Of Thomas Rowlandson’s massive output of prints, around a hundred can be classified as erotic, or in more genteel terms ‘amorous’. Most of the best known were collected in a 1969 Cythera Press edition entitled The Amorous Illustrations of Thomas Rowlandson, accompanied by historic and general introductions by art historian and critic Gert Schiff (1926–1990). Below we reproduce his specific introduction to Rowlandson’s erotic prints.

ROWLANDSON’S EROTIC ILLUSTRATIONS

The main bulk of Rowlandson’s erotic drawings, insofar as they were done for the Prince Regent, is part of the notorious George IV collection at Windsor Castle; other specimens are in the Victoria and Albert Museum and in the British Museum, or in private hands. The material gathered in this volume presents the same stylistic and qualitative inequality and consequently the same problems of attribution and authenticity which are raised by all of Rowlandson’s work. He used to etch designs of his friends Wigstead, Woodward, Collings, Bunbury and Nixon. He left the execution of many of his finest drawings to clumsy engravers, and he even signed copies of watercolours, if these were done by pretty girls like his niece Elizabeth Howitt. To make matters more complicated: not only were those fellow draughtsmen all deeply influenced by Rowlandson’s humour, his style and his subject-matter, but he used to improve upon their inventions to such an extent that, engraved by himself, they became almost indistinguishable from his own. In our series, quite a number of plates bear, both in conception and execution, the unmistakable stamp of Rowlandson’s mastery. A few look like his inventions executed by others, and some may even have been engraved by him after the designs of friends. Without entering into the tricky questions of connoisseurship – which should be left to the art historians – I might venture the hypothesis that the whole series of small designs with explanatory verse is etched by Rowlandson – for the letters are his – after drawings by one of his abovementioned friends.

Much more important is another observation: in subject matter and mood, all of the fifty plates in this volume have countless parallels among Rowlandson’s less overtly erotic works; their spirit, if not their execution, is always unmistakably his. It can be said that these erotic designs are nothing but bolder (or cruder) versions of some of the most frequently treated subjects in his official production: untrammelled by the restrictions of decorum, the artist raises the expression of his feelings about sex, about man and woman, about the vicissitudes of old age to uncommon heights of brutal candour. He is here as bawdy and cruel as he could ever be; completely unemotional, he depicts his comedy of morals in terms of an inexorable physiological determinism.

With only one exception, none of the dated examples is earlier than 1812, and we may well assume that the majority of these designs dates from the artist’s later years: apart from stylistic considerations, they betray too much, they speak too openly of the inner state of an ageing, or prematurely aged, man whose enthusiasms may have waned even earlier than his vitality.

This is a realm of human experience which has rarely been given pictorial expression. Moving examples which, however, rank much higher both in human content and in artistic quality, are the ink drawings which Picasso executed in 1953–4 when Françoise Gilot had left him. Here the more than seventy-year-old artist endeavoured to rid himself of the oppressive consciousness of his failure in retaining the affections of his much younger companion. He did so by depicting her as a stolid, majestic beauty, and himself as a bald, dwarfish satyr. Whether he shows himself masked facetiously as a cupid or dressed up as a torero, playing games with her that are utterly inappropriate for his age, or painting her (sometimes holding his palette in his lap like a surrogate penis), or even transformed into a monkey, that age-old symbol of lust – the artist betrays in every stroke his awareness of their ultimate incompatibility. But – and here lies the difference – Picasso was still capable of loving, his vitality had not waned (after all, Françoise had born him two children), nor had he lost that generosity of the imagination which enabled him to idealise her superior grace and vigour. He knew that, however much in the eyes of the world and even (bitter thought!) in the eyes of Francoise herself, he might resemble the ludicrous, fat little satyr, in his innermost self he was still the fervent, romantic lover. Therefore he could afford to see himself as the others looked upon him and yet not adopt their view, and he was thus spared the ensuing self-hatred and its inevitable counterpart, the compulsion to denigrate his beloved.

