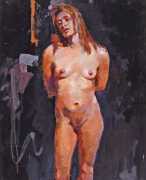

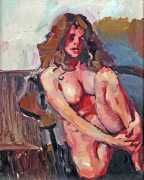

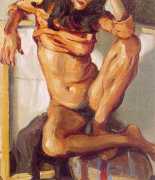

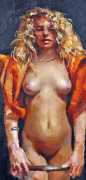

Robert Lenkiewicz sought the total fusion of life and art. His extraordinary skill in painting directly from life created a series of immense projects spanning forty years, uniquely combining visual art, philosophy and social activism.

Robert Lenkiewicz sought the total fusion of life and art. His extraordinary skill in painting directly from life created a series of immense projects spanning forty years, uniquely combining visual art, philosophy and social activism.

Lenkiewicz's life was unconventional from the start. His parents had fled to England from Germany just before the Second World War, and as with many other Jewish refugees to London few members of the extended family survived the war. They set up a small hotel in Cricklewood, and the three Lenkiewicz brothers grew up there, surrounded by elderly Jewish residents of the hotel, some of whom were refugees from the holocaust. Lenkiewicz’s early memories were of the often elderly and distressed, sometimes demented people who made their home at the hotel.

He had a difficult relationship with his mother, who doted on him but was also very controlling. He lived most of his life privately, either in his room or out in the streets. He began to paint at an early age, and when his precocity was recognised he was sent to the Christopher Wren School when he was thirteen. From there he went to St Martins, and then to The Royal Academy School. Athough he was attracted to knowledge and profoundly respected scholarship, he always said that his teachers were the paintings in The National Gallery and the books in his library. Parallel with his painting life, Lenkiewicz began to collect the books that he needed to satisfy his incessant curiosity and obsessive bibliophilia.

Robert left home after a final row with his mother when he was eighteen, and lived in a series of chaotic lodgings and studios. Life was hard but stimulating, and he was supported mostly by his girlfriends. In 1965, quite abruptly, he left London with his young wife and their baby daughter and went west, eventually settling in Plymouth. He was still intensively involved with people who the world would describe as down-and-outs, and in 1970, having no means to support himself and his growing band of dependants, decided to steal some valuable antiquarian books from the city library and sell them. He was arrested and briefly imprisoned.

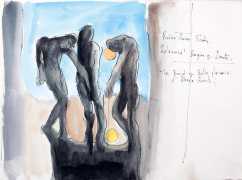

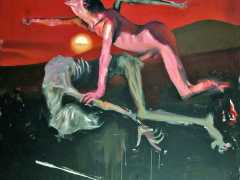

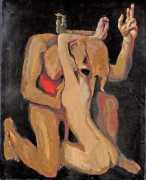

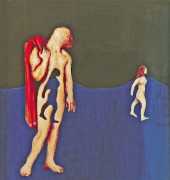

Ignoring and largely ignored by the London art establishment, Lenkiewicz created his own audience of ordinary people who would never normally set foot in an art gallery or museum. His work nevertheless confronted the most serious of themes – homelessness, mental health, old age, suicide, addiction, love, and death – often with a wry, mischievous humour. His central question – what is it that causes people to be willing to kill or die for a belief, conviction, or another person – could hardly be more relevant in today’s world.

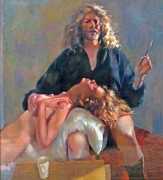

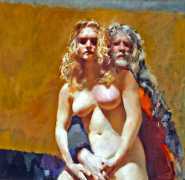

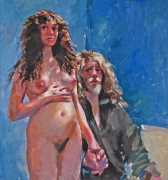

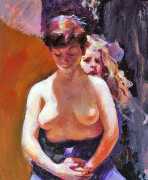

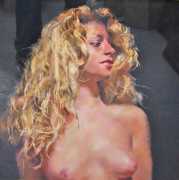

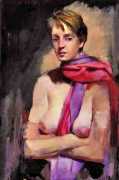

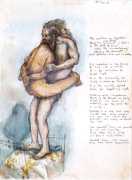

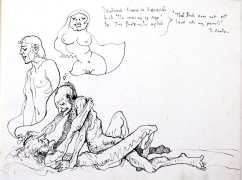

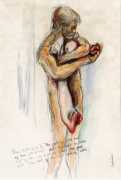

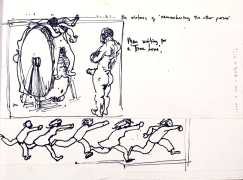

Lenkiewicz was a master draughtsman, and was profoundly involved with the people he painted. He wanted his projects to be seen in their entirety and for visitors to feel provoked by the mass of pieces that collectively created the impact he wanted. He saw himself as a presenter of information or sociological enquirer, and his main aim was to capture the transient and haunting qualities of his subject.

