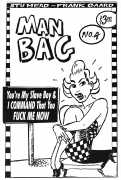

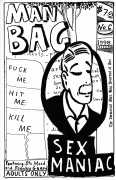

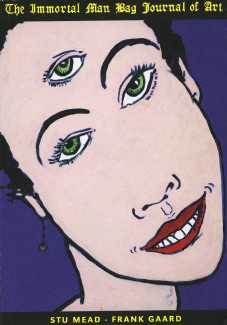

Man Bag, the xeroxed underground magazine produced by Frank Gaard and Stu Mead between 1991 and 1997, only ran to six issues, but it had an enormous influence on the zine scene in those years, liberating many artists as they explored ways of exploring transgressive sexual issues. In 1999 Pakito Bolino at Le Dernier Cri reproduced the entire contents of Man Bag as a 140-page book, and in 2017 Divus published an expanded version, adding new introductions by Frank Gaard and Stu Mead.

Man Bag, the xeroxed underground magazine produced by Frank Gaard and Stu Mead between 1991 and 1997, only ran to six issues, but it had an enormous influence on the zine scene in those years, liberating many artists as they explored ways of exploring transgressive sexual issues. In 1999 Pakito Bolino at Le Dernier Cri reproduced the entire contents of Man Bag as a 140-page book, and in 2017 Divus published an expanded version, adding new introductions by Frank Gaard and Stu Mead.

Here is the section from Mead’s introduction, ‘Elegy for Something that Won’t Die’, which provides something of the flavour of the heady period in the 1990s when Man Bag first appeared:

At the Minneapolis College of Art and Design I became a student of Frank Gaard. In the beginning I was afraid of him; I had the impression of him as the dangerous leader of a gang of punk rockers – wild, young, dressed in black. As I had put off going to art school until I was 27 I was eight or nine years older than the other students. I sat in on one or two of Frank’s lectures, and they seemed disturbingly anarchic, but I also saw him in critiques with his painting students, and was surprised at how insightful and generous he was with his students. I got to know Frank well; we lived near to each other. Sometimes I’d be anxiously hoping he’d make a comment about whatever painting I was working on. We would spend hours talking, yet he wouldn’t mention the picture which he had looked at earlier. But he always surprised me later by giving me insightful feedback and criticism. I learned a lot from him, as I continue to do.

By the late 1980s, after an especially vicious attack at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Frank was struggling to continue publishing Artpolice. At the time the US was experiencing a period of censorship based on various right-wing ideas about what kind of art should be subsidised by the government. Robert Mapplethorpe’s homoerotic photographs and Andre Serrano’s famous Piss Christ were the prime targets of zealots anxious to eliminate any government subsidies for that type of art. As part of the purge, Frank lost his job after teaching at MCAD for sixteen years.

Man Bag grew out of this period as a satirical and political example of free speech, particularly in the realm of sexual taboos. We were underground enough to pass without much notice, and we built a small network of contacts and associations on the basis of the former mailing and subscription lists of Artpolice. When I became a regular contributor to Artpolice in the late 1980s, my art pushed the project towards more extreme positions that brought other artists, gay and straight, to the project who wished to push it towards the wilder and sexier side of expression. Man Bag reintroduced an outsider viewpoint on sex and art.

We made the first issue of Man Bag in the summer of 1991. We each created around ten drawings, laid out the magazine, and went to the copy shop to make a few copies to see how it looked. Since Frank had been distributing Artpolice for years, he very quickly got Man Bag moving around the country. One of the first copies went to Factsheet Five, a magazine containing a list, along with a review, of most fanzines being produced at that time – and the early 1990s was a time of a zine boom. Factsheet Five was the pre-internet internet. From that, we got lots of orders. Even Screw magazine wrote a positive review of Man Bag, and used some of our drawings as illustrations in subsequent issues. Most people who ordered our zine were into what we were making as a kind of art object, but some ordering the book were just looking for porn, and that created tension within the project. We got some weird letters, usually pertaining to the young girls in my drawings. As a way to address this problem, Frank encouraged me to draw myself dressed like a girl – that’s how Stuartina was born. It sounds hypocritical to complain about our customers – it’s just that some of these guys obviously were looking for child porn. This was one of the factors that caused us to stop publishing Man Bag after 1997.