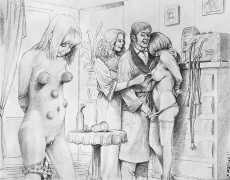

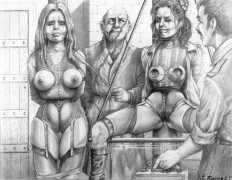

The sado-masochistic work of Joseph Farrel probably raises more issues about the appropriateness of including him in an ‘honest erotica’ resource than almost any other artist, and it is not without misgivings that we have chosen to include him.

Farrel’s biographer and champion Christophe Bier probably makes the argument for inclusion the most persuasively: ‘Modern societies are obsessed with control: control of individuals, ideas, regulations, zero risk worship, politically correct ideology. We are losing the sense of the unexpected, of adventure, of danger. Artists have a decisive political role to play in fighting this ideology, and Farrel’s independence shows the way. By never having been afraid of his fantasies, he expresses his absolute faith in the imagination. Joseph Farrel’s painful dark drawings touch on poetry and dreams. Ultimately they do us good.’

It is with this understanding that we invite you to explore Farrel’s work, but don’t say that you haven’t been warned. He will question and stretch your critical faculties as well as your extreme fantasies, and if you think ‘kink’ is or might be your thing, he will leave you wondering where your boundaries are.

Joseph Farrel has always been drawing. ‘I was drawing naked women at seven,’ he says. ‘I would hide scraps of paper under my bed.’ In 1952 at the age of eighteen, in Oran, when accompanying his father, a construction engineer, he enrolled at the Beaux-Arts, but he only stayed for a month. ‘The teachers felt they had nothing to teach me,’ he explains.

When asked about his influences, he doesn’t mention illustrators. He is first and foremost a reader of clandestine pornographic novels. He has kept, like a precious relic, the photocopies of Les genêts d’or (The Golden Broom), a hard-core text by Pierre Goetz under the pseudonym of Johan Spechter, sold under the counter in the early sixties. Farrel also mentions Jean Vergerie, a literary madman to whom we owe the most bloody novels of the 1930s – Le couvent des tortures (The Convent of Tortures), Goules et vampires (Ghouls and Vampires), and La clinique des cauchemars (The Clinic of Nightmares), all uninterrupted tales of sadism, lacerated and shredded flesh.

Obèis! sinon (Obey or Else!) in 1977 clearly marks the birth of ‘Jo Farrel’, but the artist had already published under another pseudonym, Angelo, illustrating the two volumes of Nuits de Chine with around a hundred ink drawings, not clandestinely published by Eric Losfeld as some claim, but by Librairie Vermeulen. As Farrel explains, ‘A guy introduced me to Mrs Vermeulen, who ran a bookstore in Pigalle. She gave me a manuscript written in blue ballpoint pen. It was written by a woman, I never knew her name. I was twenty-five and broke, with nowhere to live. I found a building near the Chaussée d’Antin where I would settle down at night, in a corridor on the top floor, and draw on little scraps of paper the erotic scenes inspired by the text.’