It is almost impossible to encapsulate briefly the life and work of such a fascinating and talented artist, but here is his friend Francis Mallett’s obituary as it was written in August 2002:

A Radical and Charismatic Painter

Rarely in recent times can the death of an artist have elicited such an emotional public response as that of Robert Oscar Lenkiewicz. The sophisticates of the London art world may well put this down as a naïve provincial phenomenon, but Lenkiewicz’s paintings communicated directly with ordinary people, who recognised that here was not only an artist of considerable talent but one who had the power to make them contemplate their own lives and the world they live in.

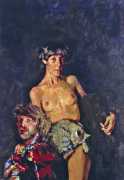

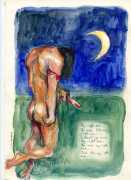

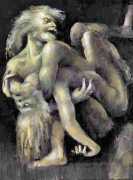

Like most things in his life, Lenkiewicz adopted a unique position towards his own paintings. At an early age he made a conscious decision to subjugate his skill to a greater service: to become a ‘presenter of information’ or a ‘sociological enquirer’ as he usually termed it. By this he meant to reveal the plain fact of a person or thing. For Lenkiewicz, the act of painting was a profoundly moving experience. ‘To paint oneself is to paint a portrait of someone who is going to die,’ Lenkiewicz would often remark when asked about his many self-portraits, ‘and the same applies if one paints anybody else.’ His main aim was to capture the transient and haunting qualities of his subject. He recognised the limitations of art, and considered it second best to the mystery of his subject’s sheer existence.

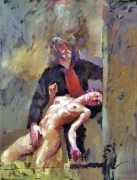

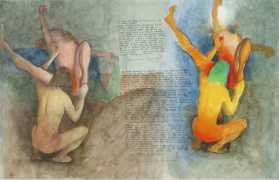

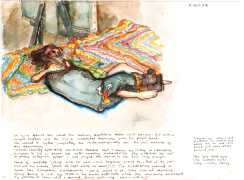

He began by recording the lives of the tramps in London and then Plymouth in his huge project on Vagrancy. In an era remembered as the fashion-conscious swinging sixties, Robert was spending most of his time painting the down-and-outs, the mentally ill and the misfits of the affluent society. Encouraged to leave London by the police for attracting too many undesirables to his Hampstead studios, Lenkiewicz soon relocated to Plymouth.

Lenkiewicz exhibited the Vagrancy Project in one of the warehouses he had commandeered throughout the city to house the down-and-outs, known as ‘Jacob’s Ladder’ (entrance was originally gained via a ladder). So ignored were the vagrants that a council official opening the exhibition remarked how fortunate Plymouth was to have very few vagrants. Lenkiewicz had shrewdly anticipated this official blindness and, on a signal from him, dozens of these ‘invisible people’ flooded into the room to make his point. Up until last year, Lenkiewicz had continued to provide a free Christmas dinner for the homeless at Plymouth’s Bretonside bus station.

This was the start of his series of ‘Projects’, in which he examined the lives of people living on the fringes of society: the mentally and physically disadvantaged, the addicts, the criminals, the sick and dying. His Projects were large in scale and ambition.

In 1971 Lenkiewicz’s taste for the grand gesture led to his creation of the famous Barbican Mural, a painting 3,000 feet square, dealing with the influence of Jewish thought on Elizabethan philosophy. Although Lenkiewicz was later rather embarrassed by it (‘fairly skilled but illustrational’), the mural became a landmark for Plymothians, as well as visitors to the city. Unforgettably on April Fool’s Day, as a result of one of his regular disputes with the local Council, the artist with typical wit whitewashed over it and replaced it with three flying ducks. In many ways, the history of Lenkiewicz is also the history of Plymouth.

