Ruskin’s account of the burning of Turner’s erotic drawings and paintings went unchallenged until 2012, when it was systematically and forensically disproved by the Turner scholar Ian Warrell in Turner’s Secret Sketches. Meticulously researched, he assesses the evidence, setting it in the context of the changing sexual mores of the period and of poor Ruskin’s personal agonies on this front. So scrupulous is Warrell that he can hardly bring himself to a definite verdict, leaving it to the jury of the reader. To this juror, Ruskin’s letter to the hapless Wornum seems partly wishful thinking, partly a coded instruction to him in the hope that he might carry out the deed, and partly cover for him if he did, Ruskin effectively taking ultimate responsibility. It seems fairly clear, however, that no Turners were burnt.

Ruskin’s account of the burning of Turner’s erotic drawings and paintings went unchallenged until 2012, when it was systematically and forensically disproved by the Turner scholar Ian Warrell in Turner’s Secret Sketches. Meticulously researched, he assesses the evidence, setting it in the context of the changing sexual mores of the period and of poor Ruskin’s personal agonies on this front. So scrupulous is Warrell that he can hardly bring himself to a definite verdict, leaving it to the jury of the reader. To this juror, Ruskin’s letter to the hapless Wornum seems partly wishful thinking, partly a coded instruction to him in the hope that he might carry out the deed, and partly cover for him if he did, Ruskin effectively taking ultimate responsibility. It seems fairly clear, however, that no Turners were burnt.

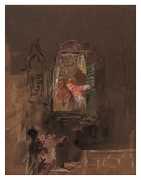

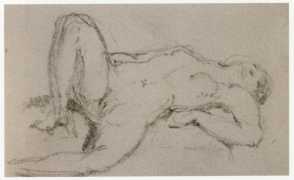

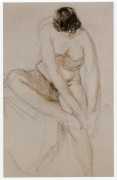

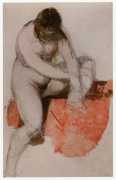

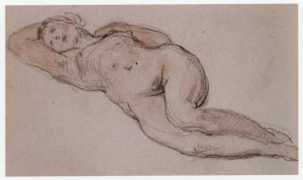

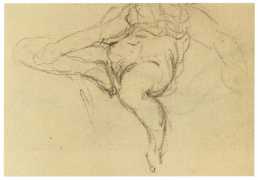

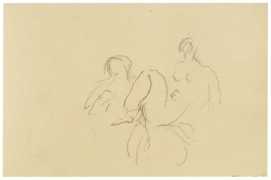

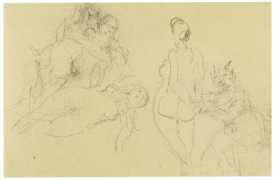

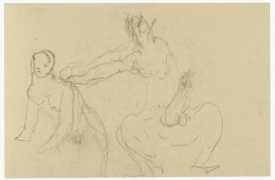

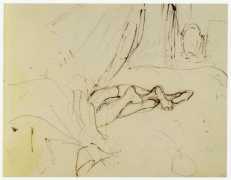

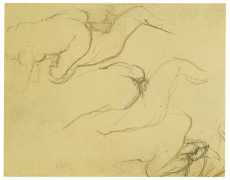

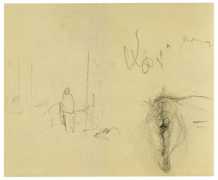

Turner’s Secret Sketches includes 65 reproductions, accompanied by commentaries. Some of the sketches, such as the two naked figures on a bed from Turner’s first European tour in 1802, are quite elaborately worked. The figures are shadowy, and Warrell dutifully reports that some commentators have seen them as male and female and some as both female. The two fashionable cartwheel hats and a pile of women’s clothes, among other details, suggest the latter, and that Turner was indulging a common male fantasy. The best of them also give the lie to the widely held notion that Turner could not draw figures. When Turner’s interest was truly engaged by the human body, he clearly could meet the challenge.

Today we value the revelation of Turner’s erotica as giving us the full picture of the man. Things were very different then, and it is ironic that Turner himself might have been delighted had Ruskin actually carried out the bonfire, the idea of which so shocks us now. This seems clear from his will, which specified only ‘finished paintings’ to be left to the National Gallery. The will, however, was legally overturned by his family, which included his two illegitimate children, to whom he had left nothing of his large fortune. In Turner’s lifetime Ruskin wilfully blinded himself to the artist’s sensuality and apparent misogyny, having fallen into the cardinal critical error of equating the man with the work. As Ian Warrell makes clear, the revelation of the erotica forced him radically to revise his view of the man, which in turn tainted his view of the work. It was a trauma that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Turner’s Secret Sketches is published by Tate Publishing; we have reproduced here just 26 of the 65 reproductions, so if you would like to see more, plus Ian Warrell’s fascinating commentary, do buy the book.