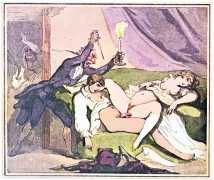

Rowlandson’s case, at least judging from the evidence of our plates, was different. His biographer, Mr. Bernard Falk, remarks shrewdly: ‘He had a fantastic craving for youth, which … expressed itself not only in a violent detestation of the physical disabilities attendant on advanced years … but of old age itself, irrespective of whether or not it was free from bodily ills. … He shrank from old age as from something unclean.’ Ribald in his youth, poor in his middle years and lonely at the end, the older Rowlandson had to endure a fair measure of precisely those disabilities – ‘failing eyesight, waning physical stamina and ominous aches and pains’ – which in his work he ridiculed. Small wonder, then, that the gouty, elephantine husband deceived by his young wife, or the impotent old lecher in helpless pursuit of lust figure so prominently both in Rowlandson’s official and his unofficial production. To a certain extent, Rowlandson draws his inspiration from literature: characters like the monk, the parson, the miser, the scholar, the Jew have been described in such unenviable roles countless times since Boccaccio and, as far as the monks are concerned, it is highly unlikely that, being an Englishman, the artist could have known any in his home country. He depicts stereotyped situations of erotic fiction, only the degree of explicitness varies. There exists, for instance, a coloured print, dated March 12, 1800 and called Hocus Pocus, or Searching the Philosopher’s Stone, which even the most meticulous keeper of a museum print room would not include among the abscondita of his collection. It shows an elderly scholar absorbed by his alchemical experiments while in the room next to his studio his young wife enjoys the embrace of an equally young gallant.

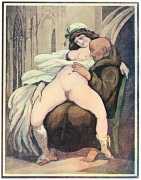

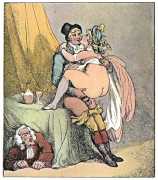

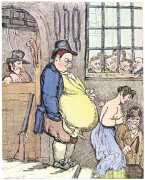

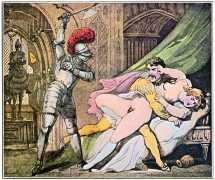

In the example reproduced in this volume, Rowlandson has turned the alchemist into an astronomer gazing through his telescope, but the arrangement of the figures with the couple seen through the open door remains the same – only that now the gallant has forced his way into the besieged fortress. Usually Rowlandson’s sympathies are, in melancholy remembrance of his roaring twenties, on the side of the young seducers; but occasionally he grants the cuckolds their revenge. Once he shows the haggard wretch ready to stab – or emasculate – the lover carelessly asleep; another time, quite in the spirit of the Gothic novels then so fashionable, he depicts the ghost of an ancestor in armour, swinging his battle-axe over the adulterous couple. Here he may have drawn upon his studies in the Armoury of the Tower, which he later used for The Microcosm of London. More poignant than these designs is a third one, The Fort. A pot-bellied jailer, attended by a grinning assistant with a cat-o’-nine-tails, leads a poor, bare-breasted victim under the gleeful leers of her male fellow-prisoners down into the dungeon. This is not a humanitarian comment upon the still barbarian penal code of the times, or the necessity of a prison reform: the stupidly avid expression on the jailer’s face and, hardly less obvious, the flap in front of his pants which describes the outlines of small and soft male organs, hint at the fact that male insufficiency quite often gives rise to sadistic aggressions against the desired female.

