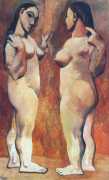

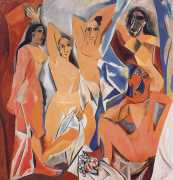

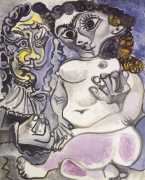

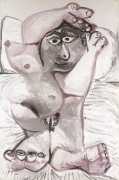

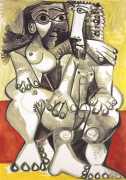

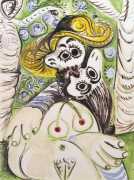

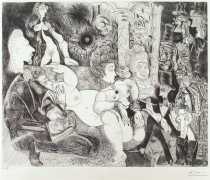

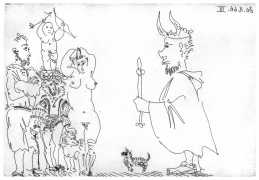

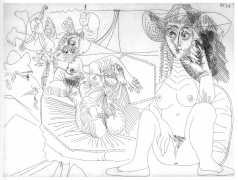

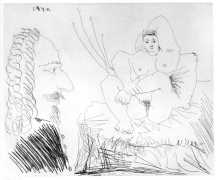

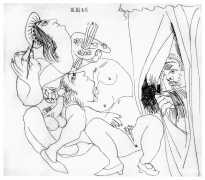

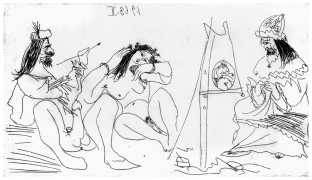

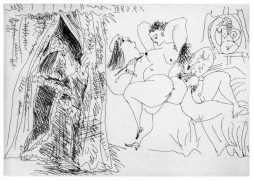

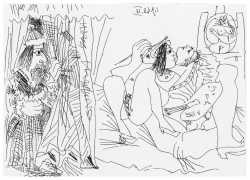

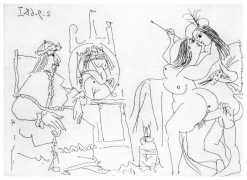

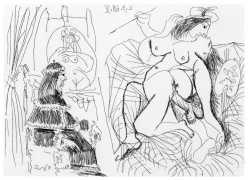

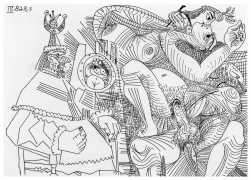

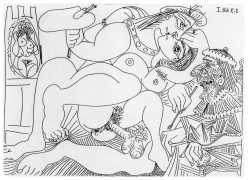

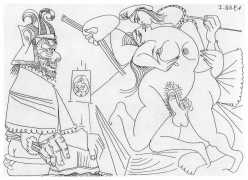

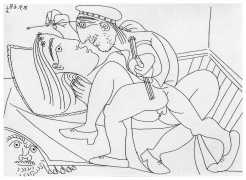

‘L’art ne peut être qu’érotique’ (Art can only be erotic), Picasso famously wrote. In 2005 Picasso’s granddaughter, Diana Widmaier-Picasso, used his assertion as the title for a book about her legendary grandfather’s mastery of the topic, explaining that Picasso himself didn’t make a distinction between art and sexuality. ‘For him it was all the same thing.’

‘L’art ne peut être qu’érotique’ (Art can only be erotic), Picasso famously wrote. In 2005 Picasso’s granddaughter, Diana Widmaier-Picasso, used his assertion as the title for a book about her legendary grandfather’s mastery of the topic, explaining that Picasso himself didn’t make a distinction between art and sexuality. ‘For him it was all the same thing.’

Up to the age of ten the Picasso family lived in Málaga in southern Spain, then in 1891 moved to A Coruña, where his father became a professor at the School of Fine Arts. Pablo showed a passion and a skill for drawing from an early age – according to his mother his first words were ‘piz, piz’, a shortening of lápiz, Spanish for pencil.

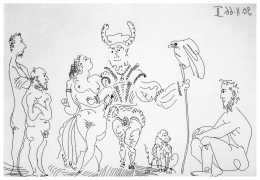

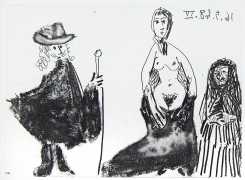

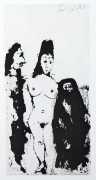

At A Coruña his father Ruiz became a professor at the School of Fine Arts. In 1895, Pablo’s beloved seven-year-old sister, Conchita, died of diphtheria, and after her death the family moved to Barcelona, where his father took a position at the School of Fine Arts. Ruiz persuaded the officials at the academy to allow his son to take an entrance exam for the advanced class, and he was admitted even though he was only thirteen. The Barcelona drawings of the 1890s — mainly brothel scenes with recognisable characters from Picasso’s circle of Bohemian friends — leave very little to the imagination. Three years later he moved to Madrid to study at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Spain’s foremost art school.

Picasso made his first trip to Paris, then the art capital of Europe, in 1900. He met the journalist and poet Max Jacob, who helped Picasso learn the language. Soon they shared an apartment, Max sleeping at night while Picasso slept during the day and worked at night. They were times of severe poverty, cold and desperation, and much of Picasso’s work was burned to keep the small room warm. Though Picasso regularly visited Spain, France was to remain his home for the rest of his life.

