An experienced art historian and long-time director of London’s famous Tate Gallery, John Rothenstein was well-placed to write an honest assessment of Eric Gill’s early attempts at drawing the nude. A collection of Gill’s studies from the middle part of 1926, when he was living in the small community at Capel-y-ffin in Wales and most actively exploring his own sexuality, had been left to the Tate, and Rothenstein’s introduction, reproduced below in full, explores its significance and the part drawing played in Gill’s artistic development.

An experienced art historian and long-time director of London’s famous Tate Gallery, John Rothenstein was well-placed to write an honest assessment of Eric Gill’s early attempts at drawing the nude. A collection of Gill’s studies from the middle part of 1926, when he was living in the small community at Capel-y-ffin in Wales and most actively exploring his own sexuality, had been left to the Tate, and Rothenstein’s introduction, reproduced below in full, explores its significance and the part drawing played in Gill’s artistic development.

First Nudes was published in 1954 by Neville Spearman.

INTRODUCTION

Eric Gill was one of those exceptional beings who try to live their lives in accordance with their intellectual convictions. Most of us accept, as an inevitable part of the universal scheme of things, the wide gulf between such convictions as to what is right and our tendency to disregard them in practice. Like all other men, he fell short, often, of the standards he set himself, but he made an attempt to live according to an elaborately worked out plan.

One of his convictions was that making – he disliked the term art as implying a false distinction between making a painting or a piece of sculpture and making any other object – is primarily a product of imagination. He rejected the concept of art as direct imitation of nature and he disapproved, in con-sequence, of the idea that ‘the study of nature and particularly of the human body and its anatomy are the first necessities of the serious art student’.

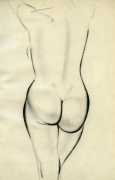

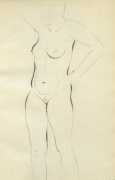

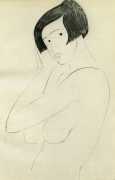

Gill was, however, deeply interested in his fellow human beings and he was – and gloried in being – a sensual man. The time came, therefore, when he made a series of careful drawings from the naked model. The time was May–June, 1926. The subjects, we may be sure, were not professional models, of the use of which he disapproved. ‘What is wrong,’ he once asked, ‘with your friends and relations?’ (I remember his showing me a drawing of a nude girl, made three or four years later than those reproduced here, with a body of breath-taking beauty. To my frivolous question whether he had persuaded one of Mr Cochran’s Young Ladies to pose for him he replied with a touch of severity, ‘Certainly not – she is the librarian at … ’ and named a neighbouring town). These drawings, although most of them are slight, I have described as careful, for there was nothing of the sketcher in Gill: ‘Drawings are ends, not means, and even studies and sketches should be thought of as worth doing for themselves’.

In 1926 Gill had reached the age of forty-four, which is very late for a sculptor or an engraver of figure subjects to begin drawing from life. But this is an example of the consistency of his practice with his ideas. ‘Drawing from life properly comes late in life rather than early. For the training of imagination is the first thing to be seen to, and that is best achieved by life and experience; and in order to make this particular thing, this construction of lines derived from the sight of human limbs and bodies, the artist is more dependent upon his life and experience than he is in any other business.’ It properly comes late too ‘when the experience of living has filled the mind and given a deeper, a more sensual as well as a more spiritual meaning to material things’.

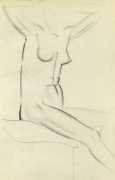

It must be admitted that the drawings reproduced here are of greater interest as the first drawings made from the naked model by a mature artist than impressive in themselves. Regarded simply as drawings from the life they are less accomplished than numbers produced each year in art schools: they are inferior to these, that is to say, as descriptions of their subjects. Gill had no training in drawing from the life, but, what was an equal disadvantage, his ideas stood between him and his subjects. ‘It is what is in your head that matters most and not what the model has in his or her body.’ What Gill had in his mind when he was making the sixth drawing was not the woman seated before him, but a preconceived notion, with a remote kinship to cubism, of what a naked woman ought to look like. The light falls from no particular direction; nothing is observed, least of all the joints, neither wrists, elbows, shoulders nor knees exist. But in other drawings, notably the first, his interest in the model was lively and direct enough to make him forgetful of preconceptions and enable him to note down the form and gesture of the model with exemplary freshness.

In one respect these life drawings of Gill’s are unique, so far as my own experience goes, among drawings by sculptors. The primary preoccupation of sculptors being with solid form, emphasis on volume is usually a characteristic of their drawings. But even as a sculptor Gill was singularly lacking in feeling for solid form. It is therefore after all scarcely to be wondered at, surprising though it may be in other respects, that many of his drawn figures are hardly more than two-dimensional representations.

If I have written critically of these drawings, it should be apparent that I have done so because, both by his outlook and by his want of early training, Gill was unfitted for the direct drawing of the naked model. Such drawings are the very last manifestation of the art by which his achievement should be judged. They afford intimations, nevertheless, of qualities that shine brightly elsewhere: an apprehension of form that can be noble in its clear-cut clarity, a candid and gay if slightly obsessive sensuality, an elegantly workmanlike understanding of the quality of the materials that he used (it is his woodcuts that I more especially have in mind), and a style that reflects the sharp-edged integrity of the man himself.