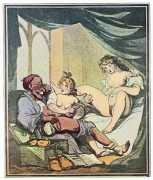

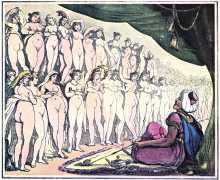

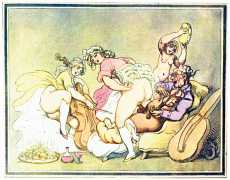

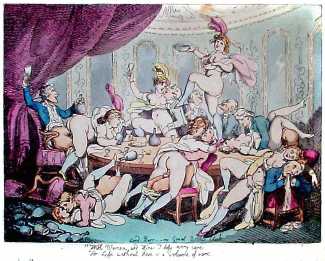

Another consequence of an aging man’s potency problems is his resorting to imaginary wish-fulfilment. Rowlandson paints the most common of such fantasies in the colors of the magical east of the Arabian Nights. This fairy-tale orient was, at least since William Beckford’s novel Vathek (1782), well established in the imagination of the English as a symbol of unfettered debauchery and carefree sensual indulgence. A touch of Beckfordian profuseness – Vathek’s worst complaint is that ‘of the three hundred dishes that were daily placed before him, he could taste of no more than thirty-two’ – can be found in Rowlandson’s Harem, where the rows of parading nude slaves seem to extend indefinitely on both sides. But, whereas Vathek constantly creates for himself new intellectual thrills and aesthetic excitements, this caliph admits little variation in the uniform display of beauty which is to goad his fatigued senses. Expressionless like dolls, lined up in almost identical attitudes, at their very best posing like such worn-out antique clichés as the Venus Callipyga or the Three Graces, these imaginary houris differ only in their perimeters: the schematism of the design as well as the pedantry with which the sexes are inscribed into their clean-shaved bellies, are all characteristic of the imaginative technique of the masturbation-fantasist. The Pasha is more cheerful: yet one could think of more ingenious acrobatics, of stronger emotional cross-currents which would unite the happy possessor and all of his six playmates in a universal give and take of lust.

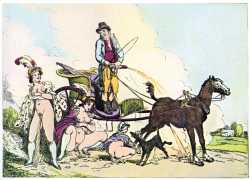

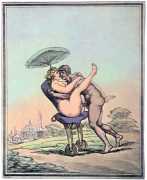

Those designs which depict couples making love in various states of locomotion also belong to the category of wish-fulfilling fantasies: not because the respective acts seem so difficult to perform, but because the underlying wish is so transparent: the galloping of the horse, the rolling of the bicycle and the jolting of the chaise are obviously intended to help the lover by infusing his amatory movements with additional verve – a fancy, not likely to be conceived by a man with a strong virile self-confidence. The scene with the naked couple, rolling all the way down toward the Fata Morgana-like, phallic city has a lyric charm of its own, faintly reminiscent of Persian miniatures. But the most extraordinary design in this group is The Swings.

High in the air above a seashore, an elderly, bespectacled man with a toad-like face, clad in the uniform of a drum-major and, as usual, with his pants removed, sits on a swing which to all appearances must be suspended in Heaven. He is swept towards a luxurious, almost naked female, equally dangling on a swing whose flight is so calculated that, at the point where their respective courses converge, his drumstick must beat, if not pierce, her drum. But alas! their mutual sway does not suffice: separated by a few inches only from their happy conjunction, they are driven apart again. The lips of the little monster shrivel up in discontent. Could there be a more telling image for an ill-mated couple’s failure?

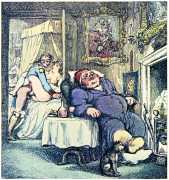

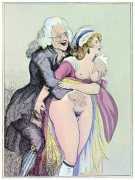

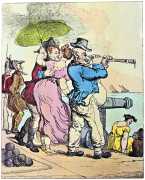

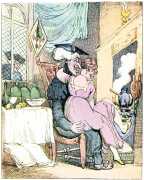

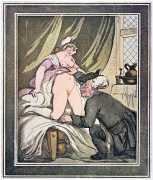

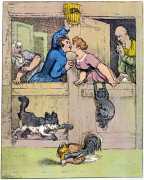

A considerable portion of the designs in this volume is devoted to another form of mental erethism: the redoubtable pleasures of voyeurism. These are curiously insistent, but also somewhat sad and embarrassing to look at: one pities the aging artist’s sexual frustration, but one resents the idea of gallant, exuberant Thomas Rowlandson turning into an obsessed Peeping Tom. However, this obsession can be traced well back into his better years and into some of his most celebrated, earlier designs. His drawings of country fairs, dance festivities or of the landing of hungry sailors at Greenwich abound with figures of ladies young and old who by some mishap have slipped and so expose, legs in the air, their most intimate attractions. Most famous of all The Exhibition Stare-Case shows an almost incredible jumble of slender and fatty females, all precipitating down the narrow, spiral approach to the Royal Academy galleries; their tight-fitting, flesh-coloured drawers make them appear naked under their fluttering Empire robes. A comparably harmless example in our series comes right out of the artist’s observations in Margate, the fashionable bathing resort of his day. Here, amidst flirting officers and sailors, an elderly provincial, beer-brewer or wine-merchant, is seen, looking through his spyglass into a distance where we may surmise some more or less naked belles swimming in the sea. He is as ugly and coarse as any of Rowlandson’s old men; not only his nose and his glass, but even the gun-barrel, which in a superb pictorial pun protrudes right in front of his belly, are phallic. On another plate, a worthy parson, apparently a close relative of Rowlandson’s immortal Dr. Syntax, is being observed by two of his brother clergymen as he warms himself at the fireplace with his handsome housekeeper on his knees; then again, we see another Reverend Sir with the face of an inquisitive bulldog kneeling in front of a pretty maid and gazing at what Fanny Hill describes as ‘the red-center’d cleft of flesh, whose lips, vermilioning inwards, exprest a small rubid line in sweet miniature, such as Guido’s touch of colouring could never attain to the life and delicacy of.’

