The Borgia family dominated Renaissance Italy, and has sometimes been described as Italy’s original crime syndicate. Much maligned for their misuse of power, the Borgias are now being reassessed in our age of more secular power politics. Were Alfons (Pope Callixtus III), Rodrigo (Pope Alexander VI), Cesare and Lucrezia dastardly characters, or stereotyped as Machiavellian? Were the Borgia popes abjectly sinful, or merely worldlier than was good for their reputations? Was Lucrezia Borgia one of history’s great vixens or her powerful family’s pawn? Were the Borgias simply victims of early biographers intent on character assassination due to gender politics, or a poor understanding of how political power must always be used? What are the parallels between the abuse of power in state and religion then and now?

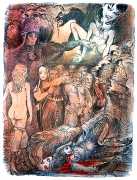

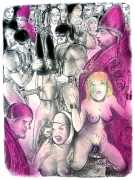

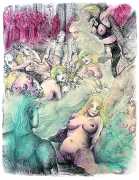

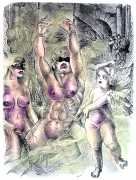

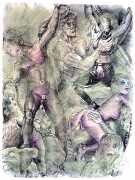

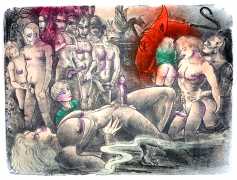

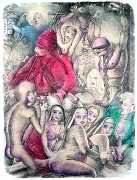

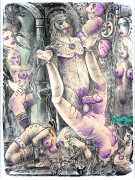

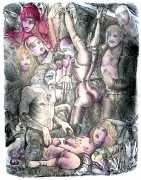

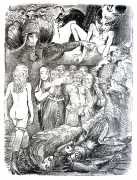

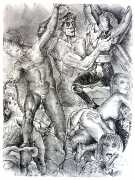

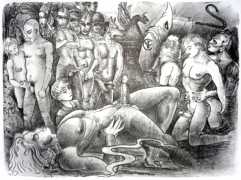

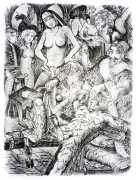

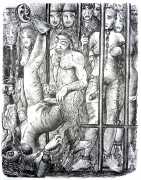

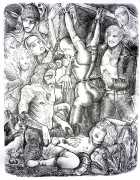

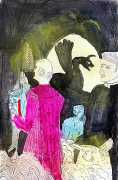

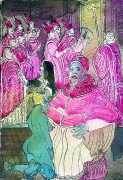

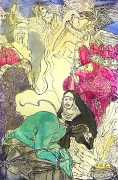

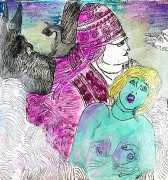

Whatever the historical truths, Katharina Kranichfeld sees many parallels between the experience of Lucrezia Borgia, her own experiences of sexual abuse, and the way that facts and rumours around the misuse of power are still rife today. This powerful series of etchings and paintings, made in 2010–11, is one of her most striking works. We show here the coloured versions, where the pale turquoise of a naked Lucrezia is contrasted with the purples and reds of church and court, the uncoloured etchings, and the paintings from the same series.

Lucrezia Borgia, the daughter of Pope Alexander VI, is given particular attention. Lucrezia is accused of is committing incest with her brother Cesare, and with her father, but it is commonly believed that that was a slander by her first husband, Giovanni Sforza, whom she married in 1493. The marriage was a political one, helping Alexander forge powerful ties with his uncle, the Duke of Milan, and she was just thirteen while Giovanni was twenty-six. Enemies of the influential family lapped up the incest stories, and rumours about Lucrezia’s general sexual behaviour were rife.

Her reputation as a poisoner arose from several mysterious deaths that occurred around the Borgia family, including her own brother, Juan. It was rumoured she wore a hollow ring, containing poison, which she would deploy at parties.

Sexual misconduct continued to follow Lucrezia, even after the death of her second husband, Alfonso of Aragon, who was attacked and strangled in his bed by an agent of her brother Cesare in 1500. The following year an illegitimate Borgia baby appeared, whose parents were never officially disclosed. Was he Lucrezia’s, with her rumoured lover Perotto? Was the boy the son of Alexander and Lucrezia? Was he the son of Cesare and Lucrezia? Two Papal Bulls were issued, one saying that Alexander was the father, the other that it was Cesare. Lucrezia acknowledged him as her half-brother.

Then the famous ‘Banquet of Chestnuts’ spread more rumours of sexual debauchery, as Johann Burchard describes: ‘On the evening of the last day of October, 1501, Cesare Borgia arranged a banquet in his chambers in the Vatican with fifty honest prostitutes or courtesans, who danced after dinner with the attendants and others who were present, at first in their garments, then naked. After dinner the candelabra with the burning candles were taken from the tables and placed on the floor, and chestnuts were strewn around, which the naked courtesans picked up, creeping on hands and knees between the chandeliers, while the Pope, Cesare, and his sister Lucretia looked on. Prizes were announced for those who could perform the act most often with the courtesans.’

Lucrezia’s reputation was not helped by the fact that she allegedly had affairs with poet Pietro Bembo, her and with brother-in-law, Francesco Gonzago. Her reputation persisted. Alexandre Dumas wrote that Lucrezia ‘had a wild imagination, was an unfaithful woman by nature, and was the daughter and mistress of her father while also engaging in intimate relations with her brother’. In 1816 the poet Byron wrote that her love letters were the ‘prettiest in the world,’ and claimed that he stole a lock of Lucrezia’s hair which was on display in the Ambrosian Library of Milan, calling it the ‘prettiest and fairest imaginable.’