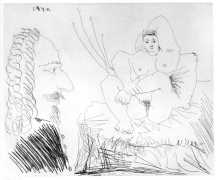

In 1965 the 84-year-old Picasso underwent major surgery, followed by a period of convalescence and slow recovery. The effect on his work was predictably traumatic – this giant of twentieth century art was forced to consider his own mortality both physically and artistically. Picasso characteristically responded with a formidable productivity, and in the final years of his life he applied himself with a single-mindedness and energy that produced an extraordinary body of work.

In 1965 the 84-year-old Picasso underwent major surgery, followed by a period of convalescence and slow recovery. The effect on his work was predictably traumatic – this giant of twentieth century art was forced to consider his own mortality both physically and artistically. Picasso characteristically responded with a formidable productivity, and in the final years of his life he applied himself with a single-mindedness and energy that produced an extraordinary body of work.

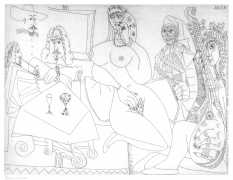

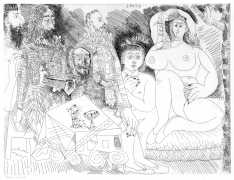

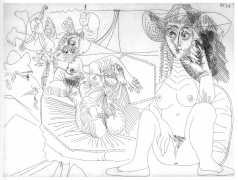

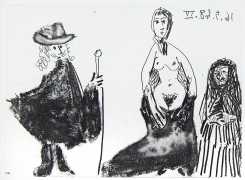

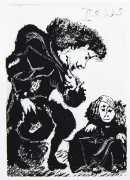

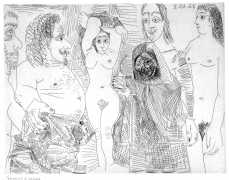

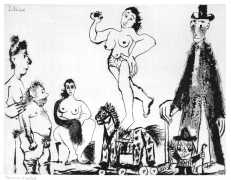

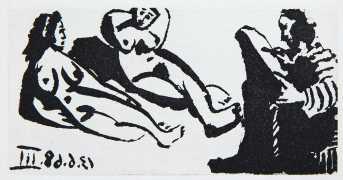

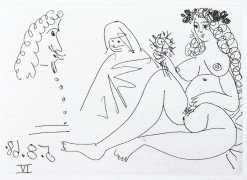

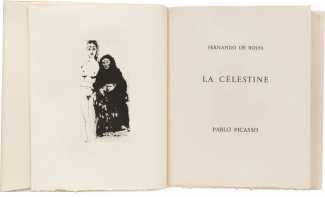

The etchings made for La Célestine are part of Picasso’s 347 Suite, a collection of 347 etchings and aquatints generated in a furious creative frenzy; Picasso turned out etchings at the rate of almost two a day between 16 March and 5 October 1968.

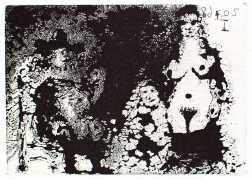

The La Célestine suite is a response to one of the most significant works in Spanish literature, properly known as La Tragicomedia de Calisto y Melibea, a dramatised novel written by Fernando de Rojas and published in Burgos in 1499. Picasso had been familiar with the work since adolescence, and in later life he collected rare editions of it. In 1903, during his ‘blue period’, he had painted the novel’s central character as a brooding, menacing older woman; what this meant to the then 22-year-old Picasso is a fascinating question.

The tale revolves around Celestina, an aged matchmaker whose corruption knows no bounds as she resorts to pulling one ruse after another in order to further her position. The old procuress and her hedonistic band of prostitutes, corrupt servants, clerics, officials, swaggering pimps and courtiers inhabit scene after scene driven by gross self-interest. The bawdy lewdness of the La Célestine plot is evident from its beginning, as is its account of selfish human indulgence, and the reader is the voyeur of all the sordid dealings of the degenerate cast of characters.

The dazzling technique displayed in La Célestine was facilitated by the celebrated printmakers the Crommelynck brothers, Aldo and Piero. They began their association with Picasso in 1961 at the rambling La Californie house and studio near Cannes, and when Picasso moved to Notre Dame de Vie in the Cannes countryside the Crommelyncks followed, opening Atelier Crommelynck in an old bakery in nearby Mougins.

The brothers came with a formidable reputation, having worked with Georges Braque, Joan Miró and Alberto Giacometti. As ever, once Picasso had got his teeth into a project his aides were sucked into the vortex. The brothers devoted their entire efforts to coping with Picasso’s graphic output until his death in 1973, producing seven hundred etchings, often working through the night and proofing successive stages so Picasso could continue working on the plate the following morning. They were staggered at Picasso’s command of the technique, commenting ‘He never ceases exploring. The astounding rapidity of his hand, combined with an equal quickness of mind, enable him to accomplish in a single operation what others would be obliged to spread over several phases.’

Most of the 347 series was produced in limited runs of 50 signed copies, and very few complete sets exist. One such set belongs to the Valencia-based Spanish bank Bancaja, and in 2009 Silvana Editoriale in Milan produced a book with illustrations of all 347 etchings, with introductions and captions in English and Italian.

Most of the 347 series was produced in limited runs of 50 signed copies, and very few complete sets exist. One such set belongs to the Valencia-based Spanish bank Bancaja, and in 2009 Silvana Editoriale in Milan produced a book with illustrations of all 347 etchings, with introductions and captions in English and Italian.