Sergei Eisenstein is probably the best known Russian film-maker of all time, his works including the silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), and the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1944).

Sergei Eisenstein is probably the best known Russian film-maker of all time, his works including the silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), and the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1944).

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein was born in Riga, now in Latvia but then part of the Russian Empire. His family moved frequently in his early years, as Eisenstein continued to do throughout his life. His father, Mikhail Osipovich Eisenstein, was an architect, and his mother, Julia Ivanovna Konetskaya, the daughter of a prosperous merchant. In 1905, following the Russian Revolution, his mother left Riga for the relative safety of St Petersburg; he only saw his father briefly afterwards, before his parents divorced and Julia moved to France.

Eisenstein studied architecture and engineering at the Petrograd Institute of Civil Engineering, and in 1918 joined the Red Army. In 1920 he moved to Moscow, and began his career in theatre working for Proletkult, an experimental Soviet organisation aspiring to modify existing artistic forms and create a revolutionary working-class aesthetic.

1925 was a turning point for Eisenstein, the year when he filmed Strike and Battleship Potemkin. Positive feedback led to him directing October: Ten Days That Shook the World as part of a grand tenth anniversary celebration of the October Revolution of 1917. While critics outside Soviet Russia praised these works, Eisenstein’s focus in the films on structural issues such as camera angles, crowd movements and montage brought him under fire from the Soviet film community. This forced him to issue public articles of self-criticism and a commitment to reform his cinematic visions to conform to the increasingly specific doctrines of socialist realism.

In the autumn of 1928 Eisenstein left the Soviet Union for a tour of Europe, accompanied by his collaborator Grigori Aleksandrov and cinematographer Eduard Tisse. For Eisenstein this was an important opportunity to experience cultures outside the Soviet Union. He spent the next two years touring and lecturing in Berlin, Zürich, London and Paris. In April 1930 the film producer Jesse Lasky, on behalf of Paramount Pictures, offered Eisenstein the opportunity to make a film in the United States. He arrived in Hollywood in May 1930, along with Aleksandrov and Tisse, to discuss possible film projects, but all his suggestions, including works by Theodore Dreiser and George Bernard Shaw, were turned down. The final straw came when Frank Pease, president of the Hollywood Technical Director’s Institute and an ardent anti-communist, mounted a public campaign against Eisenstein. Paramount declared their contract with Eisenstein void, and the Eisenstein party were treated to return tickets to Moscow at the company’s expense.

Rejected by both Hollywood and the Soviet film industry, the next important phase in Eisenstein’s career came as a result of an invitation from the prominent American socialist author Upton Sinclair. Sinclair’s works were widely read in the USSR, and were known to Eisenstein. The two admired each other, and by October 1930 Sinclair had secured permission for Eisenstein to travel to Mexico to make a film there. After much discussion the title for the project, ¡Que viva México!, was decided on. Whilst in Mexico, he mixed socially with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Eisenstein admired these artists and Mexican culture in general, and they inspired him to call his films ‘moving frescoes’. The left-wing American film community eagerly followed his progress.

