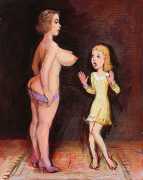

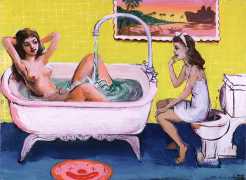

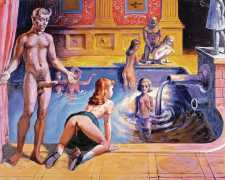

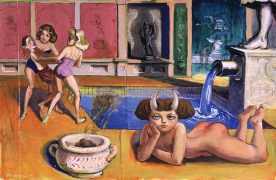

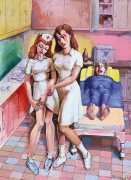

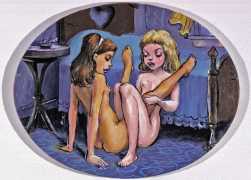

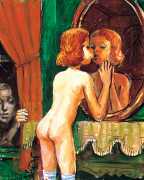

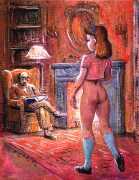

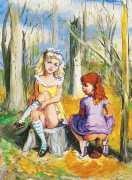

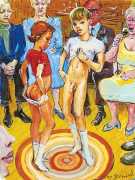

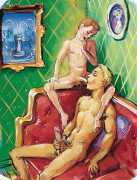

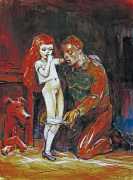

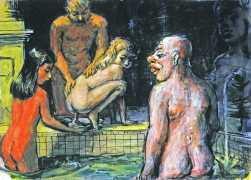

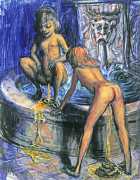

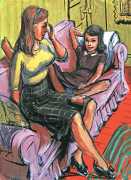

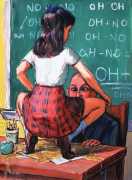

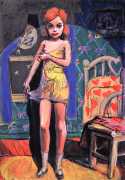

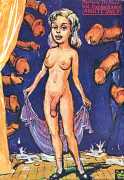

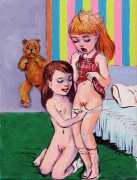

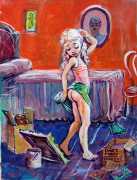

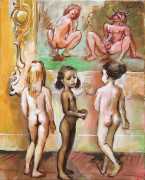

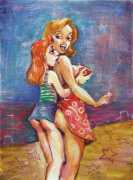

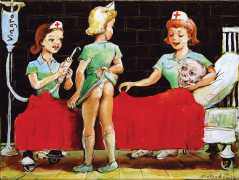

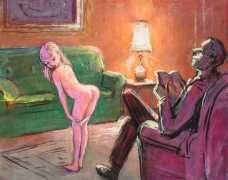

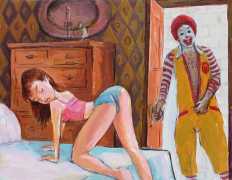

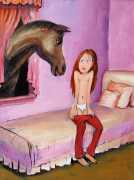

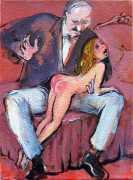

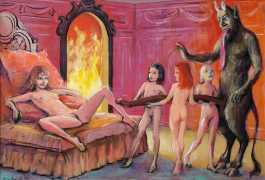

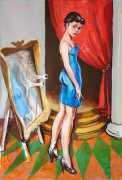

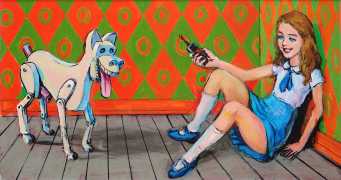

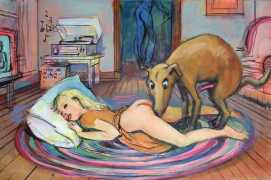

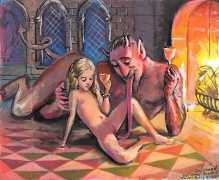

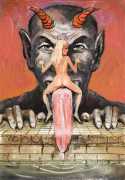

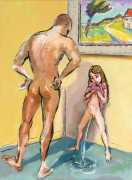

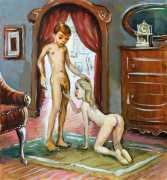

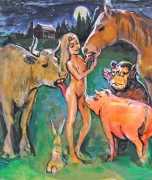

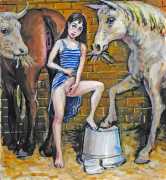

The American artist Stu (Stuart) Mead was born in Waterloo, Iowa, though for the last twenty years he has lived and worked in Berlin. Mead was born with arthrogryposis, a congenital condition affecting the joints and muscles. He is best known for his paintings of young and teenage girls exploring their sexuality. Concerning the subject matter of his work, he explains, ‘I identify with the girls in my paintings, and I identify equally with the boys and men, as well as the horses, cows and dogs. I’m just an artist with a perverted imagination trying to make good paintings.’

