Félicien Joseph Victor Rops was born in Namur, Belgium, the son of a wealthy manufacturer of printed fabrics. His parents were no longer young when he was born, and his father died when he was twelve, but his early life was loving and secure. Between 1854 and 1857 he worked with Constantin Meunier and Charles de Groux, and in 1856 began to send lithographs to a student magazine, Uylenspiegel. His first experiments with etching began in 1857 and he became so absorbed with the medium that he never returned to lithography.

Félicien Joseph Victor Rops was born in Namur, Belgium, the son of a wealthy manufacturer of printed fabrics. His parents were no longer young when he was born, and his father died when he was twelve, but his early life was loving and secure. Between 1854 and 1857 he worked with Constantin Meunier and Charles de Groux, and in 1856 began to send lithographs to a student magazine, Uylenspiegel. His first experiments with etching began in 1857 and he became so absorbed with the medium that he never returned to lithography.

In 1862, Rops went to Paris to study etching with Bracquemond and Jacquemard, founders of the Société des Aquafortistes. Within six months he was elected to the committee and within a year had replaced Daubigny on its jury. It was at this stage that Rops began to etch book illustrations, and between 1864 and 1869 he produced a large number of erotic frontispieces for books published by Poulet-Malassis, Baudelaire’s publisher.

Rops married well and, though a spendthrift, never lacked for money or friends. He commuted regularly between his estate at Thozée in Belgium and Paris and Brussels, meeting novelists, collectors and artists, hunting, fishing and yachting. He travelled extensively in Scandinavia, spending much of 1874 in Copenhagen, but it was the waterfront district of Brussels that fascinated him. Absinthe drinkers, prostitutes and profligates inhabited a world which was the reverse of the comfortable, bourgeois surroundings of his youth.

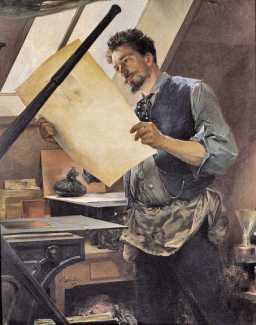

In 1875, hoping to launch a new golden age of etching, he founded the International Society of Etchers in Belgium, under the Honorary Presidency of the Countess of Flanders. He ran the Society for five years and offered a great deal of money to François Nys, who had pulled Rop’s first etchings at Delâtre’s Atelier in Paris and ran the Cadart printers as chef d’atelier, to come to work for the Society. Some Belgian etchers rallied round, but no foreign artists appeared interested. Undeterred, Rops submitted etchings under a variety of pseudonyms including ‘William Lesley’, ‘an English artist’. When doubts were raised about the existence of Lesley, Rops quickly etched a self-portrait of the mythical artist.

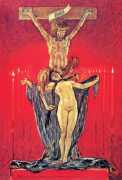

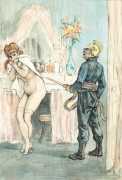

As well as Baudelaire, Rops illustrated Barbey d’Aurevilly’s Les Diaboliques, Mallarmé, Huysmans and Joséphin Péladan, who greatly influenced him through his writings. Rops was attracted by symbolism, and was encouraged by Baudelaire, the Goncourt brothers, and other friends and clients who were constantly suggesting subjects to him. Though he was born a French-speaking Walloon, he was obviously Flemish in his tastes; his tenderness and feeling for the beauty of Flemish women is clear, even when the subject is drunken, aged, a whore – or all three. Women and the craft of his art were his twin preoccupations. He would put off an important client to pursue a young model he had been told about, and would travel miles for a pretty face or body. Outside of the women of Flanders, the little Parisian nymphets excited him most: ‘One must not draw a classical nude but the nude of today,’ he wrote. ‘One must not draw the breasts of the Venus de Milo but the breasts of Tata, which are maybe less beautiful but are the breasts of today.’

