The French artist Louise Hervieu was born with congenital syphilis, which though she lived to old age severely influenced her life and her work. Her resilience and determination, however, resulted both in highly distinctive and powerful artworks, and in the French ‘carnet de santé’ (health record) system, initiated by her in 1938 and a legal requirement from 1945, whereby every French child is given a physical record of their health from the time they are born.

The French artist Louise Hervieu was born with congenital syphilis, which though she lived to old age severely influenced her life and her work. Her resilience and determination, however, resulted both in highly distinctive and powerful artworks, and in the French ‘carnet de santé’ (health record) system, initiated by her in 1938 and a legal requirement from 1945, whereby every French child is given a physical record of their health from the time they are born.

Louise Jeanne Aimée Hervieu grew up in the Normandy city of Alençon, and it was quickly apparent that art was her passion. In her early twenties she moved to Paris, and studied with Lucien Simon, René Ménard and André Dauchez. Her early canvases were filled with colourful crowd scenes, but she exhibited her paintings only once, in 1910, by which time the weakness in her muscles was making standing and painting difficult.

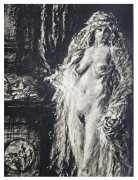

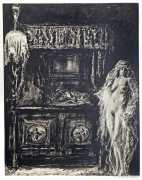

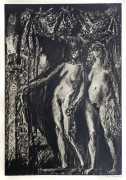

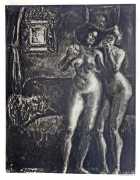

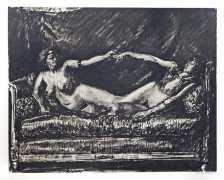

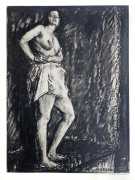

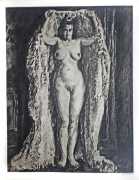

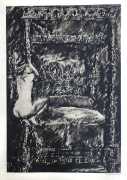

The exhibition was not a success, and that and her increasing physical disability and gradually-failing sight encouraged her to change her technique to the black and white pencil and charcoal work which was to become her unique style. During the 1910s she was close to the painter Edmond-Marie Poullain, with whom she travelled several times to Bréhal on the coast of Normandy, but several works from the 1920s suggest that she was also interested in intimate relationships between women.

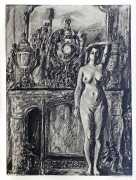

Hervieu, like many artists of the time, was very much inspired by the poems of Baudelaire and Verlaine, and she illustrated editions of Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal (1920) and Le spleen de Paris (1922), and Verlaine’s Liturgies intimes (1948).

During the late 1910s and early 20s Hervieu developed a way of working with pencil, colour wash and charcoal which was characterised by the scraping away of parts of the surface of the work to create contrast, revealing the white of the paper beneath. The art critic Claude Roger-Marx wrote of her drawings that ‘they can be compared, for their chiaroscuro, to those of Redon and Seurat; they are among the most radiant with interior life and the most obsessive that a female hand has ever traced’. The painter and writer Lucie Cousturier wrote that ‘Hervieu has much to tell us. Her charcoal lines and the scratching and biting of the paper forms complex patterns of ridges and troughs that resemble a rough sea, dappled moonlight, and the depths of her heart. She just has to sit down and say to this material, like in fairy tales, “I want flowers and fruits bursting with sap; I want lush interiors; I want flesh twisted by desire; I want playthings filled with children’s wishes.” And through her art, like a magician, she gives it to us’.

The rue Louise Hervieu, a street in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, is named after her, and there is a commemorative plaque at 55 rue du Cherche Midi in the 6th arrondissement, where she lived and worked for most of her life.

An ‘official website’ for Louise Hervieu, with more examples of her work and details about her life, can be found here (in French).