The French artist Philippe Cavell came, comet-like, to erotic bande desinée in the 1980s, and then seemingly disappeared again. It is when you know that ‘Philippe Cavell’ is just one side of the multi-talented architect and artist Jacques Hirou that you can understand how these flights of graphic imagination came into being.

The French artist Philippe Cavell came, comet-like, to erotic bande desinée in the 1980s, and then seemingly disappeared again. It is when you know that ‘Philippe Cavell’ is just one side of the multi-talented architect and artist Jacques Hirou that you can understand how these flights of graphic imagination came into being.

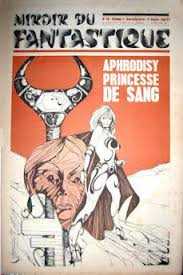

Hirou grew up in Saumur in western France, and when he left school he studied architecture in Paris from 1970 to 1978. It was during this time that his passion for comics turned from avid reader to regular contributor, and by 1971 his artwork started to appear in science fiction and fantasy publications including Miroir du Fantastique and Galaxie.

Hirou grew up in Saumur in western France, and when he left school he studied architecture in Paris from 1970 to 1978. It was during this time that his passion for comics turned from avid reader to regular contributor, and by 1971 his artwork started to appear in science fiction and fantasy publications including Miroir du Fantastique and Galaxie.

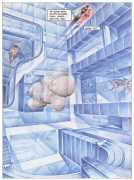

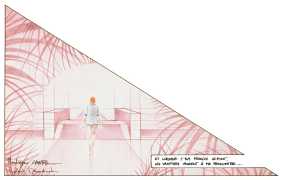

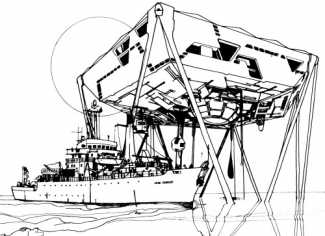

In 1974 he was part of a team of architects working on a project for a large-scale underwater community, Thalassopolis II/Université de la Mer; published in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, he worked alongside Jacques and Edith Rougerie to produce an imaginative plan for a futuristic city. Underwater art is a theme he would return to.

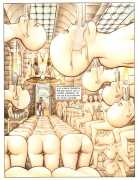

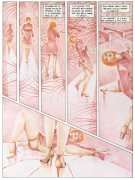

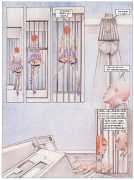

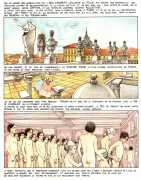

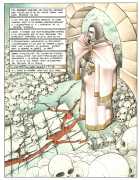

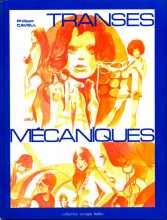

In 1979, now in his thirties, Hirou adopted the Cavell pseudonym for the first of a series of erotic comic books. Dominique Leroy published Transes Mécaniques (Mechanical Trances), a collection of short stories, which proved popular enough to follow it up with Nini Tapioca, a tale of sexual identity and a critique of a fashion industry which does its best to turn us all into identical stereotypes. Hot on the heels of Nini came his first Sade adaptation, Juliette de Sade. In 1981, working with author Robert Mérodack, he produced Jessica Ligari, and a year later returned to Sade with L’ermite de l’Apennin (Hermit of the Apennines).

In 1979, now in his thirties, Hirou adopted the Cavell pseudonym for the first of a series of erotic comic books. Dominique Leroy published Transes Mécaniques (Mechanical Trances), a collection of short stories, which proved popular enough to follow it up with Nini Tapioca, a tale of sexual identity and a critique of a fashion industry which does its best to turn us all into identical stereotypes. Hot on the heels of Nini came his first Sade adaptation, Juliette de Sade. In 1981, working with author Robert Mérodack, he produced Jessica Ligari, and a year later returned to Sade with L’ermite de l’Apennin (Hermit of the Apennines).

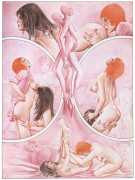

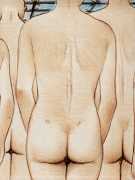

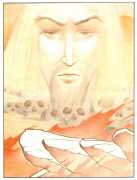

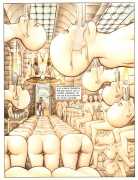

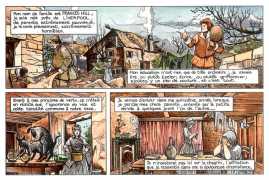

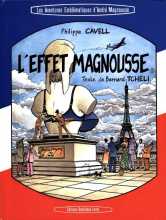

Jacques Hirou’s best-known bande desinée under the Cavell nom-de-plume is his 1984 L’effet magnousse (The Magno Effect), a science fiction story based on a screenplay by Bernard Tchéli; the ‘Cavell’ period ended with what is probably his best work, for an adaptation of the erotic classic Fanny Hill.

Jacques Hirou’s best-known bande desinée under the Cavell nom-de-plume is his 1984 L’effet magnousse (The Magno Effect), a science fiction story based on a screenplay by Bernard Tchéli; the ‘Cavell’ period ended with what is probably his best work, for an adaptation of the erotic classic Fanny Hill.

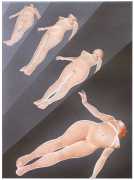

After the late 1980s Hirou settled back into the world of architecture, maintaining a busy Paris practice, but he never completely left the world of experimental art. In 2014 he worked with the Stade Nautique (Nautical Stadium) at the coastal resort of La Teste de Buch near Bordeaux to create a unique pictorial journey between water and air entitled ‘La grand bleu’ (The Big Blue), consisting of 42 paintings immersed 20 metres deep in a diving tank. The paintings depicted magical underwater scenes, but once immersed they could only be seen by those prepared to dive to find them. Hirou said of this work, which probably applies to much of his output, ‘I think of my art as a door to another reality, not just the one imposed on us. Everyone has the freedom to reach it if they make the choice.’

After the late 1980s Hirou settled back into the world of architecture, maintaining a busy Paris practice, but he never completely left the world of experimental art. In 2014 he worked with the Stade Nautique (Nautical Stadium) at the coastal resort of La Teste de Buch near Bordeaux to create a unique pictorial journey between water and air entitled ‘La grand bleu’ (The Big Blue), consisting of 42 paintings immersed 20 metres deep in a diving tank. The paintings depicted magical underwater scenes, but once immersed they could only be seen by those prepared to dive to find them. Hirou said of this work, which probably applies to much of his output, ‘I think of my art as a door to another reality, not just the one imposed on us. Everyone has the freedom to reach it if they make the choice.’