Clara Tice, who became known as ‘The Queen of Greenwich Village’ – the artistic heart of New York, especially in the early decades of the twentieth century – was an original and highly creative artist and illustrator. She always said that she had been drawing as long as she could remember, always with the encouragement of her parents. Her mother had a wry and wicked sense of humour, which she exercised more frequently upon her three children than any disciplinary tactics, so Clara encountered none of the familial obstacles usually imposed upon other young woman of that time eager to pursue an artistic career. She briefly attended Hunter College, dropping out when she caught the attention of the painter Robert Henri, who not only accepted her as a student, but in a departure from the custom of segregating classes by gender permitted her to paint alongside the men. In Henri, she found a mentor to guide the development of her unusual avante-garde graphic style.

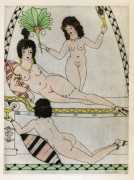

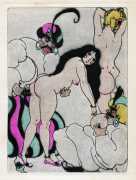

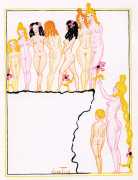

In March 1915 she found herself caught up in a sudden whirlwind of public attention. Friends had organized an impromptu exhibition of her work, pinning her sketches of athletic female nudes to the walls of Polly’s Restaurant, a popular Manhattan bohemian haunt. The drawings and their subject matter captured the attention of Anthony Comstock, the leader of the Society for the Suppression of Vice. On 13 March Comstock and his men descended upon Polly’s and attempted to confiscate Clara’s work. As the raid was in progress, patrons of the restaurant leaped to the artist’s defence. One of the outraged diners was Allen Norton, editor of Rogue magazine, who purchased the offending drawings before Comstock could remove them.

The incident at Polly’s and the publicity it spawned attracted many new admirers to Clara Tice and her art, and soon provided her with a wealth of opportunities. This was the heyday of the ‘little magazines’, low-budget publications that began to appear just prior to World War I, and her work appeared in many of them. She also came to the attention of Frank Crowninshield, who had been recently appointed editor of Vanity Fair, a magazine devoted to recording the newest events and trends in popular culture as well as more standard coverage of fashion and society. In September 1915 the magazine formally introduced the young artist to its readership – a full-figure photograph of Clara and her Irish wolfhound was published, surrounded by her trademark drawings of nude female figures.

Around this period a large number of New York’s vanguard artists were establishing themselves in Greenwich Village, where a fervour of creative camaraderie attracted many painters and poets, and Clara eagerly embraced this bohemian lifestyle. By the time her drawings first appeared in Vanity Fair she was already well-known as a Greenwich Village character. Pictures of her show a petite young woman, her fringe and short straight hair framing large intense eyes, a prominent nose, and strong chin. Frequently garbed in a costume of her own design, she proudly claimed to have been the first woman to bob her hair.

