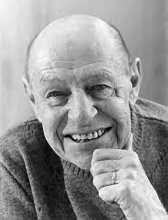

The French artist and self-styled enfant terrible grew up in Le Havre on the north French coast, and in 1918 moved to Paris to study art. However, he gave up his course in painting at the Académie Julian after six months and started working on his own. He knew the painters Raoul Dufy and Fernand Léger, both of whom influenced on his otherwise self-taught approach to art. By 1924 he had given up painting entirely, and ran a wine business for several years, but in 1933 he started painting again, producing mainly puppets and masks. It was only in 1942 that he finally devoted himself to being an artist, or at least to experimenting with different art forms and media.

The French artist and self-styled enfant terrible grew up in Le Havre on the north French coast, and in 1918 moved to Paris to study art. However, he gave up his course in painting at the Académie Julian after six months and started working on his own. He knew the painters Raoul Dufy and Fernand Léger, both of whom influenced on his otherwise self-taught approach to art. By 1924 he had given up painting entirely, and ran a wine business for several years, but in 1933 he started painting again, producing mainly puppets and masks. It was only in 1942 that he finally devoted himself to being an artist, or at least to experimenting with different art forms and media.

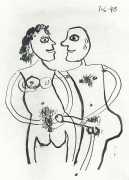

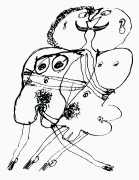

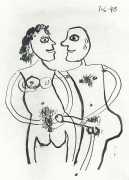

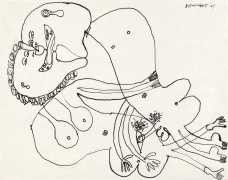

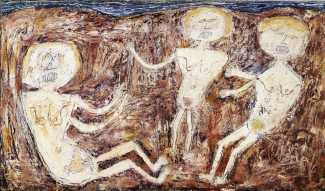

Dubuffet’s return to art was accompanied by a passion for primitive and naive art forms, as well as for paintings made by the psychologically disturbed. By 1945 he had started to collect so called Art Brut (‘raw art’), and in 1948 he founded a society, La Compagnie de l’Art Brut, to promote this type of work. He also wrote some important statements criticising the cultural aims of Western art, advocating a more spontaneous, non-verbal, and spiritually potent qualities of primitive cultural expression. This resulted in a totemic approach to image making which soon revealed itself in his first exhibition, where city life and images of men and women were presented with an aggressively simple and childish vigour. The paintings from this period often look like graffiti or tribal emblems. This is also the period when he produced a number of drawings featuring raw sex, which many viewers saw as crude and childish.

The driving force behind these early works was Dubuffet’s novel and extraordinary painting technique. He combined almost any element with the paint surface, including cement, tar, gravel, leaves, silver foil, dust, and even butterfly wings. In defence of this technique he wrote that ‘art should be born from its raw materials, and spiritually should borrow its language from it. Each material has its own language, so there is no need to make it serve a preconceived language.’ This approach drew him into the field of sculpture, using materials often gathered from beside Parisian railway lines; by the 1970s he was creating enormous architectural environments in concrete. Towards the end of his enormously productive life he involved himself in multimedia projects involving, music, theatre, and his ‘sculpture-habitations’ like Tour aux Figures, Jardin d’Hiver, and Villa Falbala, in which people could sit, wander and contemplate.

For anyone interested in the life, work and ideas of Jean Dubuffet, the Fondation Jean Dubuffet has a comprehensive website here, with a biography and many examples of his work.