Yes, this is the great J.M.W. – Joseph Mallord William – who rose rapidly from humble origins to exhibit at the Royal Academy when he was just fourteen, and has subsequently earned rightful recognition as the English artist who transformed painting from stiff formalism to a freer, more imaginative and atmospheric style, often experimenting with colour and composition. During his lifetime he was known universally as William Turner; he only became widely initialised as J.M.W. as his reputation grew after his death. Altogether Turner produced more than 550 oil paintings, 2,000 watercolours, and many thousands of drawings and studies. When he died he left all his unsold works – over 37,000 of them – to the National Gallery in London, where the sheer quantity was so daunting that it took several decades to catalogue it.

Yes, this is the great J.M.W. – Joseph Mallord William – who rose rapidly from humble origins to exhibit at the Royal Academy when he was just fourteen, and has subsequently earned rightful recognition as the English artist who transformed painting from stiff formalism to a freer, more imaginative and atmospheric style, often experimenting with colour and composition. During his lifetime he was known universally as William Turner; he only became widely initialised as J.M.W. as his reputation grew after his death. Altogether Turner produced more than 550 oil paintings, 2,000 watercolours, and many thousands of drawings and studies. When he died he left all his unsold works – over 37,000 of them – to the National Gallery in London, where the sheer quantity was so daunting that it took several decades to catalogue it.

William Turner was not a gregarious person; he formed close relationships rarely and secretively. He never married, but had two close relationships with women, an older widow, Sarah Danby, by whom he is believed to have been the father of her two daughters, Evelina and Georgiana, and another widow, Sophia Booth; for eighteen years at the end of his life he lived with her as ‘Mr Booth’.

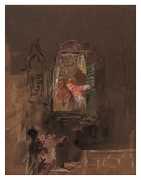

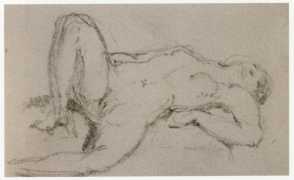

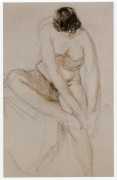

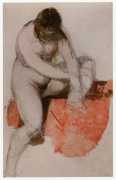

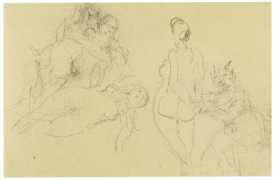

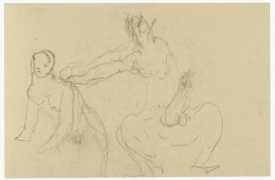

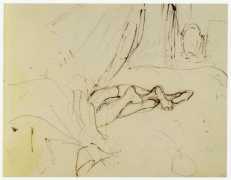

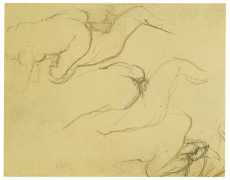

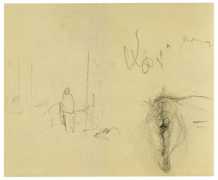

Nobody idolised Turner and his work more than John Ruskin, one of the leading intellectual, artistic, political and moral gurus of the Victorian age. Relentless critical attacks on Turner drove Ruskin to write his extraordinary defence of the artist he worshipped, the massive six-volume Modern Painters which appeared from 1843 onwards. Among other things, Turner exemplified for Ruskin his idea that great art was rooted in absolute moral integrity. A victim of the profoundly repressive sexual morality that gripped Victorian Britain, Ruskin was not merely shocked, but deeply traumatised it now seems, when after Turner’s death he discovered sketchbooks full of erotic drawings. His infamous reaction was to have them burnt. The evidence for this comes from Ruskin himself, in a letter to the man who supposedly carried out the actual destruction, Ralph Wornum, Keeper of the National Gallery, which had charge of the Turner Bequest: ‘I am satisfied that you had no other course than to burn them, for the sake of Turner’s reputation (they having been assuredly drawn under a certain condition of insanity), and I hereby declare that the parcel of them was undone by me, and all the obscene drawings it contained burnt in my presence in the month of December, 1858.’ The fact that Ruskin’s sex life left much to be desired, his marriage to Effie Gray being annulled after six years owing to non-consummation, seemed to add veracity to his motivation for the destruction of anything that might suggest that Turner had been fascinated by matters carnal.

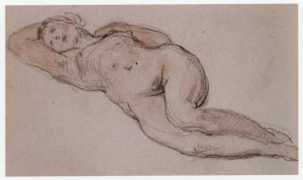

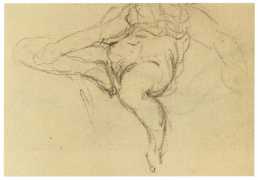

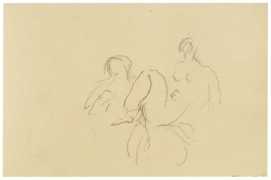

For more than a century Ruskin’s account of the burning went entirely unchallenged, but when Turner’s voluminous bequest was being recatalogued in the early 2000s it became increasingly clear that, whatever might or might not have been destroyed in 1858, a large number of studies of naked women, plus some quite explicit sex scenes, had survived.

Whatever the Victorians had tried to make – and hide – of their great painter, it is now clear that under the right circumstances William Turner was just as interested in naked bodies and their interactions as he was in stormy seas and atmospheric cloudscapes.