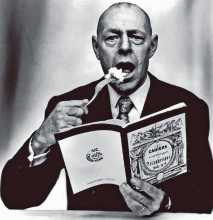

In 1958 Jean Dubuffet posed for an unusual photographic portrait. Not at work painting in his studio, he is seated at a table in formal attire, apparently literally ‘consuming’ a book. Surely one of the most unusual self-representations by a modern artist, this image encapsulates Dubuffet’s lifelong appetite for books.

In 1958 Jean Dubuffet posed for an unusual photographic portrait. Not at work painting in his studio, he is seated at a table in formal attire, apparently literally ‘consuming’ a book. Surely one of the most unusual self-representations by a modern artist, this image encapsulates Dubuffet’s lifelong appetite for books.

Between 1948 and 1950, Dubuffet and four other members of the Compagnie de l’Art Brut put out a number of small books that took, as he put it, ‘le contre-pied des rites bibliophiliques’ (the precise opposite of bibliographic tradition). He set up a ‘petite imprimerie brute’ to produce small hand-made books which he described as ‘Tout à l’opposé de solennités glaçantes que donnent aux éditions de luxe les épais et coûteux papiers, les typographies de grande maison, les amples marges et la profusion des gardes et pages blanches, ils étaient tirés fort modestement à l’aide de dispositifs dérisoires dans un petit format et sur un papier à journal de la plus vulgaire sorte.’ (The complete opposite of the chilling solemnity of luxury editions from prestigious publishers with their thick and expensive papers, their beautiful typography, wide margins and profusion of tissue guards and blank pages, they are drawn very modestly on ridiculous devices, in a small format and on paper of the most everyday kind.) These handmade books were intended as a critique of the very idea of the traditional livre d’artiste.

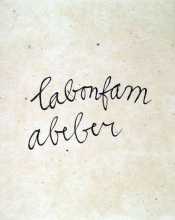

With La bonfam, Dubuffet took the concept to the extreme on several fronts. The handwritten text of the tiny 36-page booklet printed on tracing paper is in phonetic jargon, not instantly recognisable until spoken out loud, so that labonfam abeber par inbo nom becomes La bonne femme à Bébert, par un beau nom (Bebert’s Good Woman, by a Good Name). Dubuffet used this technique in some of his other writings of the time, deliberately forcing the reader not to make assumptions about the ‘correctness’ of language.

With La bonfam, Dubuffet took the concept to the extreme on several fronts. The handwritten text of the tiny 36-page booklet printed on tracing paper is in phonetic jargon, not instantly recognisable until spoken out loud, so that labonfam abeber par inbo nom becomes La bonne femme à Bébert, par un beau nom (Bebert’s Good Woman, by a Good Name). Dubuffet used this technique in some of his other writings of the time, deliberately forcing the reader not to make assumptions about the ‘correctness’ of language.

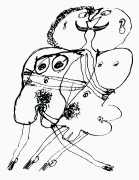

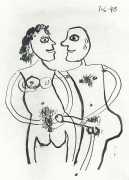

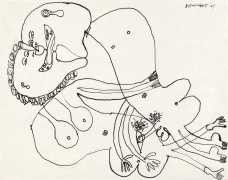

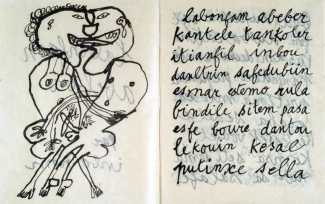

More immediately shocking, however, at least to its 1950 readership, was his blatant sexual imagery. For years Dubuffet’s work had been compared to mud, dirt, and excrement, but this is the only really ‘dirty’ book he made, along with a number of related drawings, and it is quite possible that he made both book and drawings to prove that he could be as explicitly ‘dirty’ as his critics regularly suggested.

More immediately shocking, however, at least to its 1950 readership, was his blatant sexual imagery. For years Dubuffet’s work had been compared to mud, dirt, and excrement, but this is the only really ‘dirty’ book he made, along with a number of related drawings, and it is quite possible that he made both book and drawings to prove that he could be as explicitly ‘dirty’ as his critics regularly suggested.

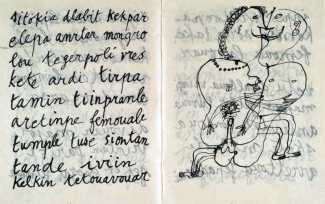

As the art critic Rachel Perry has written, ‘Above all, La bonfam abeber is a conjugaison, a sexual union, that brings together text and image, written and spoken word, in a troubled marriage. Reading is frustrated; the paper so thin and flimsy that you can see right through it, so that the racy images make it hard to read the text. The book is a lesson in distraction, using techniques of interference that slow reading down, disrupt communication, clog the flow of information. Instead of being automatic or transparent, reading is grounded in the body. Playfully poking fun at the seriousness of pornographic books such as Bataille’s, Dubuffet wants us to be turned on by sensory form and experience. He offers an erotics of art that is less about titillation than a call to push back against conventional interpretation and recover our senses.’

As the art critic Rachel Perry has written, ‘Above all, La bonfam abeber is a conjugaison, a sexual union, that brings together text and image, written and spoken word, in a troubled marriage. Reading is frustrated; the paper so thin and flimsy that you can see right through it, so that the racy images make it hard to read the text. The book is a lesson in distraction, using techniques of interference that slow reading down, disrupt communication, clog the flow of information. Instead of being automatic or transparent, reading is grounded in the body. Playfully poking fun at the seriousness of pornographic books such as Bataille’s, Dubuffet wants us to be turned on by sensory form and experience. He offers an erotics of art that is less about titillation than a call to push back against conventional interpretation and recover our senses.’

La bonfam abeber was produced in a limited edition of fifty copies.

As well as the images from the self-published booklet, we have included a set of four related and dated drawings from the collection of Hans-Jürgen Döpp and a couple of others from museum collections including MOMA in New York.