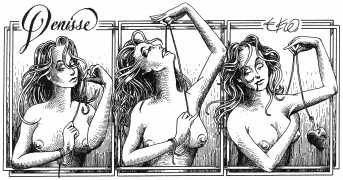

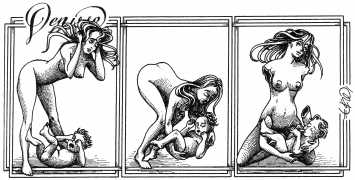

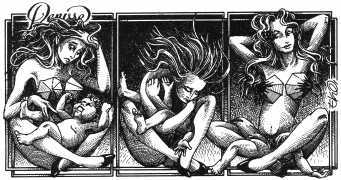

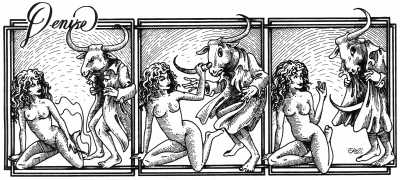

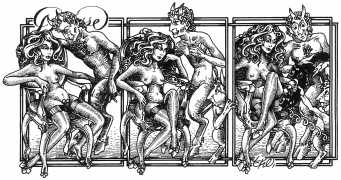

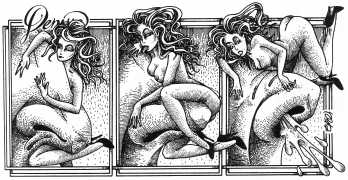

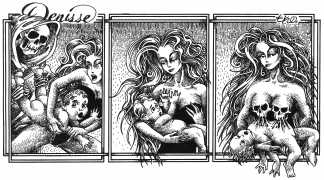

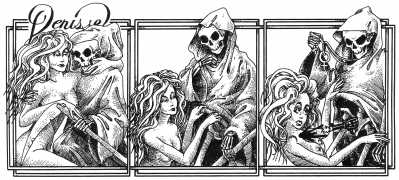

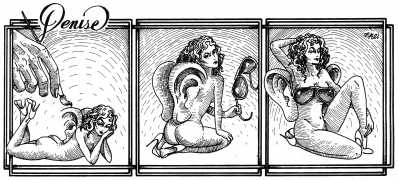

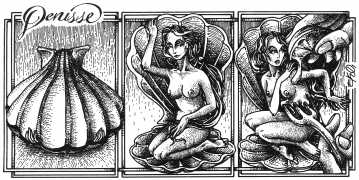

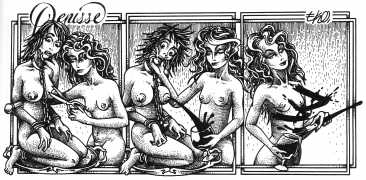

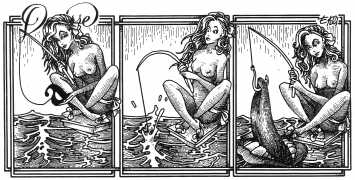

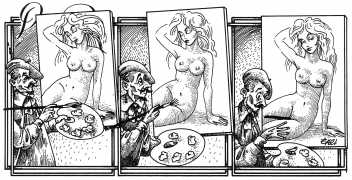

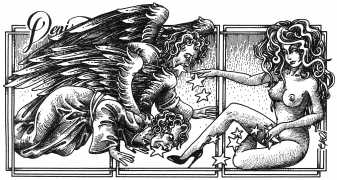

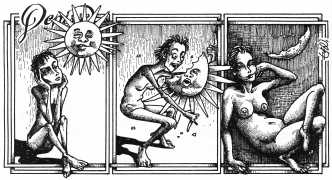

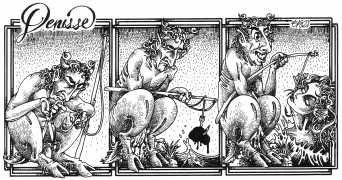

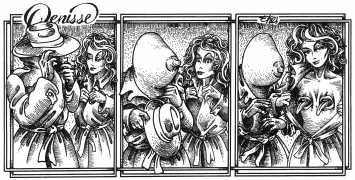

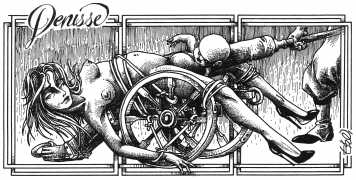

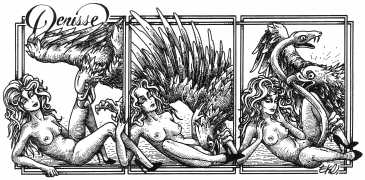

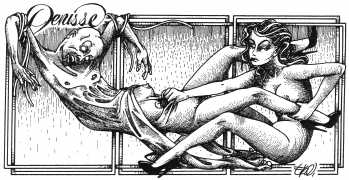

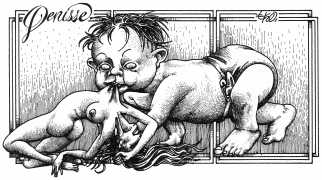

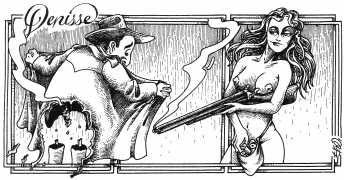

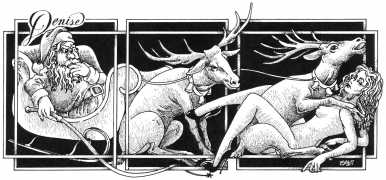

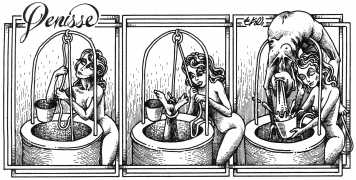