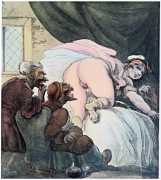

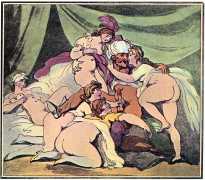

But dear Fanny’s florid style is not quite consistent with the atmosphere of these designs. There is that crude travesty of an oft-represented Biblical scene, in which a malicious Susanna willingly exposes herself to the two elders, abominable caricatures, weird productions of the artist’s cliché anti-semitism. ‘Her posteriours, plump, smooth and prominent’ do not detract their frenzied looks from the sexual centre which now, coloured with a rather un-Guido-like touch of red, looks like a wound. In the next example, the scene takes on the character of a grotesque ritual. A fatty, slovenly woman lifts her nightgown on a bed as high as a catafalque. She is surrounded by an incredible group of silly, lecherous men, this time of all ages. A stupid clerk, a short-sighted barrister with a chin like a nutcracker, an effete diplomat, wearing a monocle; a naughty nondescript, a foul-mouthed scholar, a voluminous canon with an obscene lump of a nose; a famished schoolmaster, and finally three characters whose faces do more than betray the animality of human beings: they are actually the faces of swine. All of them gaze, spellbound, at that part which to their poor little obsession is more than the whole. And the pontiff of their religion is not the generous priestess of Venus who is always ready to please, especially when it costs her so little; nay, she shows the disdain she feels for her curious congregation (behaviour which, apart from being indelicate, is also unbusinesslike).

What were they like, those wealthy amateurs for whose delectation – true delectatio morbosa – Rowlandson designed scenes like this? If they knew better pleasures, they must have been slightly appalled; if they were as poor as the cronies at the catafalque (of their dead hopes?), they cannot have enjoyed such a ruthless portrayal of their poverty. Or did they just ‘like it that way’? True, they could hardly sense, let alone understand the admixture of infantile horror in the voyeurist motive which to us, living in the age of Freud, is so evident. It is not for nothing that the formal treatment of the female organ suggested in one instance the comparison with a wound. In again another scene of exposure – with the subject reclining, putting her left leg on the shoulder of the foremost gazer – the deepest and, of course, wholly unconscious meaning of the fixation becomes evident. Note the phallic shapes in the bronze container at the right, next to the voyeurs, with their obvious hint at castration. Rowlandson could not know it, but by including them right here in his composition, he corroborated the fact that the shock which accompanied the child’s discovery that the mother lacks a penis, and the ensuing fear that she could deprive him as well of this precious ornament of his body, are still at the base of the elderly – and virtually castrated – men’s fascination with the vulva.

