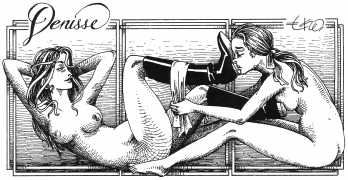

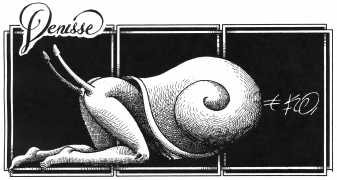

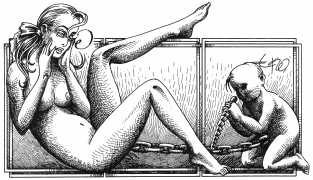

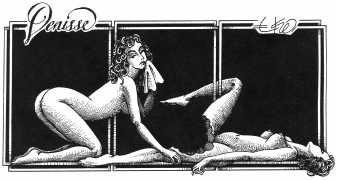

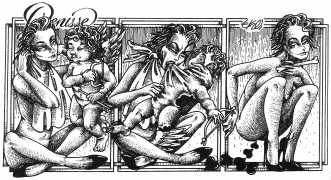

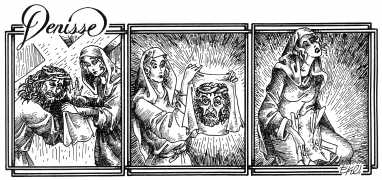

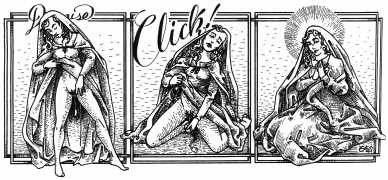

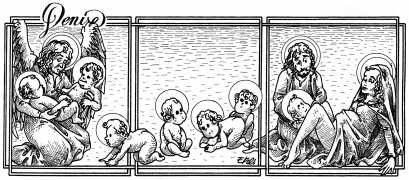

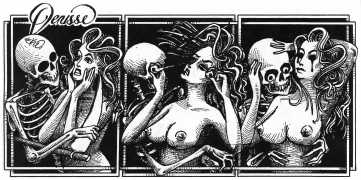

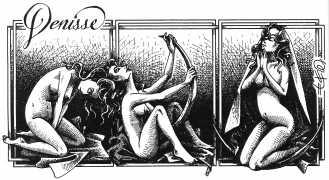

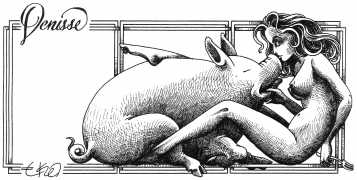

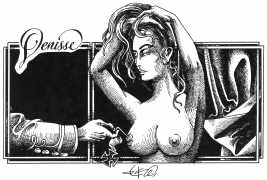

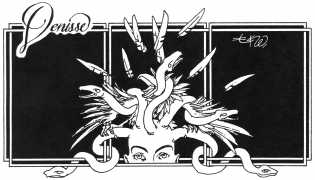

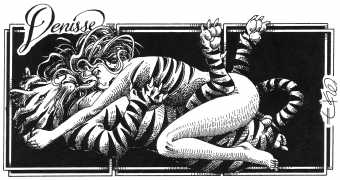

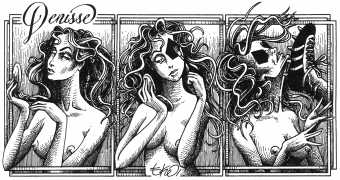

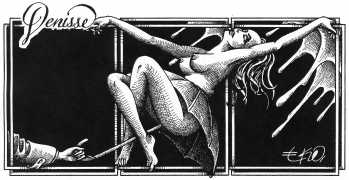

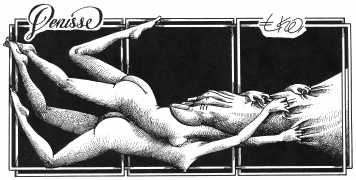

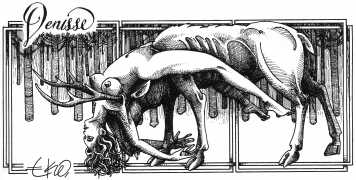

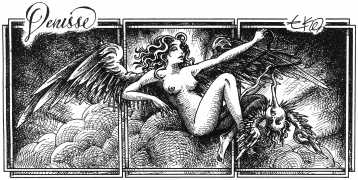

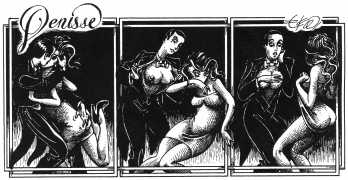

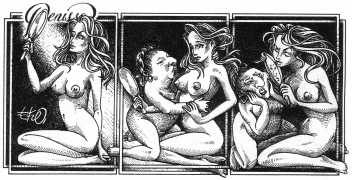

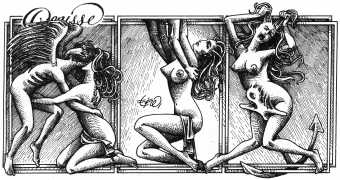

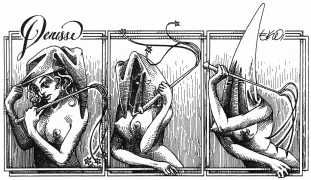

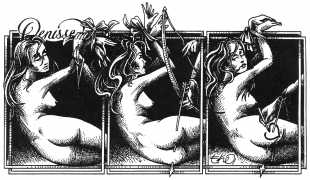

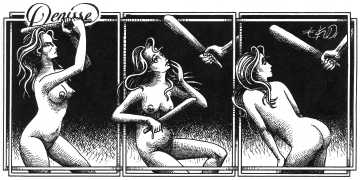

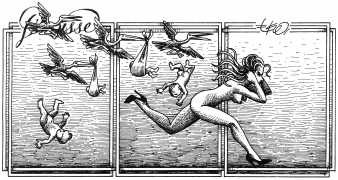

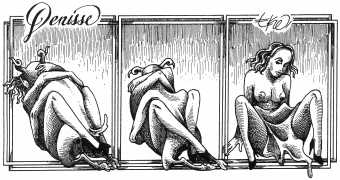

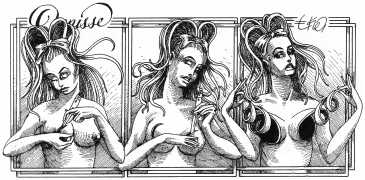

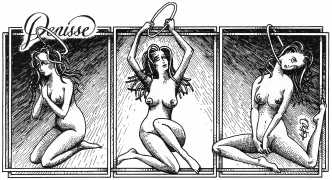

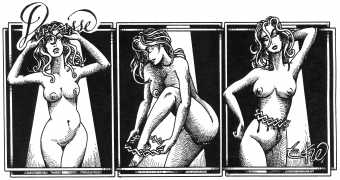

