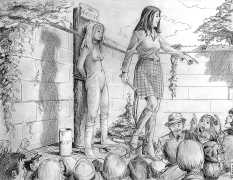

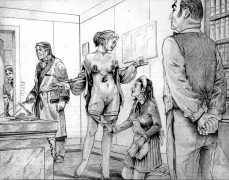

Humiliations was the first Farrel collection to be accompanied by text, like Parfums de souffrance, produced later the same year, with texts dictated by Farrel to his friend Robert Mérodack, who also assisted in translating them to English. The collection consists of 29 drawings, all depicting extreme aspects of the title.

Humiliations was the first Farrel collection to be accompanied by text, like Parfums de souffrance, produced later the same year, with texts dictated by Farrel to his friend Robert Mérodack, who also assisted in translating them to English. The collection consists of 29 drawings, all depicting extreme aspects of the title.

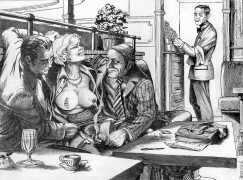

In the introduction to Humiliations, Mérodack explains why Farrel’s drawings are so relatable to contemporary French everyday life: ‘Joseph Farrel’s drawings could be nothing more than picturesque reveries. All it would take is for them to be set in an imaginary world: past, future, or mythical. But they take place in our everyday surroundings, among characters straight out of our own world. Therein lies the scandal. Joseph Farrel goes all the way. And if he shocks, it’s in the same way Sade shocked his contemporaries when they recognised themselves in his writings. Farrel excels only at the opposite end of all our reassuring clichés, in banal apartments with furniture made from the purest Formica, with seascapes painted by a weekend artist on the walls, flowery curtains, little green pot plants.’

This is possibly the most appropriate place to include what Christophe Bier much later wrote about Farrel’s early life and experiences, which helps to explain why the artist was uniquely qualified to explore the depths of sado-masochistic humiliation. Here is a paraphrased extract from The Farrel Artbook:

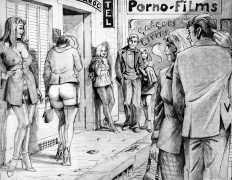

Joseph Farrel was born on February 18th 1934, on the straw mattress of a maid’s room in Thionville, without medical assistance, and the birth was only recorded on the 21st. His father left the marital home shortly afterwards. When Farrel reveals snippets of his life, it borders on torture. The cruelty of the children who bullied him, the priest of a Catholic school who whipped him bare-assed, the fifty-franc blowjobs he gave in the toilets of the Royal Colisée on the Champs-Élysées, the room of a prostitute who treated him for pneumonia after finding him collapsed on the street, the boxer Sauveur Chiocca who saved him from violent pimps, the Virgin Marys he drew in prison for other inmates, the long corridor to the morgue when he carries corpses as an orderly at Bichat Hospital, the exploiters, the class humiliation, the crooked shopkeepers on Rue Saint-Denis, the part-time jobs on minimum pay, always short of money.

Farrel’s first wife in a short-lived marriage was a whore from Algiers. He accompanied his adoptive father, an engineer, to a construction site. Some of the workers took him to the brothel, which he remembers as being rather like a slaughterhouse. He goes upstairs. The prostitute spreads her thighs, says ‘So you haven’t come to fuck?’ Lying beside him, she waits in the humid heat. We can smell the sweaty odour, see the grey sheets, the water basin, the dirty towel, the tired body, the jaded gaze, the crude makeup. Farrel the illustrator could make a sordid illustration of it, except that at seventeen he doesn’t have the sadistic confidence of his male characters. He is terrified, runs away. Farrel concludes this memory asking, ‘Is this what love is?’ Awkwardly, I ask about his relationship with women, and he replies ‘What do you want to know? For me to tell you about my hatred of my mother?’

Humiliations was published by Éditions Dominique Leroy in their Vertiges Graphiques collection. A year later it was reissued by Roger Finance for Delta Plus.