It have been said time and again that Rowlandson ‘had no heart to burlesque women,’ that he ‘seized avidly every opportunity to indulge in his love of the pretty’; but here at least he reveals rather ambivalent feelings about the ‘fair defect of nature’ There is an unmistakable element of sadism in the scene with the quack doctor: on the representational level, the incident is only part of the squalid routine of the brothel; but considered as a sexual fantasy, the subject comes fairly close to the games of that illiterate jailer in a Nazi concentration camp who used to don a white blouse and to play the doctor to his stripped female victims. If we add to these the subjects of female masturbation and urination, a very poor design this latter, hardly Rowlandson’s own invention), we have enumerated almost all of his morbid obsessions. Their range is rather narrow, compared, say, to the infinite variety and refinement one finds in Beardsley. They can all be reduced to an aging man’s disgust with his own barren self – it is known, incidentally, that in his later years Rowlandson even looked like his own gouty John Bull – and to the inevitably ensuing projections. The female figures in his erotic drawings have been given the following description by that great expert in all kinds of esotericism, even sexual, Joris Karl Huysmans: ‘The fat and handsome women with the rustic seductiveness of her healthy flesh, with her mien at the same time grave and sly, with her joyous skin … But it must be said that, how desirable she may ever be, the woman of Rowlandson is merely animal, without complications of the mind that interest.’ There is, of course, something about the women in these designs, those squatting hills of mellow, rosy flesh that is very pleasantly animalistic. Only, they are never persons but personages; like the inmates of the Harem, they have all the same faces which rarely reflect more than friendly interest in the acts in which they participate. More often than not, they express the boredom of the prostitute, only occasionally animated unpleasantly by a maliciousness which, psychologically speaking, is only a projection of the voyeur’s secret hatred and fear of the object of his fixation. This is the other side of the medal coined by Rowlandson’s biographers and critics, commemorating him as the unflagging panegyrist of female loveliness. We may well agree with Mr. Falk when he writes: ‘It is the very absence of emotional depth in Rowlandson’s work which constitutes his chief fascination for our troubled century ...’ But we will subscribe no more to the second main characteristic he imputes to the artist, namely his implicit acceptance of this world with its innumerable drawbacks as the best of all possible worlds.’ That hatred and that fear whose very origin we traced in the voyeurist syndrome pervade his whole work; these are the psychological conditions which enabled Rowlandson to become the merciless and often acid satirist of the society he knew. No other part of his work would have given us this key to his artistic personality; this alone justifies the publication of this volume.

We are now in a position to define Rowlandson’s place in the history of erotic art. The gods of antiquity were dead for him, too; no trace of that religious awe with which their worshippers approached the mysteries of sex can be found in his designs. Instead, he is one of the first artists who, like Sade, exposed the inevitable perversions and frustrations of the individual in whose self sex is separated from emotion. This is his specific modernity. Once more one cannot help thinking of Picasso who in his latest erotic works, the etchings done between March and October of 1968, equally dwells upon the redoubtable pleasures of voyeurism. But again, in Picasso the creative faculties of heart and brain are much greater and he spares us, even in those subjects, the sadness and embarrassment we feel when looking at the exposures of Rowlandson.

But enough of these sombre reflections. I can almost see how the countless lovers of erotic art who purchased this volume for their hearty enjoyment or, even earlier, how my gentle publishers of The Cythera Press raise their eyebrows and turn impatiently to the plates which, after all, promised more fun than that! They are right. Quite often sad people know better how to make us laugh than anybody else, and there are quite a number of plates which even the fastidious historian of culture cannot help enjoying, leaving his psychology for once at home.

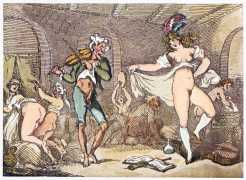

Take, for example, all the subjects connected with music and musicians. French Musicians at their Morning Rehearsal comes right out of its highly spirited and absolutely proper prototype, the watercolour A French Family of 1791, reproduced by Falk. Only the comparison reveals the comedy inherent in the transformation. For those readers who have not Mr. Falk’s volume at hand, I quote his description of the earlier design: ‘We are shown a family of professional dancers practising their steps in the privacy of their modest home. From grandfather playing the violin to granddaughter seeking with superb aplomb, despite her very tender years, to match the agility of her elders, all move in infectious rhythm with the music. Monsieur, the father, anxious not to waste any of the precious moments, has forborne to don his trousers, and the elegance of his movements and the draughty unsightliness of his undraped nether limbs form one of those ludicrous, not to say, pathetic contrasts in which Rowlandson revelled … Had she been alive, even Aunt Jane, despite her Huguenot origin, would have joined in the merriment …’ Only this last remark cannot be applied to the later design.

Or take the superb composition with the nude girl beating the tambourine in quite obviously an equally ‘infectious’ rhythm, for even the instruments of her fellow musicians are phallic, down to the last trumpet and the great horn. The plate with the girl on a swing amidst a group of clownish commedia dell’arte musicians has its prototype in a lovely, predominantly pink watercolour, owned and published by Sir Osbert Sitwell. In addition, there are The Jugglers, a fantasy based on Callot’s equally phallic etchings of the commedia dell’arte and the younger Tiepolo’s wash drawings of the Venetian carnival.