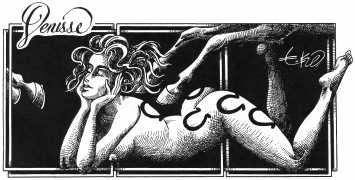

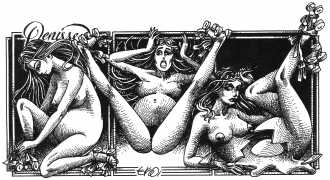

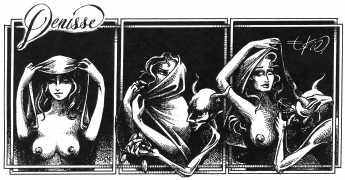

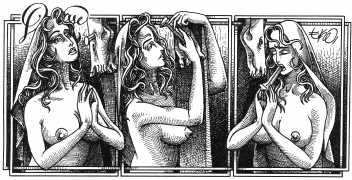

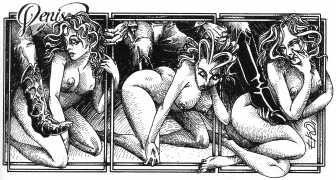

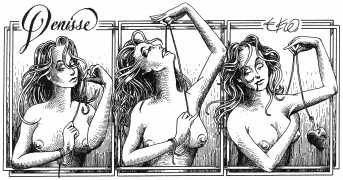

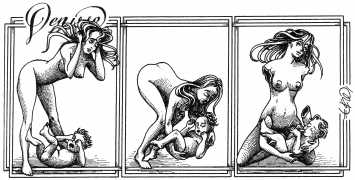

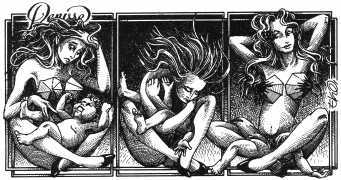

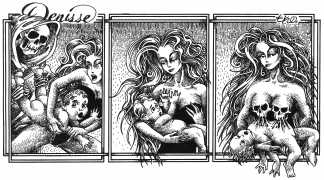

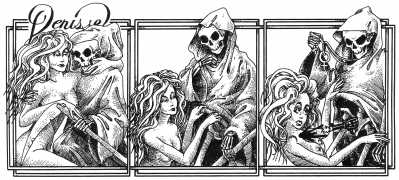

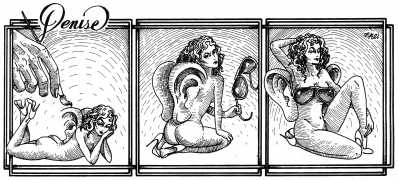

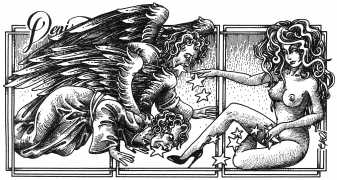

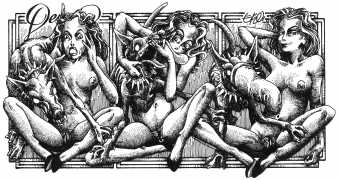

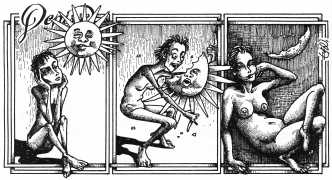

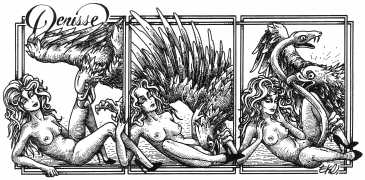

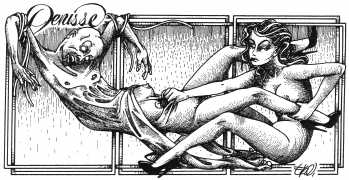

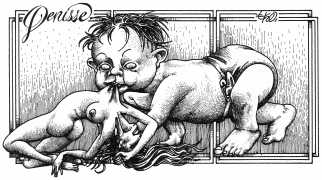

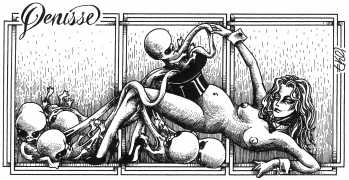

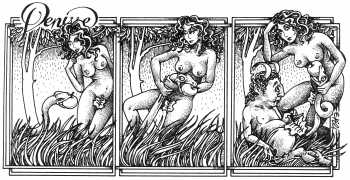

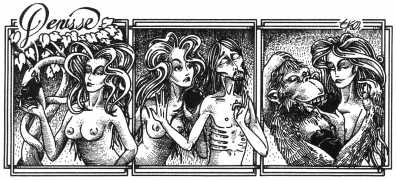

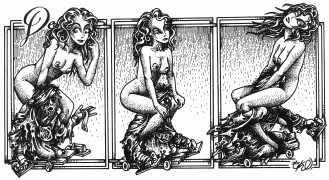

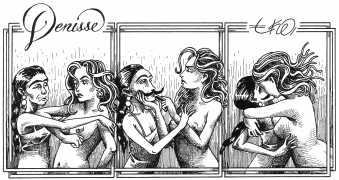

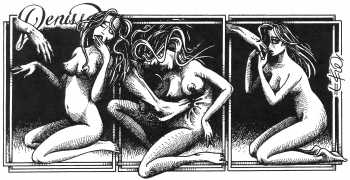

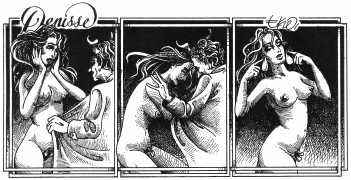

In his introduction to this, the most complete collection of Denisse, the fellow Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas (1934–2017) writes, ‘Denisse fascinates and obsesses me. Denisse’s creator is an exceptional cartoonist, a cultured