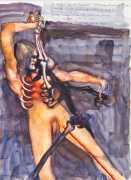

He was the most hardworking of artists, obsessive in his desire to record the event in front of him. To Lenkiewicz there was more humility involved in presenting one hundred images on a theme that didn’t worry about high art than attempting to make the perfect painting. This didn’t stop him producing some haunting early individual pieces: ‘Plymouth Mourning over its Unfortunates’; The Lynch’; ‘The Burial of John Kynance’; ‘Belle and Diogenes at Prayer’. The sombre colours – greys, greens and earthy browns – give these paintings a reflective, elegiac quality.

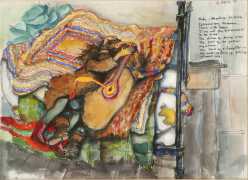

These years were a time of great poverty with a very low standard of living in various studios around the city. During the winter he would be forced to burn cardboard boxes in his studio to keep warm. The little money he earned from selling paintings was spent on paint and canvas. Often he would paint on parachute silk or sailcloth found in bins by the dossers themselves.

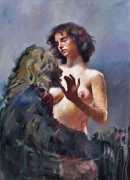

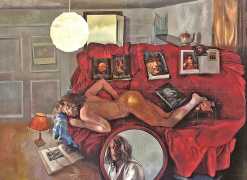

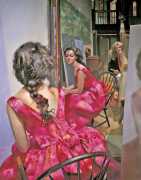

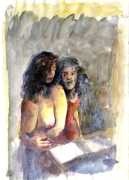

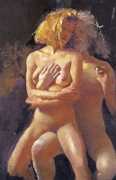

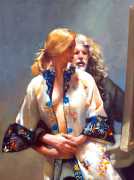

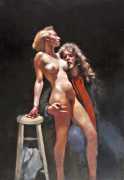

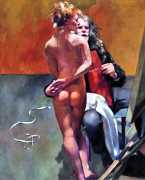

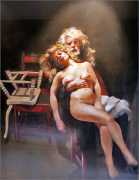

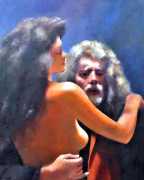

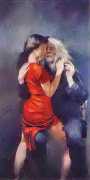

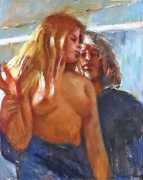

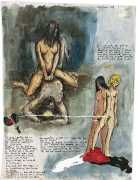

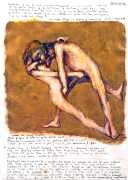

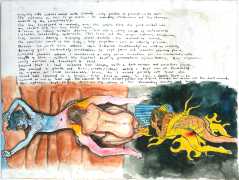

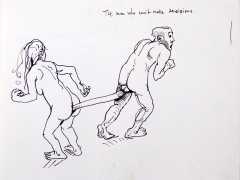

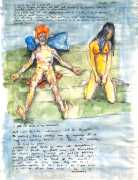

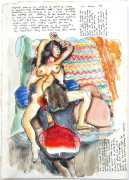

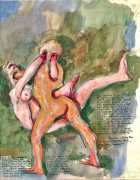

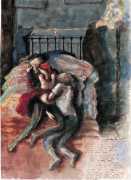

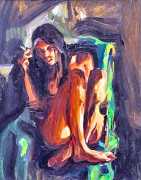

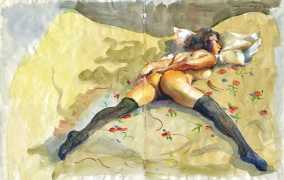

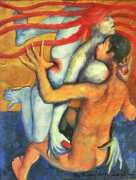

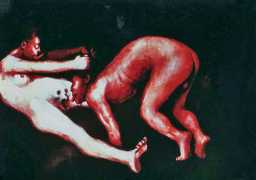

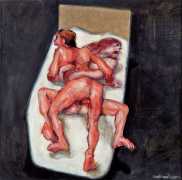

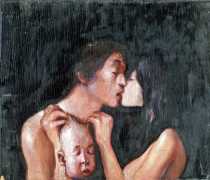

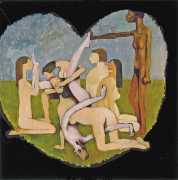

In the late seventies in a series of more private Projects, ‘Love and Romance’, ‘Jealousy’ and ‘The Painter with Mary’, Lenkiewicz was not afraid to turn his unflinching eye inwards, investigating his own personal relationships, in particular what he called the ‘falling in love experience’. These he recorded with a manic intensity in paintings and notebooks, often in a more subjective, allegorical, pictorial style. His conclusion in these investigations was that the addiction of the lover to the loved one was similar, if not identical, to the addiction of the alcoholic to drink or the fanatic to a belief. Thus was born his philosophy of ‘aesthetic fascism’, treating the other person as property. Lenkiewicz thought it was as futile to try to argue someone out of their cherished beliefs or prejudices as it was to talk them out of thinking they were in love. His point was to shock them into a new awareness, a new aesthetic understanding.

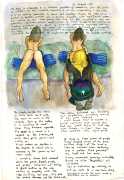