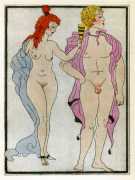

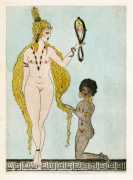

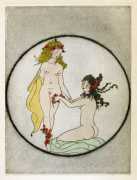

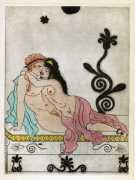

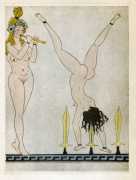

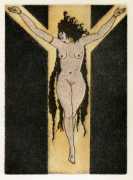

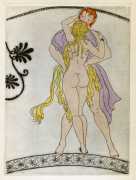

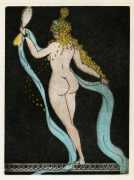

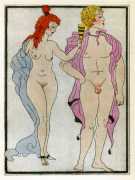

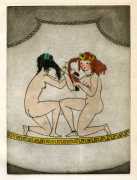

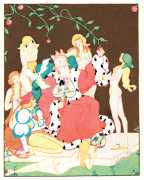

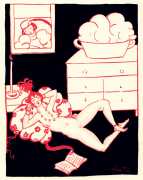

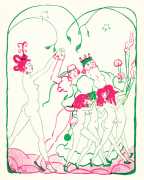

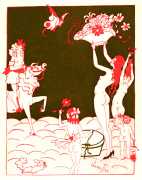

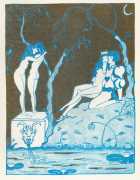

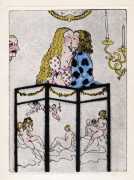

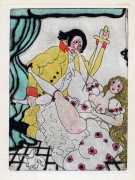

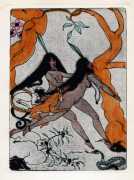

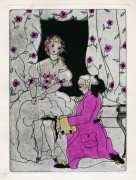

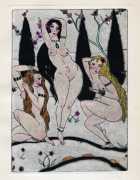

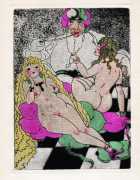

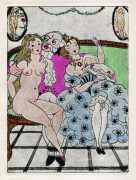

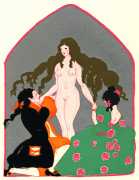

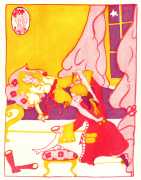

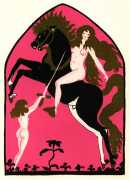

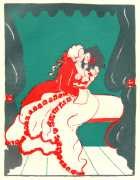

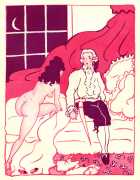

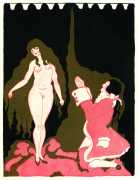

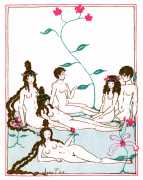

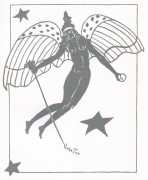

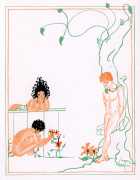

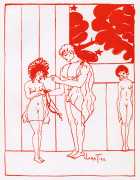

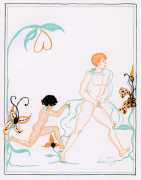

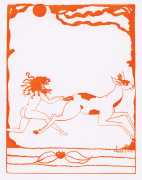

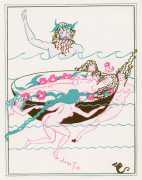

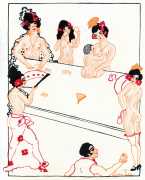

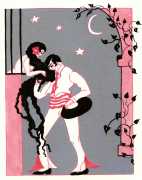

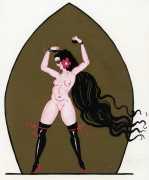

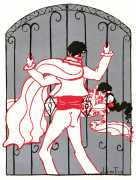

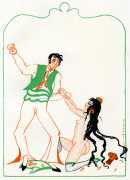

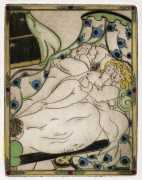

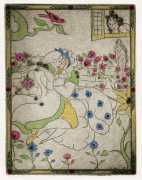

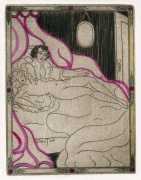

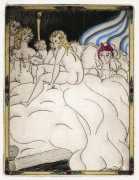

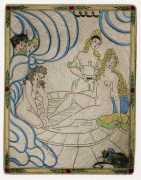

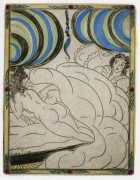

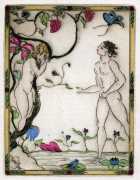

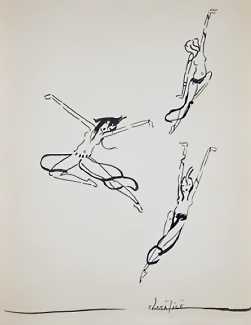

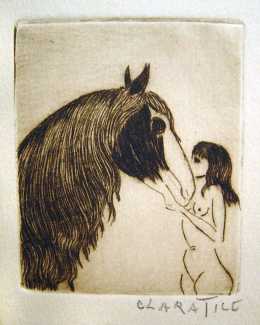

Her drawings were almost always rendered in pen and ink, with bold and confident strokes. Although her female figures were more frequently sketched as nudes or scantily clad at most, they appear today to be remarkably innocent and asexual, particularly in view of the sinister and immoral qualities heaped upon them by Anthony Comstock and the libertine aspects of sexuality accorded them by other critics.

She was an independent spirit, and though she was married briefly in 1911 (she never formally divorced), and had a male partner during the 1920s and 30s, she was as interested in animals – especially dogs and horses – as she was in close human relationships. Her illustrations clearly demonstrate her belief in strong women, and she was just as happy with women loving each other as with conventional coupledom.

During the 1920s and 30s Clara Tice was a familiar name among the art critics, publishers, painters, poets, and actors in New York City. She produced a voluminous body of work – paintings, drawings, prints and books – and her illustrations appeared in many of the avant-garde publications of the time.

Much of this information is paraphrased from Marie Keller’s excellent chapter, ‘Clara Tice, Queen of Greenwich Village’, in Women in Dada, 1998.