man who has read the authors of erotic literature, especially the Marquis de Sade, and has studied the works of great artists. Denisse, as Eko himself explained it to me, is the result of his own sexual fantasies. She is not a prostitute; she is a lonely woman of enormous beauty, anguished by her erotic dreams. Her nymphomania leads her to populate her fantasies with skulls and corpses, pain and anguish.’

In his introduction to this, the most complete collection of Denisse, the fellow Mexican artist José Luis Cuevas (1934–2017) writes, ‘Denisse fascinates and obsesses me. Denisse’s creator is an exceptional cartoonist, a cultured man who has read the authors of erotic literature, especially the Marquis de Sade, and has studied the works of great artists. Denisse, as Eko himself explained it to me, is the result of his own sexual fantasies. She is not a prostitute; she is a lonely woman of enormous beauty, anguished by her erotic dreams. Her nymphomania leads her to populate her fantasies with skulls and corpses, pain and anguish.’

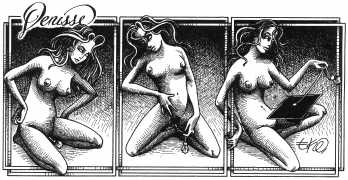

Eko’s Denisse was first collected in book form in 1990 by Editorial Grijalbo; this much expanded edition is published by Minimalia in their Ediciones del Ermitaño series.