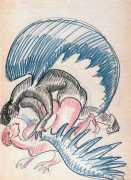

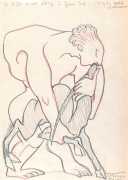

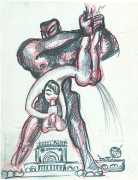

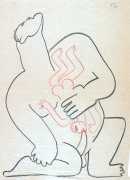

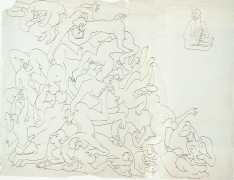

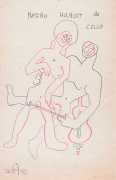

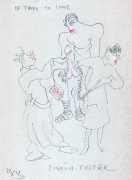

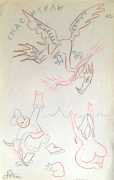

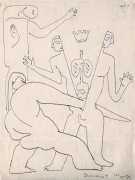

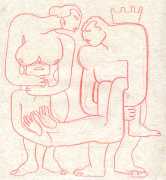

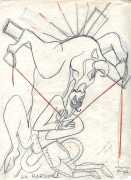

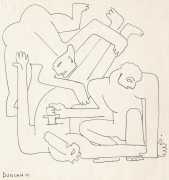

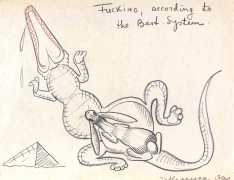

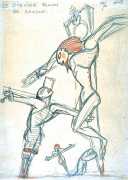

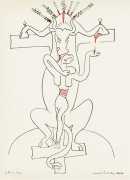

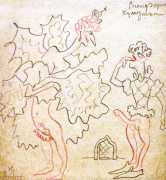

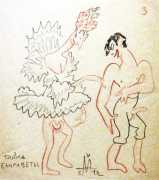

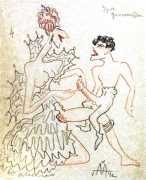

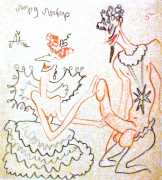

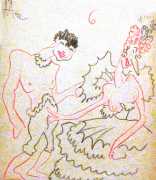

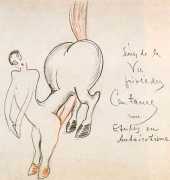

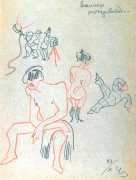

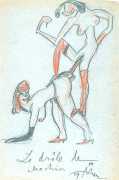

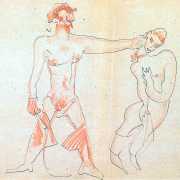

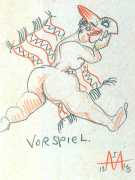

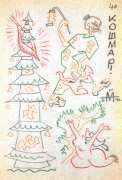

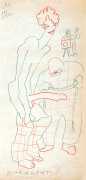

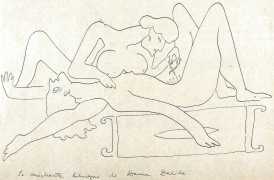

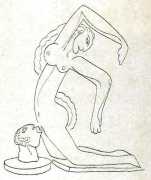

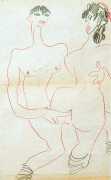

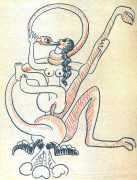

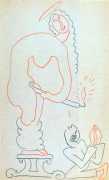

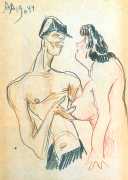

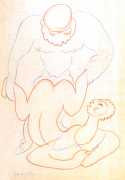

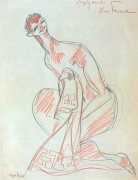

Resulting from Eisenstein’s prolonged absence, Joseph Stalin sent a telegram expressing concern that Eisenstein had become a deserter. Sergei entreated Upton Sinclair and his wife Mary to negotiate with Stalin, which led to a major row between the film-maker and his sponsors, and forced the production to close down. Eisenstein now headed for the American border, where a customs search of his trunk revealed a cache of his erotic sketches and drawings. His visa had expired, and Sinclair’s contacts in Washington were unable to secure him an additional extension, so after a month’s stay at the border outside Laredo, the group was issued with a 30-day pass to allow them to travel to New York and thence depart for Moscow.

Eisenstein’s foray to the West made the staunchly Stalinist film industry look upon him with a suspicion that would never completely disappear. He apparently spent some time in a mental hospital in Kislovodsk in July 1933, ostensibly a result of depression born of his final acceptance that he would never be allowed to edit the Mexican footage. He was subsequently assigned a teaching position at the State Institute of Cinematography where he had taught earlier, and in 1933 and 1934 was in charge of writing the curriculum.

In 1934 Eisenstein married filmmaker and screenwriter Pera Atasheva (Pearl Moiseyevna Fogelman, 1900–65). There have been debates about Eisenstein’s sexuality, though he described himself as asexual, telling his close friend Marie Seton that ‘those who say that I am homosexual are wrong. If I were homosexual I would say so, but I have never experienced a homosexual attraction, despite the fact I have some bisexual tendency in the intellectual dimension, like for example Balzac or Zola.’

Eisenstein was able to ingratiate himself with Stalin for ‘one more chance’, and he chose to film a biopic of Alexander Nevsky, with music composed by Sergei Prokofiev. The result was a film critically well-received by both the Soviets and in the West, and which won him the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize.

Eisenstein’s 1944 film Ivan the Terrible Part I, presenting Ivan IV of Russia as a national hero, won Stalin’s approval and another Stalin Prize, but the sequel, Ivan The Terrible Part II, was criticised by the Soviet authorities and went unreleased until 1958. All footage from Ivan The Terrible Part III was confiscated whilst the film was still incomplete, and most of it was destroyed, though several filmed scenes survived.

Eisenstein suffered a heart attack on 2 February 1946, and spent much of the following year recovering. He died of a second heart attack on 11 February 1948. His body lay in state in the Hall of the Cinema Workers before being cremated on 13 February, and his ashes were buried in Moscow’s Novodevichy Cemetery.