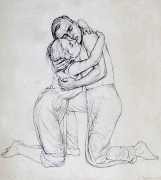

We shall probably never know the reasons for Ida Teichmann’s apparent preoccupation with naked prepubescent girls, mothers and daughters, but in many ways they were very much of their period, both culturally and artistically.

Culturally, the Germanic concept of Nacktkultur was widespread in the 1920s and 30s, promoting nakedness as a way of connecting the individual with nature, health and social reform. The German naturism movement was careful to de-eroticise the naked body, which was not particularly regarded as sexually provocative in itself, believing rather that civilisation had taught us to look upon nudity as sexual. Nakedness was portrayed as health-giving, and became politicised by radical socialists who believed it would lead to a breaking down of society and classlessness. It also became associated with pacifism. In 1926 Adolf Koch established a school of nudism, encouraging a mixing of the sexes, as part of a programme of sexual hygiene.

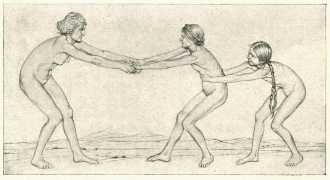

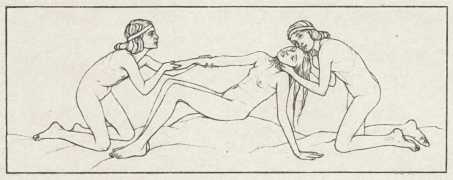

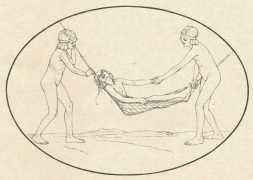

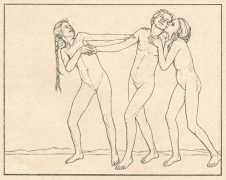

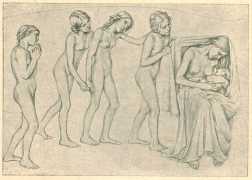

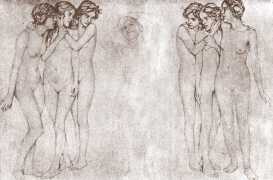

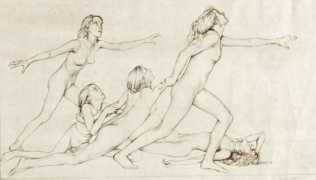

Thus Ida Teichmann’s naked teenagers were associated with a progressive world-view, and she gave them titles like ‘Die Hingerissenen’, ‘ Die Erlösten’, ‘ Die Verlassenen’, ‘ Die Entzückten’, and ‘Die Andächtigen’ (‘The Enraptured’, ‘The Redeemed’, ‘The Abandoned’, ‘The Delighted’, and ‘The Devout’).

Artistically too, the style of her drawing shares much in common with some of the Jugendstil school in Germany and Austria, and with the English Pre-Raphaelites.

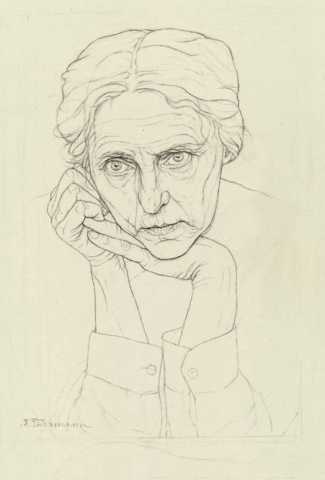

We are left to wonder how Teichmann’s art reflected her personal life. Given her change of name she clearly married, and Alfred Teichmann (1903–90) was probably her husband. Is the 1914 painting above of a mother and child a family self-portrait? Certainly by the time she made this characteristically detailed lithographic self-portrait in 1935 she knew she had accomplished the artistry she had worked for so hard.