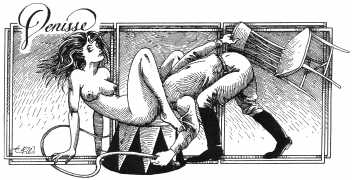

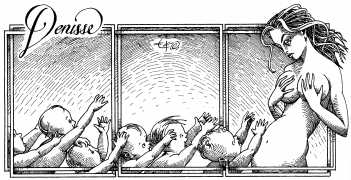

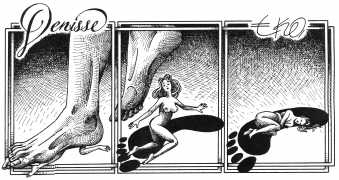

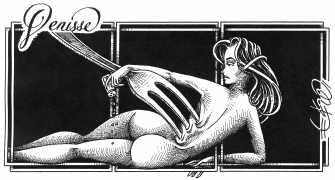

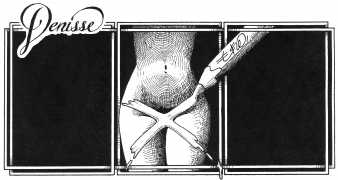

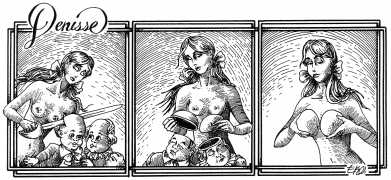

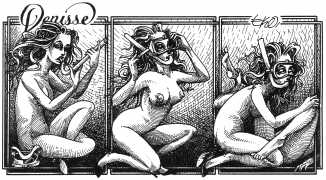

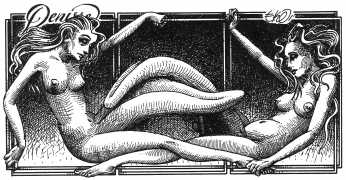

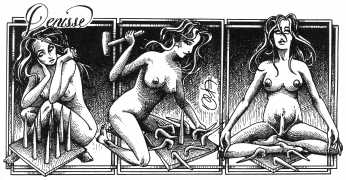

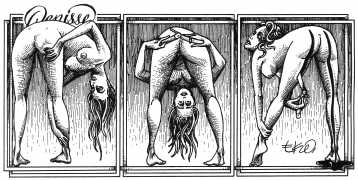

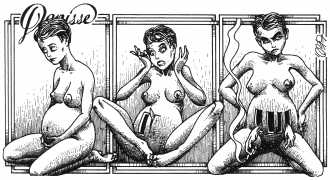

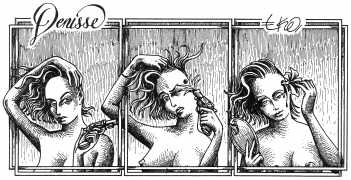

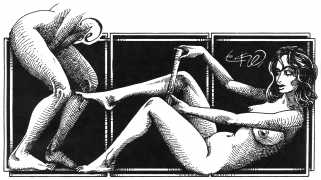

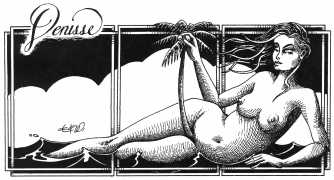

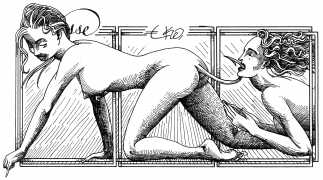

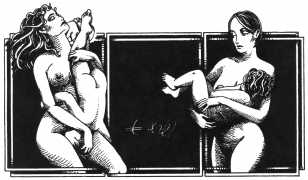

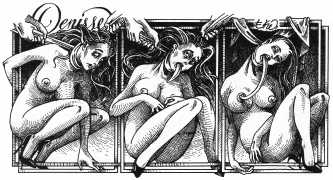

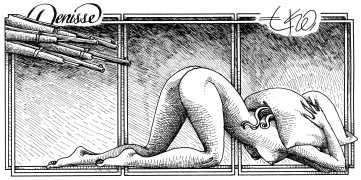

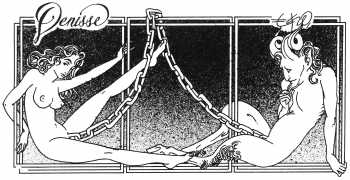

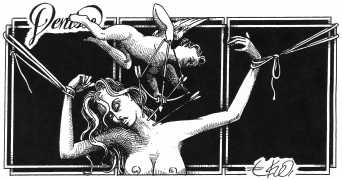

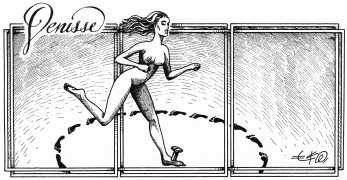