The American artist Stu (Stuart) Mead was born in Waterloo, Iowa, though for the last twenty years he has lived and worked in Berlin. Mead was born with arthrogryposis, a congenital condition affecting the joints and muscles. He is best known for his paintings of young and teenage girls exploring their sexuality. Concerning the subject matter of his work, he explains, ‘I identify with the girls in my paintings, and I identify equally with the boys and men, as well as the horses, cows and dogs. I’m just an artist with a perverted imagination trying to make good paintings.’

At the late age of 27, in 1979 he moved to Minneapolis to study art at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where he became acquainted with artist and future collaborator Frank Gaard, who taught at the college. Sitting in on Gaard’s lectures he found them disturbingly anarchic, but was pleasantly surprised at how insightful and generous he was with his students. In 1987 Mead began contributing to the artist zine Artpolice, which Frank Gaard edited, and participated in the publication from 1987 until its final issue in 1994. Artpolice gave Mead a forum where he could freely explore taboo themes, including adolescent sexuality, bestiality, and scatology. In 1991 Stu Mead, in collaboration with Gaard, began publishing the zine Man Bag. An offshoot of Artpolice, Man Bag focused on sexual issues.

In 1993 Stu Mead was in Vienna, where at the time the Kunsthalle Wien was staging an exhibition called Die Sprache der Kunst (The Language of Art), an examination of the use of language in art. Mead was delighted that the gallery had chosen to include Artpolice and Man Bag as an examples of current practice, even selling the magazine in its shop. Mead travelled to Paris in 1994, and sold copies of Artpolice and Manbag to Jacques Noel at Un Regard Moderne. It was here that Pakito Bolino saw copies of the zines , drawings from which he included in his magazine Le Dernier Cri. Le Dernier Cri produced the first compilation of Man Bag in 1999, and Bolino has continued to publish Mead’s artwork in several portfolios.

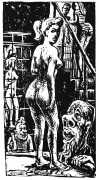

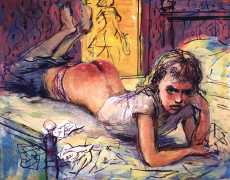

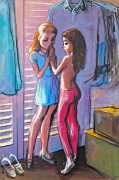

In 1994 Mead started a series of paintings based on his sexually explicit drawings, which were exhibited at Endart in Berlin in 1995. His paintings of this period were the subject of an essay titled ‘The Late Great Aesthetic Taboos’, included as part of the controversial anthology Apocalypse Culture II, edited by Adam Parfrey and published by Feral House in 2000.