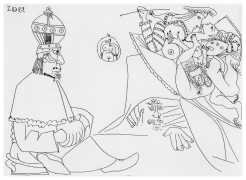

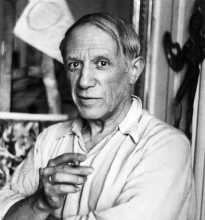

Pablo Picasso’s life has been written about in minute detail, most accessibly in Patrick O’Brian's outstanding biography Picasso: A Biography. O’Brian knew Picasso sufficiently well to have a strong sense of his personality. The man that emerges from his scholarly, passionate study is one of many contradictions: hard and tender, mean and generous, affectionate and cold, private despite the relish of his fame. Sex and money, eating and drinking, friends and quarrels, comedies and tragedies, suicides and wars tumble one another in the vast chaos of his experience. He emerges as ‘a man almost as lonely as the sun, but one who glowed with much the same fierce, burning life.’

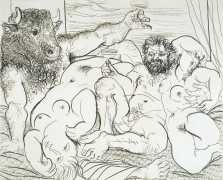

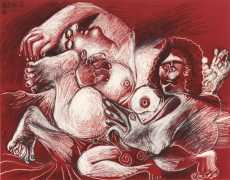

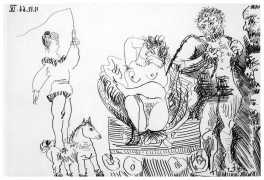

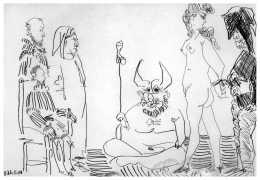

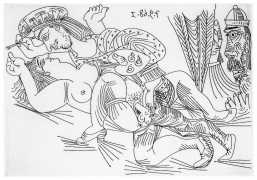

Picasso had complicated relationships with many of the women in his life – he either revered them or abused them, often both at the same time, and typically carried on romantic relationships with several women at once. He was married twice and had multiple mistresses, and it can be argued that his sexuality fuelled his art. By the time he married his first wife, the Russian ballet dancer Olga Khoklova (1891–1955), in 1918, when she was 26 years old and Picasso was 36, he had already had more or less tempestuous relationships with Laure Germaine Gargallo Pichot, Madeleine, Fernande Olivier, Eva Gouel, Gaby Depeyre Lespinasse, Emilienne Geslot and Irène Lagut. They were nearly all younger than him, and had started out as his models.

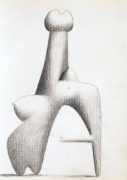

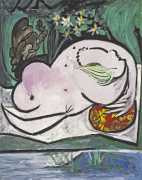

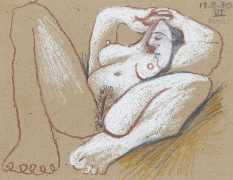

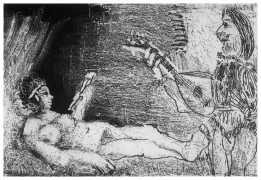

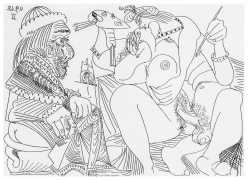

The marriage with Olga lasted ten years, but their relationship began to fall apart after the birth of their son Paulo in 1921, as Picasso resumed his affairs with other women, particularly his turbulent relationship with Marie-Thérèse Walter. By this time Picasso was already the most famous artist in the world, lived in a luxurious apartment in central Paris, owned a château in Normandy, and commuted between the two in a chauffeur-driven Hispano-Suiza. Picasso’s sexual obsession with Marie-Thérèse infused his work with new energy and changed his style. The liaison began soon after he stopped the 17-year-old girl outside the Galeries Lafayette department store, telling her ‘Mademoiselle, you have an interesting face. I would like to paint your portrait. I feel we will do great things together.’ In a 1974 interview, a year after Picasso’s death and three years before she took her own life, Marie-Thérèse told France Culture radio that Picasso possessed her – ‘That’s the way it was with him. He violates the woman first, then afterwards we work.’

The sadistic relationships didn’t stop with Marie-Thérèse. The photographer, painter and poet Dora Maar (1907–97) met Picasso in 1935 and became his muse and inspiration for about seven years. Picasso often pit her against Marie-Thérèse in a contest for his love; their affair ended in 1943 and Maar suffered a nervous breakdown, becoming a recluse in later years. Françoise Gilot was an art student when she met Picasso met in a cafe in 1943 – he was 62, she was 22. They kept their relationship a secret at first, but Gilot moved in with Picasso after a few years and they had two children, Claude and Paloma. Françoise grew tired of his abuse and affairs and left him in 1953.

Picasso met Jacqueline Roque (1927–86) in 1953 at the Madoura Pottery where he created his ceramics. Following her divorce, she became his second wife in 1961, when Picasso was 79 and she was 34. Picasso was greatly inspired by Roque, creating more works based on her than on any of the other women in his life. When Picasso died Jacqueline prevented his children, Paloma and Claude, from attending the funeral because Picasso had disinherited them after their mother had published her autobiography Life with Picasso. In 1986 Roque committed suicide by shooting herself in the castle on the French Riviera where she had lived with Picasso until his death.

In the spring of 1954 Picasso met 19-year-old Sylvette David on the Côte d’Azur. They struck up a friendship, with David posing for Picasso regularly. Picasso maded more than sixty portraits of her in a variety of media including drawing, painting, and sculpture. David never posed nude for Picasso and they never slept together – tellingly it was the first time he had worked so successfully with a model.