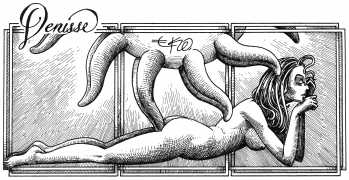

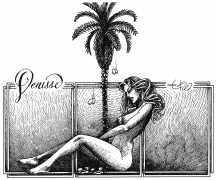

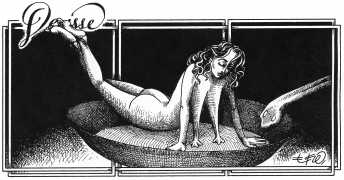

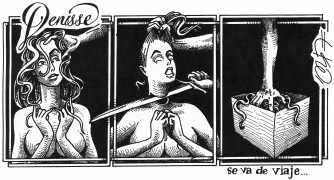

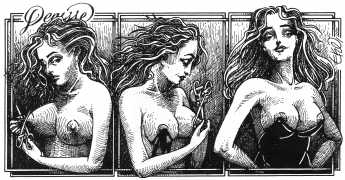

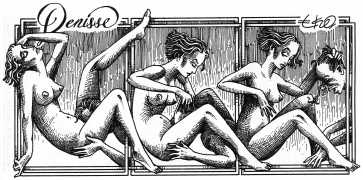

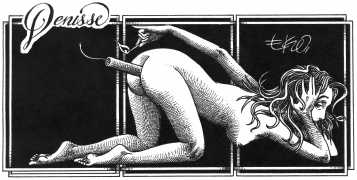

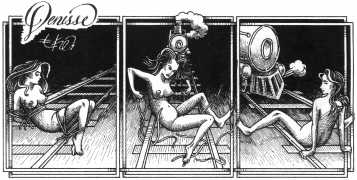

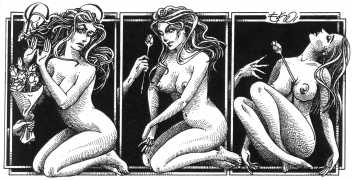

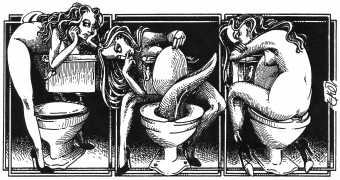

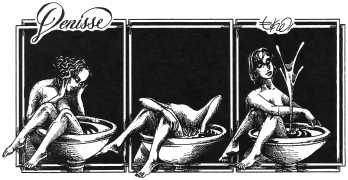

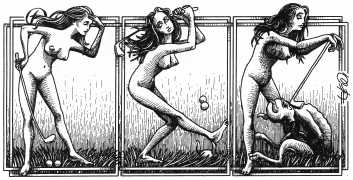

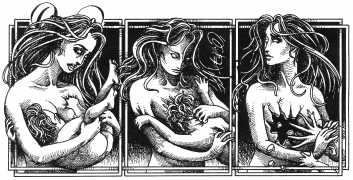

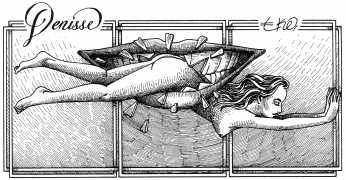

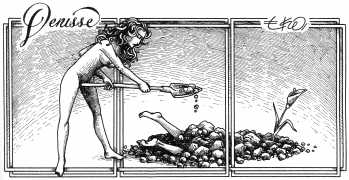

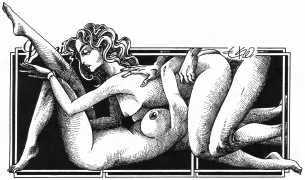

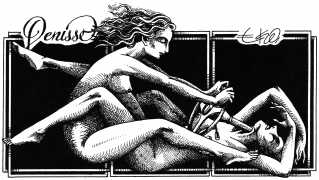

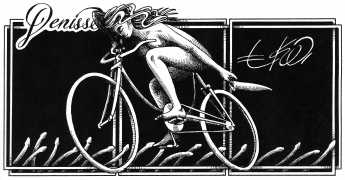

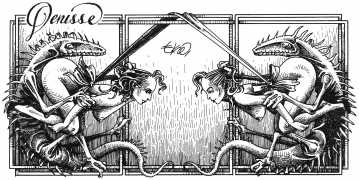

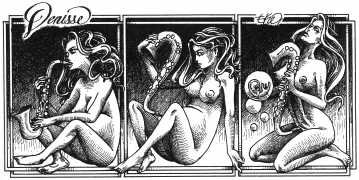

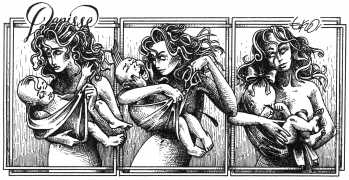