Mention should also be made of two narrative subjects. One depicts Katherine II of Russia receiving her brave Guards – without any ceremony, to be sure. It recalls inevitably a literary parallel, Joe Hynes’s malignant sneer at another female sovereign in James Joyce’s Ulysses: ‘Jesus, I had to laugh at the way he came out with that about the old one with the winkers on her blind drunk in her royal palace every night of God, old Vic, with her jorum of mountain dew and her coachman carting her up body and bones to roll into bed and she pulling him by the whiskers and singing him old bits of songs about Ehren on the Rhine, and come where the booze is cheaper.’

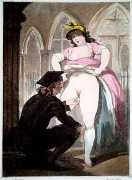

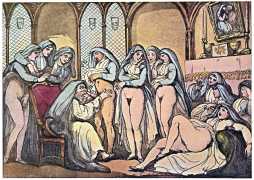

The other one illustrates a delightful piece of seventeenth century erotic fiction, Les lunettes, one of the immortal Contes of Jean de La Fontaine. An adventurous youth has found a way to enter a nunnery and, undetected under his veil, he has made a nun a mother. The abbess summons an investigation, and our hero goes to great lengths in order to hide his marks of distinction. But the mass exposure affects him so forcibly that, unfortunately just when it is his turn to be investigated, his true nature asserts itself in a movement which flips the glasses from the abbess’s nose. Every part of this scene has received the touch of a master humourist: the shock and bewilderment of the abbess, the concern of the more pious nuns who surround her, the nervous giggles of some of the others, and finally the excitement of the most emancipated one who falls back in helpless laughter.

Finally, those drawings which celebrate the joys of young and healthy people do more than balance the group with depictions of the miseries of old age. Here, one can really find, in the words of the already quoted Huysmans, ‘un humeur féroce, une gouaillerie débordante, une gaîté folle’. Rowlandson shows young men and women from all classes of society in their pursuit of pleasure. Most sophisticated, the neoclassical sculptor has created for himself an ambiance where, surrounded by Bacchic reliefs and statues of fertility goddesses, he can dream himself a Pygmalion and receive, naked, the caresses of his Galathea. It is not uninteresting to note that Rowlandson uses here observations made in the studio of one of the leading sculptors of his day, Joseph Nollekens, whom he once portrayed, modelling a group of Venus and Cupid. He depicts cosmopolitan dandies and country squires, soldiers and their gaudy superiors, all seeking, and finding, the ‘dear relief of nature.’ As always, the artist betrays here, too, that his best feelings are with the villagers on the country, where all nature is in sympathy with love, except for the old spinsters. He dwells with a bright smile upon the embarrassments of an inexperienced yokel, exposed to the tricks of London courtesans.

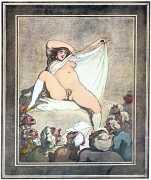

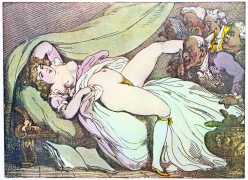

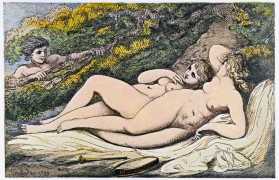

The earliest piece in the whole series, The Discovery, signed and dated 1799, is also the best. It shows two nymphs resting in a forest resort and surprised by a young shepherd. Flute and tambourine lie at their side. One is still asleep, the other is awakened and turns her head toward the impetuous youth who, in charming perplexity, suddenly lowers his eyes. The two females lie together in a tender closeness that foreshadows Courbet’s famous painting Le sommeil, or Les deux amies. Their lovely bodies have just attained their full ripeness; their outlines are composed with a rare delicacy, in complete unison. The picture breathes the spirit of eternal Arcadia. The least explicit, it is also the most erotic in this whole series. Ribald, cruel, at times prurient and obsessed, Thomas Rowlandson achieved here what only great artists can achieve: to soar high above all the lewdness of experience and to render mankind’s innate dream of innocent happiness.