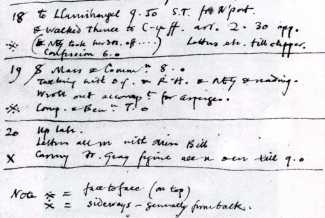

‘An endless curiosity about sex’ is how Eric Gill’s daughter Petra described her father’s rationale for his lifelong search and experimentation in the ways in which people interact intimately with one another. But she only shared her insight long after Gill’s death, and after his careful but thorough biographer Fiona MacCarthy had chosen to tell the world what the sexual codes in his meticulously-recorded diaries revealed.

‘An endless curiosity about sex’ is how Eric Gill’s daughter Petra described her father’s rationale for his lifelong search and experimentation in the ways in which people interact intimately with one another. But she only shared her insight long after Gill’s death, and after his careful but thorough biographer Fiona MacCarthy had chosen to tell the world what the sexual codes in his meticulously-recorded diaries revealed.

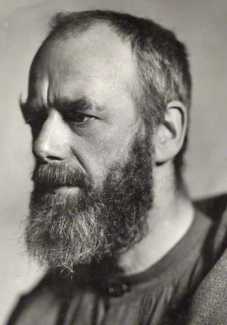

Sculptor, typeface designer, stonecutter and printmaker, intimately associated with the arts and crafts movement, Gill was a deep and controversial thinker who sought throughout his life to live according to his fervently-held views on contemplative religion, artistic integrity and personal freedom, even when – as was so often the case – they contradicted each other. He married when he was just 22, and lived with his wife Ethel (after her conversion to Catholicism known as Mary), three daughters and adopted son in a succession of artistic communities in which the studio, the Catholic chapel and the bedroom all played an essential role.

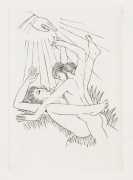

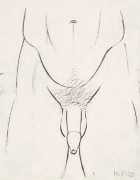

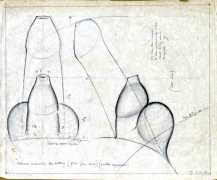

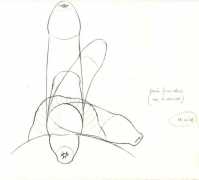

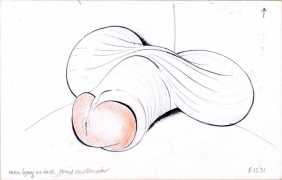

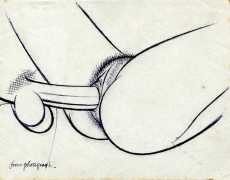

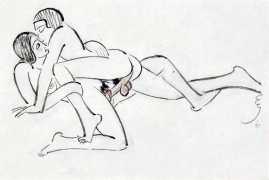

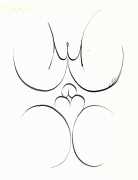

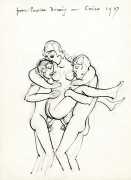

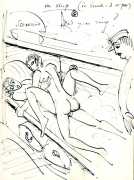

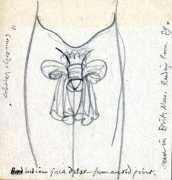

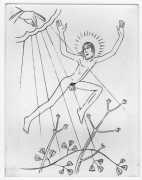

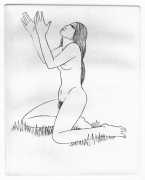

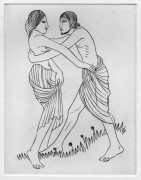

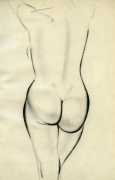

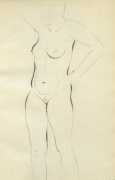

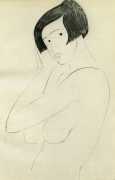

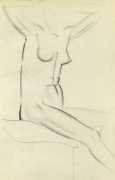

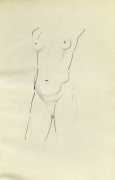

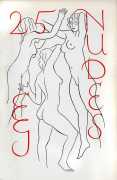

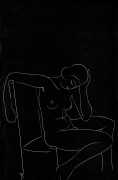

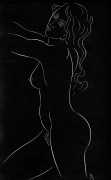

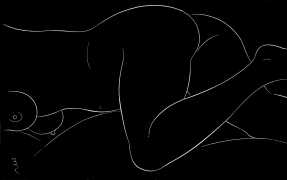

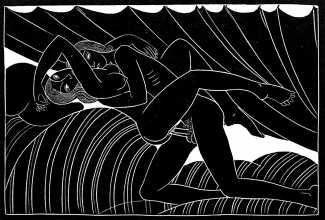

His diaries describe his sexual activity in great detail, including extramarital affairs, incest with his two eldest teenage daughters, incestuous relationships with his sisters, and sexual acts with his dog, all aspects of his life which were little known until publication of Fiona MacCarthy’s biography. His interest in sex, procreation and the life force were ever-present in his art; his nude sculptures had real genitals; his nude prints had real pubic hair.

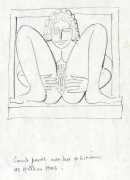

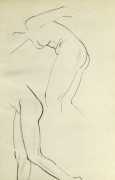

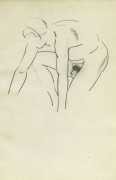

Eric Gill’s life and work is well-documented, especially by his honest and sympathetic biographer Fiona MacCarthy (Eric Gill, Faber, 1989) and by Malcolm Yorke (Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit, Constable, 1981). He was a formidable sculptor and graphic designer, and his timeless typefaces are still in everyday use. His skills, though, were as a designer rather than as an artist; when working in two dimensions on paper his medium was the clean line rather than subtle shading and colour. He had the ability to suggest skin forms and contours with two or three lines, and even though his proportions were sometimes exaggerated and stylised his naked human bodies are entirely believable, his relationship with his models all the more immediate for knowing that he regularly, if inappropriately, crossed the boundary between model and lover.