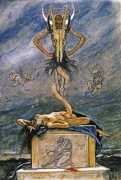

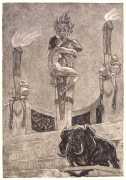

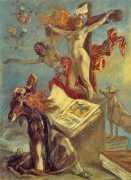

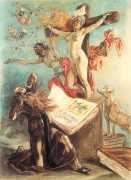

Rops’ interest in satanism was essentially literary, inextricably entwined with his eroticism and based on Christian mysticism. He was maybe overly preoccupied with sexual matters, but he excused him on the grounds that those involved were clearly atheists and positivists. In 1890, the Journal de Bruxelles wrote ‘we are not dealing here with little erotic scenes made for the delectation of old rakes. It is a profound, terrifying, entirely spiritual vision of the damnation of guilty flesh. Never has a Christian artist depicted with more vigour the ravages produced by evil; Rops is a true father of the infernal church.’ Rops did not take himself quite so seriously. Writing to his painter friend François Taelmans about his Tentation de Saint Antoine he said, ‘All this is basically only an excuse to paint from life a pretty girl who, a year ago already, cooked us some eggs and tripe à la mode de Touraine and who, for the first time, and after much persuasion, agreed to sit for her old Fély as Princess Borghese sat for Canova. I only changed the hairstyle.’

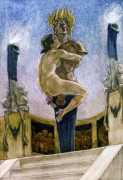

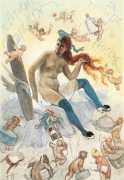

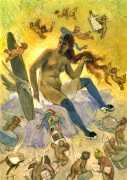

In 1897 Rops returned to Paris to meet a handsome girl ‘who wore black silk stockings with red flowers’. Having undressed her, he gave her long black gloves to wear, as well as ‘one of those enormous Gainsborough hats in black velvet with gold highlights which gives the girls of our day the insolent dignity of women of the eighteenth century.’ Thus was born his famous Pornocrates. He wrote to his friend Liesse, ‘I adore this drawing. I would show off this lovely naked girl, shod, gloved and behatted in black, silk, flesh and velvet. strolling blindfolded on a pink marble frieze, led by a pig with a golden tail, through a blue sky. I did it in four days: two in the blue satin drawing room, two in an overheated flat, filled with odours; the opopanax and cyclamen gave me a little fever which was salutory for the production.’

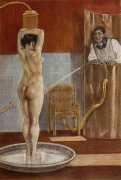

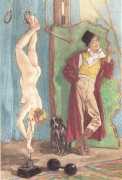

Away from his satanism, which was a reflection of his times when poets and novelists immersed themselves in black lore, and magi in their covens held sway over the famous and wealthy, Rops could be both tender and direct in his depiction of women. A sensual man, he responded to the sensuality of his models in plates like the delicious Offertoire and Nubilité, or the awkward grace of the unprofessional model in Première pose. There is a tender peasant affection in Le bout du sillon, while he sympathetically records a lesbian in Les adieux d’Auteuil.

In 1889, when Rops was ill but still overworking, the rights to reproduce all his work were sold in Brussels and bought by Gustave Pellet, who also edited Alexandre Lunois, Maximilien Luce, Toulouse-Lautrec and Louis Legrand. Pellet commissioned Albert-Bertrand to engrave a series of superb compositions in colour and black and white after Rops’ drawings and etchings.

The techniques of etching preoccupied Rops throughout his life. He was constantly experimenting, reworking his plates over a number of years; mixing soft-ground etching and aquatint; burnishing; adding drypoint, roulette and sometimes even highlighting or adding to the proof after the printing. He had no qualms about using the new technique of heliogravure for transferring a drawing to the metal plate before working on it. Many of his plates were worked in order to test and display some of these techniques.

‘I cherish my obscurity,’ he wrote towards the end of his life. ‘I don’t exhibit in order not to expose myself to receiving an honourable mention. I grant no one the right to honour me, such recognition seeming to me to be the depths of humility. I don’t know if I will produce something which pleases me; as for pleasing others, I give no more of a damn for that than for my last year’s gloves.’ He was nevertheless extremely famous in his lifetime. Octave Mirabeau, Huysmans, Péladan, Octave Uzanne, Erastène Ramiro and Emile Verhagren all wrote studies of his work, as did many lesser known writers. Several poets, including José-Maria de Hérédia and Paul Verola, wrote poems inspired by his work. He influenced James Ensor, Rodin (whom he considered the greatest sculptor of his age), and Munch, and his early work prefigured Toulouse-Lautrec. His dark mysterious plates greatly influenced the early German film directors, and in both content and style he was the precursor of art nouveau.

This text is largely an abridged version of Victor Arwas’s excellent introduction to his 1972 collection of Rops illustrations, published to accompany an exhibition in his London gallery.