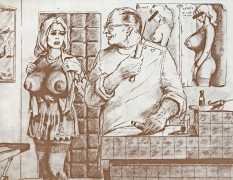

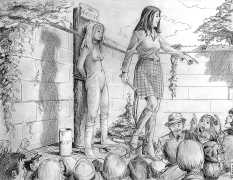

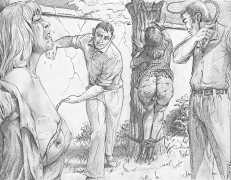

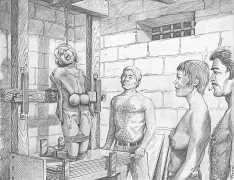

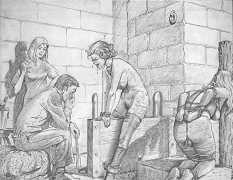

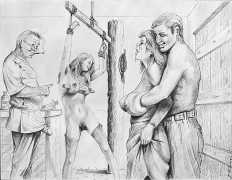

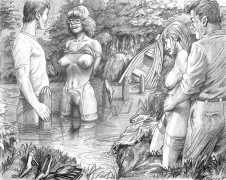

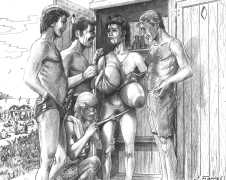

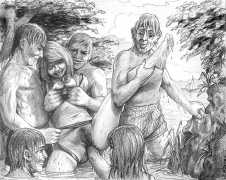

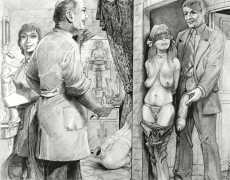

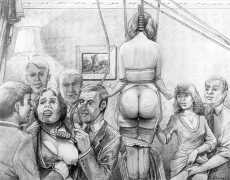

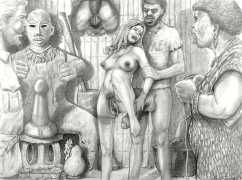

In this far-eastern-themed novel set in Saigon, the lewd cruelty of the Chinese Wang-Tchang is unleashed on a young sequestered French woman and her disobedient servants. Wooden apparatus, flagellation with nettles, a phallic Buddha statue, and the fô dog, a large block attached to a heavy platform by four powerful springs acting as tensioners, with a vertical rod ending in a screw thread – all this prefigures Farrel’s later style. The drawing is still unsure, the faces, so important in his future work, poorly worked, but these drawings already reveal Farrel’s graphic imagination.

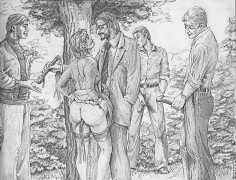

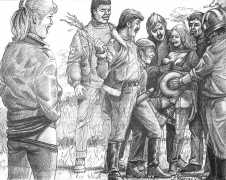

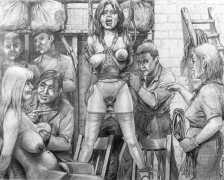

Nuits de Chine and the similarly-styled Le rendez-vous de Sodomal, which was not published until 1978, took nearly sixteen years to complete, but Farrel was not inactive on the artistic front. Frequenting Pigalle and the sex shops on Rue Saint-Denis, he met punters who commissioned drawings from him for ten or fifteen francs a throw. His clientele was pretty obsessive: ‘Jean-Pierre wanted scenes with pirates. I had a German who wanted me to ejaculate on drawings of his wife’s face. And there was Georges, a doctor involved in the Dunand affair, where a nurse had been kidnapped, raped and tortured.’

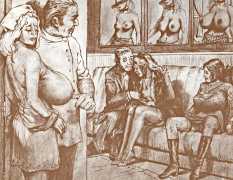

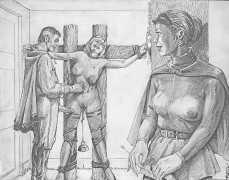

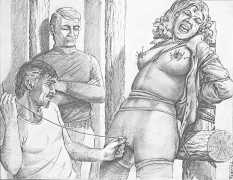

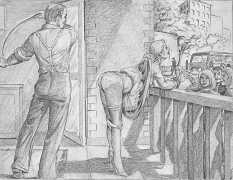

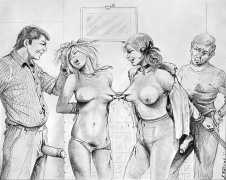

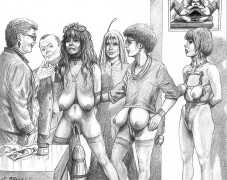

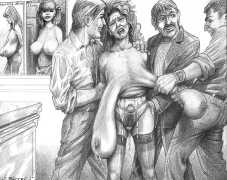

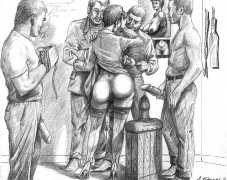

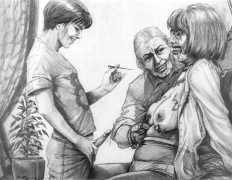

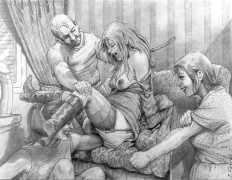

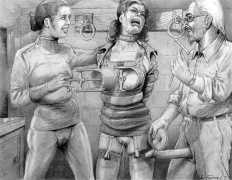

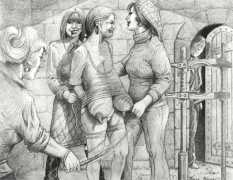

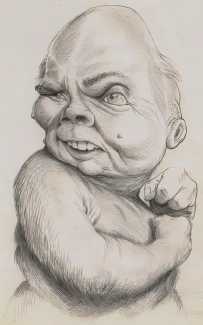

Thus illustrating the fantasies of others, Farrel continued to perfect his technique, to refine his taste for compositions with multiple characters, to familiarise himself with instruments of torture. While working in ink, however, he felt limited by the lack of subtlety; moving to his trademark pencil resulted in the style that we now think of as quintessential Farrel. The compositions in ink leave them closer to the crude SM novels of the 1930s. By adopting the pencil, Farrel finally revealed himself as the great illustrator of cruelty, of social horror without artifice.

You can read more biographical details of Joseph Farrel’s life and influences in the entry for his collection Humiliations, here.

This introduction to Farrel is paraphrased from Christophe Bier’s text, Un artiste sans limites (An Artist without Limits), in his comprehensive survey of Joseph Farrel’s work, The Farrel Artbook, published in 2017.