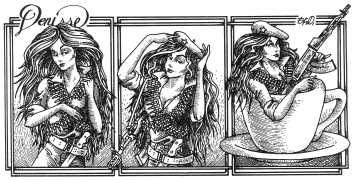

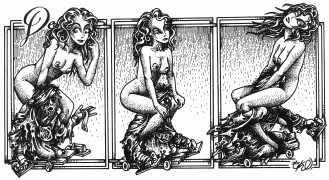

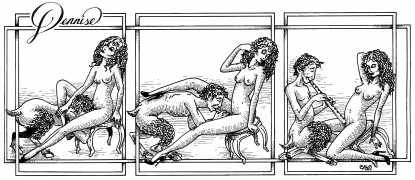

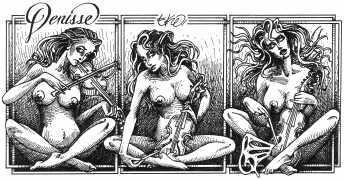

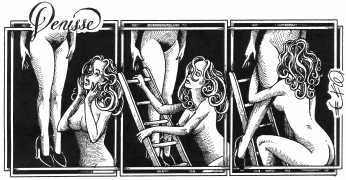

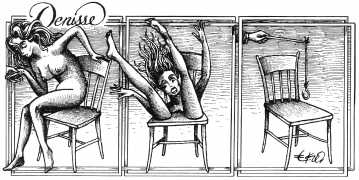

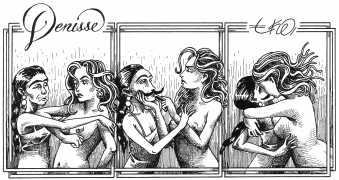

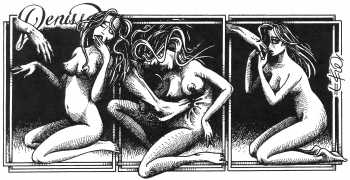

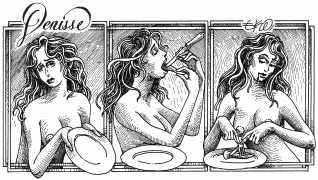

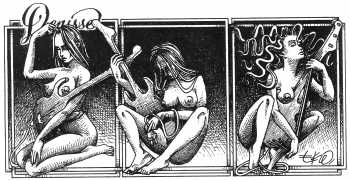

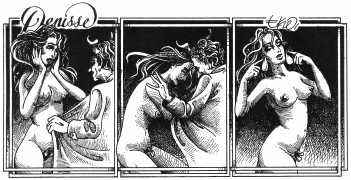

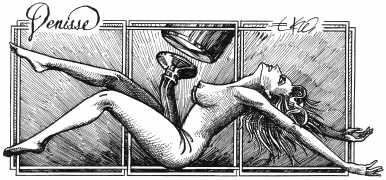

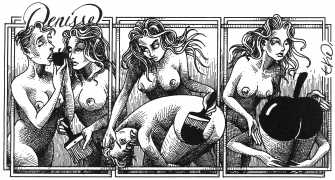

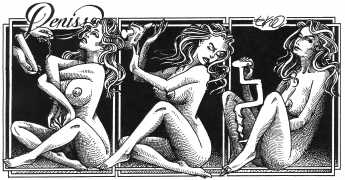

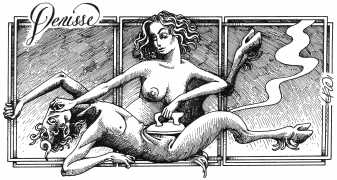

Eko grew up in Monterrey in north-eastern Mexico in an artistic family; early inspirations included Salvador Dali and the Spanish film-maker Luis Buñuel. He studied poster design with Wiktor Górka, and started drawing in his trademark Chinese ink in the early 1980s. In 1985 he met Huberto Batis, the editor of the weekly cultural news magazine Sábado (Saturday), and suggested that his fantasy character Denisse might find a regular slot in it. For several years, first in Sábado and later in other publications, Denisse became Eko’s main channel for commenting on the strange social and moral conventions of the apparently normal world.

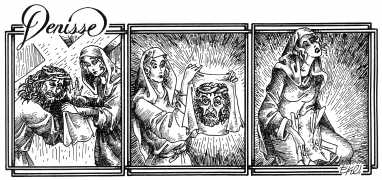

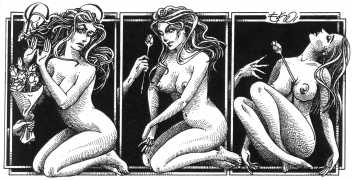

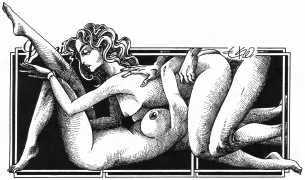

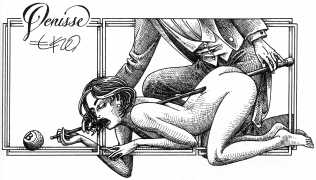

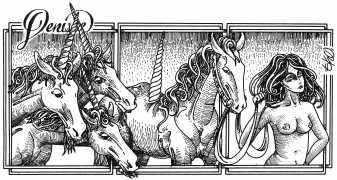

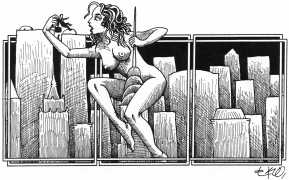

Beyond the world of Denisse, Eko has always looked for opportunities to illustrate important texts, and while he would have loved to be commissioned to produce drawings for erotic classics like Sade and Louÿs, he has instead turned his considerable skills to rather more mainstream titles, including Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, and the graphic novel Pancho Villa toma Zacatecas (Pancho Villa takes Zacatecas, Sexto Pisto, 2013).