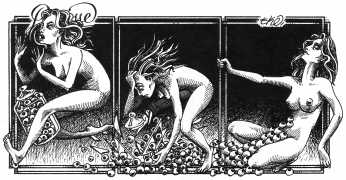

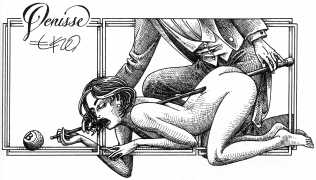

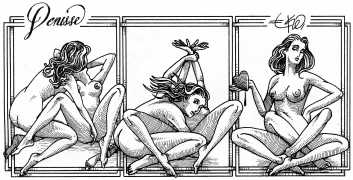

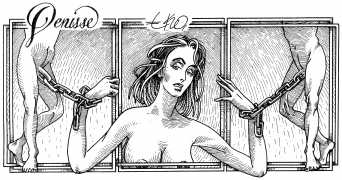

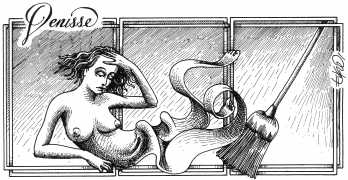

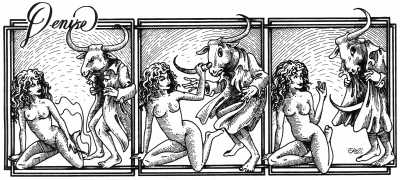

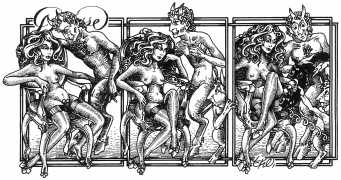

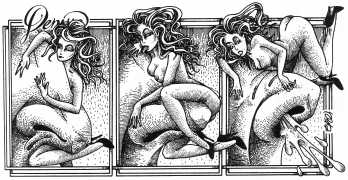

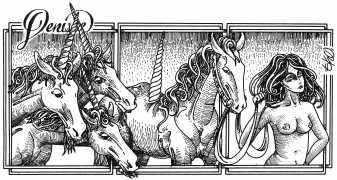

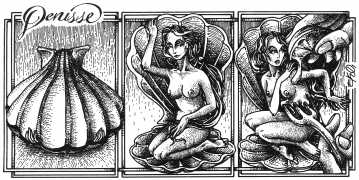

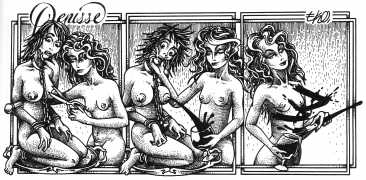

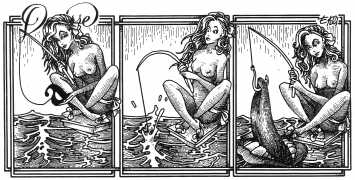

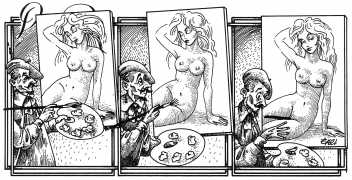

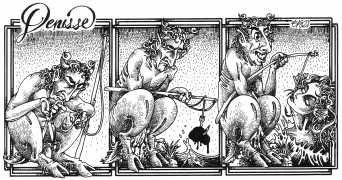

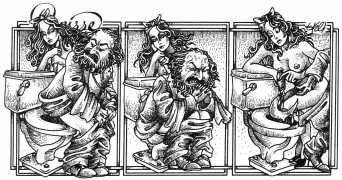

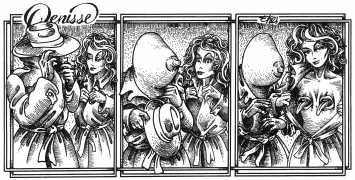

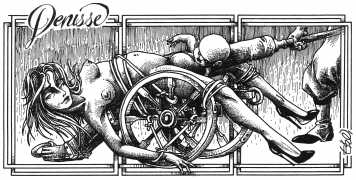

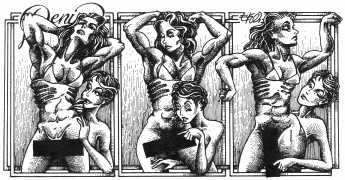

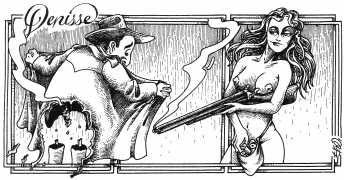

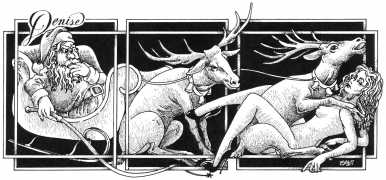

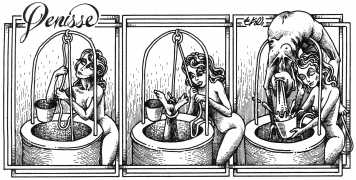

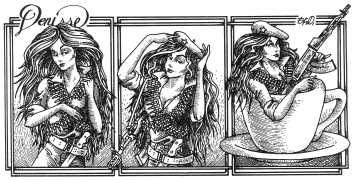