He applied this theory starkly on a sociological level in his ‘Observations on Local Education’ to society’s treatment of the young. In this project, he painted every head teacher in the city, memorably capturing the gulf between the system’s aspirations and its reality in paintings such as ‘The Blind Leading the Blind’, ‘The Burial of Education’ and ‘The Glue Sniffer’. Lenkiewicz’s hope was that people would see the exhibition and think ‘Oh my God! These are the people teaching my children!’

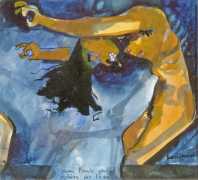

In 1994 this was followed by an ironic look at his own relationships in ‘The Painter with Women: Observations on the Theme of the Double’. For the first time Lenkiewicz chose to present the complete exhibition elsewhere than his own studios at the International Convention Centre in Birmingham in collaboration with the Halcyon Gallery. More than 35,000 people visited the show in a single week, a figure easily surpassed in 1997 by his first exhibition in a public gallery, the Robert Lenkiewicz Retrospective at Plymouth City Art Gallery.

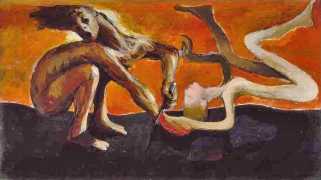

But his health was failing, the result of a serious heart condition. Undaunted, he began his largest project yet on ‘Addictive Behaviour’, with plans for over eight hundred sitters. His aim was to cover every addictive scenario, including alcoholism, theological convictions and obsessive relationships, but the project remained unfinished at the time of his death.

Lenkiewicz will be remembered as a genuine outsider and radical, consciously at odds with current thinking on ethical and artistic issues. He cared less about the opinion of the art critic than that of ordinary people. His art is generous in its ability to communicate with those who are little interested in the more esoteric world of contemporary art; it is democratic and humane but never sentimental. Above all, his paintings reveal people for what they are without moral judgement. If the task of the artist is to show what it was to be alive in a certain time and in a certain place, then the qualities of Robert Lenkiewicz’s work will increasingly become clear to future generations.

The ‘official’ Robert Lenkiewicz website, run by the Lenkiewicz Foundation, can be found here . The Lenkiewicz Foundation is a registered educational charity which was created to preserve and disseminate the artist’s library, paintings and other original works, while the family site also contains much useful and interesting information about Robert and his world.

The ‘official’ Robert Lenkiewicz website, run by the Lenkiewicz Foundation, can be found here . The Lenkiewicz Foundation is a registered educational charity which was created to preserve and disseminate the artist’s library, paintings and other original works, while the family site also contains much useful and interesting information about Robert and his world.

For anyone interested in exploring the life and work of Robert Lenkiewicz in more depth, the 2006 monograph Robert Lenkiewicz: Paintings and Projects includes contributions from many of his friends and more than eighty colour plates, while Mark Price’s two-volume in-depth biography makes fascinating and absorbing reading.

For anyone interested in exploring the life and work of Robert Lenkiewicz in more depth, the 2006 monograph Robert Lenkiewicz: Paintings and Projects includes contributions from many of his friends and more than eighty colour plates, while Mark Price’s two-volume in-depth biography makes fascinating and absorbing reading.