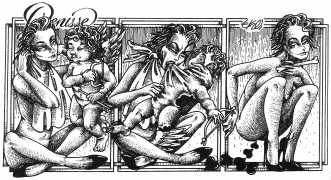

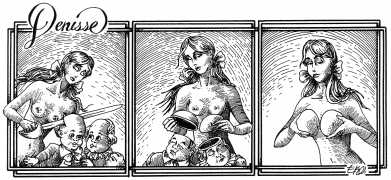

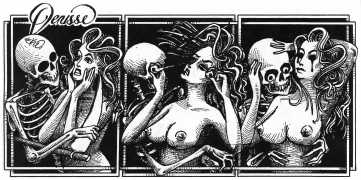

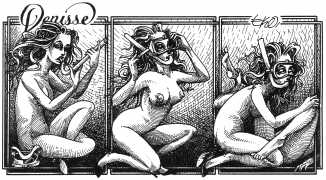

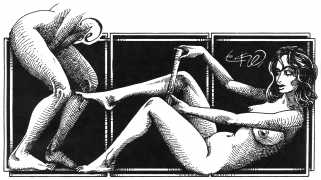

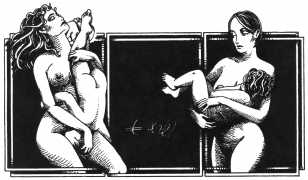

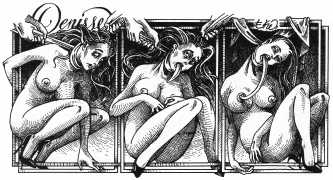

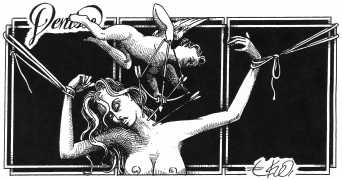

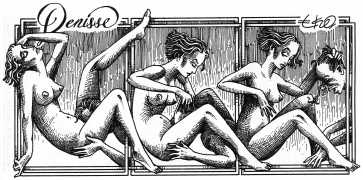

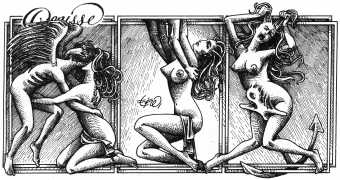

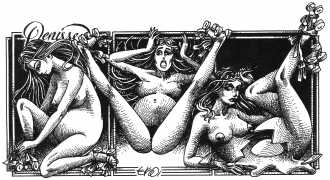

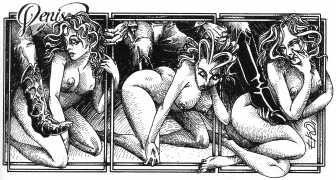

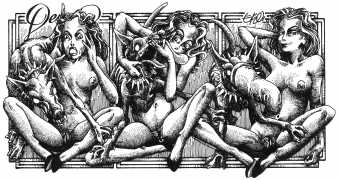

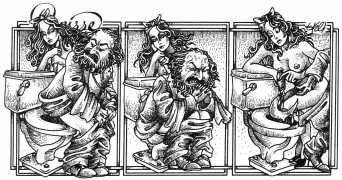

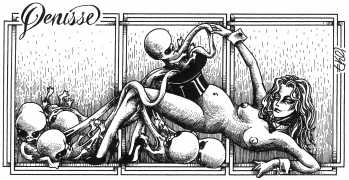

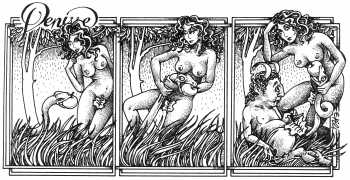

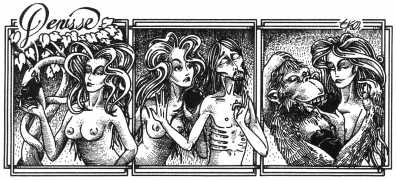

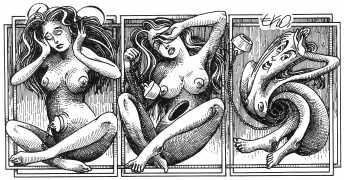

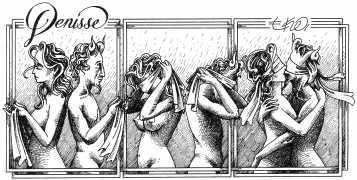

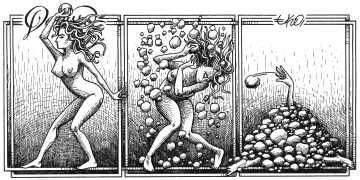

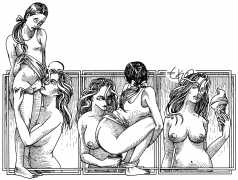

Eko is very aware that his work is transgressive, bordering on the unspeakable and undrawable, which is why he has regularly been censored and his work removed from exhibitions. After an experience in 2009 when several of his drawings were taken down from a show in Mexico City, he wrote ‘I’m aware that many visitors were shocked by the explicit images of penises and pussies hanging on the walls. Yet on the news every day we see torture, murders and beheadings, often committed with impunity, while exploration of the human body and sexuality is considered a crime. Until we are able to look honestly at ourselves we will not be able to face the deeper problems of our culture. I am aware that my work, more than anything, uncovers the prejudices and limitations of society, and I take that risk every time I draw. My work will continue. Censorship is not a force capable of stopping me.’

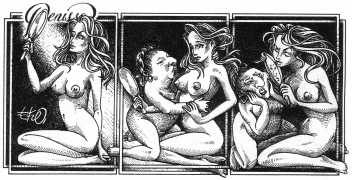

As Armando Pereira, Professor of Hispanic-American Literature at the Universidad de México, writes of Eko, ‘His imagination is populated by ghosts, monsters, creatures that display a tortuous, blasphemous, pornographic eroticism, an eroticism that ventures beyond all norms and routines socially accepted and sanctioned by public morals. Many will be scandalised when they contemplate it – their modesty and prudishness compel them to do so. Others, on the other hand, will find in Eko’s drawings a channel for their own fantasies. I believe that Eko does not seek to scandalise; rather he seeks accomplices, looks for the ghosts that haunt us all – in skin and flesh, ink and paper – in a diverse and plural world in which bodies can fully acknowledge and integrate the imaginary that constitutes them.’

We would like to thank our Russian friend Yuri for suggesting the inclusion of this artist.