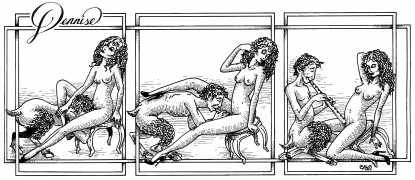

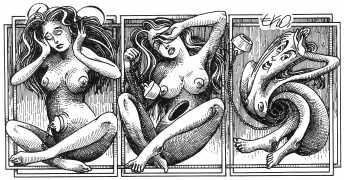

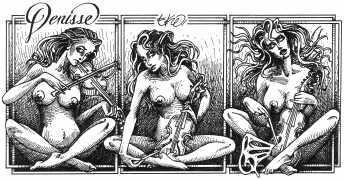

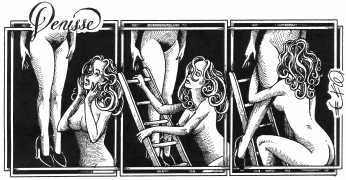

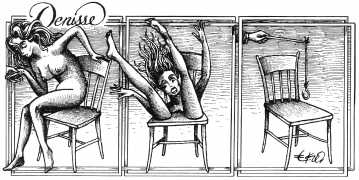

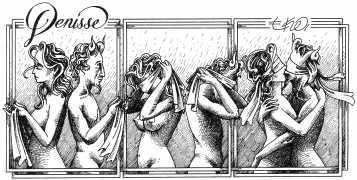

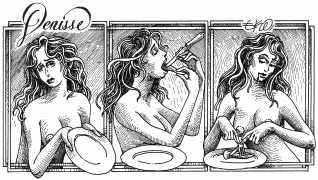

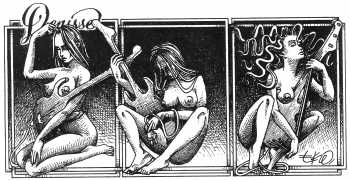

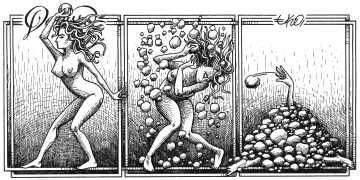

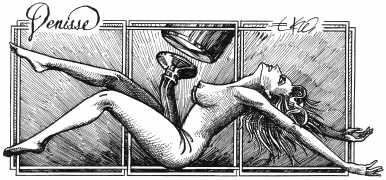

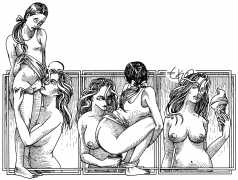

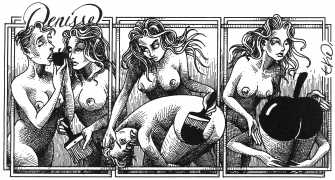

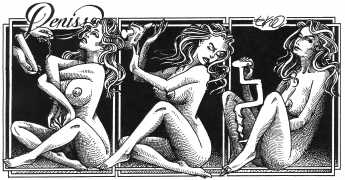

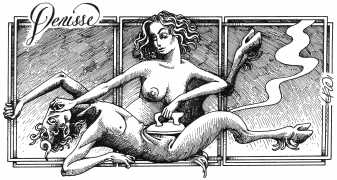

In these 160 graphic mini-narratives we see Denisse, ‘a beautiful woman with wild hair and always more than naked’ as Rogelio Villarreal wrote in 2009 in Milenio Semanal, in almost every conceivable situation a naked woman could find herself in. There really are no holds barred, as Eko incorporates imagery from religion and mythology, de Sade and Bataille, the kitchen and the workshop. Flesh is stretched, warped, even literally screwed in every sense of the word.

Here is Armando Pereira again: ‘Denisse’s naked body is not only surrounded by other bodies, bodies of men and women, satyrs and demons, with which she shares desperate intimacy. It is also accompanied by a whole instrumental universe invoked to increase pleasure – swords, bananas, scissors, toilets, nails, dog collars, whips and screws. These objects in themselves rarely carry a single meaning, often undergoing a metamorphosis in which the phallic object is devoured, where the pain of an incision in the flesh becomes a secret and longed for pleasure, where the material universe deviates from its original purpose and is put at the service of pleasure, where the imaginary initiates scenarios without limits.’