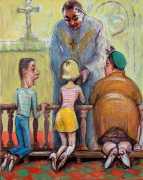

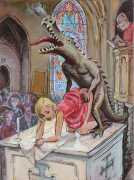

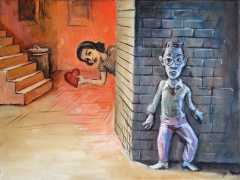

In 2000 Stu Mead moved permanently to Berlin, and in April 2004 a group exhibition, ‘When Love Turns to Poison’, was held at the Kunstraum Bethanien, showing among other Mead works the painting First Communion. During the exhibition the painting was destroyed by a religion-obsessed vandal; the exhibition became a national scandal, with conservative newspapers declaring it pornographic. Controversy also developed around an exhibition of Mead’s work at the Hyaena Gallery in Burbank, California in 2008, when four artists associated with the gallery left it in protest against Mead’s exhibition. In 2015 Mead exhibited with Reinhard Scheibner at Le Dernier Cri’s gallery in Marseilles. The right-wing French National Front protested against it for their own political purposes, which led to Pakito Bolino receiving death threats.

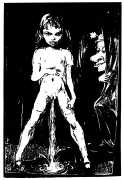

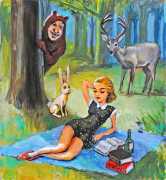

Critical response to Stu Mead’s work is not surprisingly polarised. Writing in 2006, the German art critic Hansdieter Erbsmehl suggests that ‘Pictures of little girls have so far been the highlight of Mead’s artistic production. Their age is distinguishable, but the expression of the doll-like faces almost always reflects the state of mock innocence and aggressive eroticism. In sexually charged poses, Mead lets his girls and women play out their sexual charms without delimiting them from the traditionally stereotypical understanding of roles. Mead’s girls pose more or less openly for the male voyeur, arousing erotic fantasies, sexual desires and abject obsessions. Most of the girls are small adults, for whom the elementary erotic charisma of children and innocence of childhood is denied.’

We are more inclined to side with the positive critique of radical feminist Czech sculptor and performance artist Lenka Klodová. In the introduction to the most complete collection of Mead’s work, Divus’s Stu Mead, she writes:

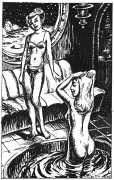

‘I bought Stu Mead’s Man Bag at Berlin’s Neurotitan book shop, and as soon as I saw it I felt as if I had drawn the pictures myself. One of the fundamental issues I was dealing with while working on my sex-positive art project for women, Ženin, was the fact that women don’t know what their genitals look like. In order to become familiar with them, they must – as with their faces – rely on touch, on other peoples’ descriptions, or on distorted reflections in the mirror. Aha, so that’s what it looks like. Something similar lay hidden inside this amazing little book full of meticulous drawings and paintings of seductive, genitalia-exploring, defecating little girls. Yes, that is how it was back then; I recognised my own prepubescent feelings and experiences, questions and misunderstandings, the first burnings of my awakening cunt, strangely friendly uncles, neighbours peeking through the curtains.’

Summing up Stu Mead’s output, the art critic Ivan Mečl writes, ‘Has anyone ever really understood Stu Mead? It isn’t at all clear from his reviews. Has Stu ever understood himself, when he often openly regrets the things he has said in media interviews? Yes, but today he chooses his words carefully. The superficial viewer might interpret his work as vulgar, and society may threaten him with punishment for crimes against the contemporary understanding of the morals of modernity. Perhaps that is one reason why he has turned his back on modern forms and methods even though he is a sensitive virtuoso who could have been a modern master capable of skilfully working with what remained of Surrealism, like Gerhard Richter in Germany and Peter Howson in England. But in the middle of his artistic career Stu ceased shaping artistic styles and, just like the disappointed Howson, who let himself be carried away by the bitterness of Christian messianism, Stu Mead has gladly succumbed to hell and to an exploration of his pleasures. There is nothing bad about it. If we cannot explore the extremes of our imagination, we cannot know where to stop in our reality.’

Stu Mead’s website, with information about his work, exhibitions and books, can be found here.