Katharina Kranichfeld is not her real name, ‘Kranichfeld’ (‘field of cranes’) being the Weimar town where she grew up. She chooses to work under a pseudonym largely because her lithographs, etchings and drawings nearly all depict some aspect of sexual violence, making it difficult to find acceptable ways of presenting her work.

Katharina Kranichfeld is not her real name, ‘Kranichfeld’ (‘field of cranes’) being the Weimar town where she grew up. She chooses to work under a pseudonym largely because her lithographs, etchings and drawings nearly all depict some aspect of sexual violence, making it difficult to find acceptable ways of presenting her work.

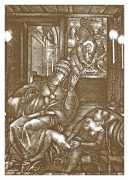

Kranichfeld studied at the Universität der Künste in Berlin, where she started to create a massive sexually-graphic work, part of which was first shown at the Kunstfest Weimar, organised by Nike Wagner. Her work later appeared in the Graz State Museum and in the gallery in Hof. During the 1990s she illustrated several poetry books for the Mariannen Press, the Corvinius Press, and Edition AHA Vienna.

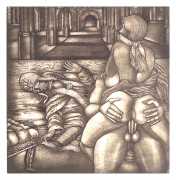

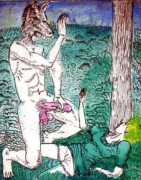

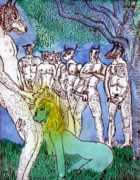

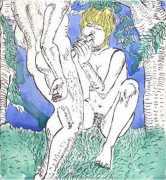

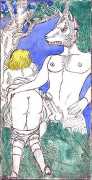

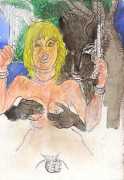

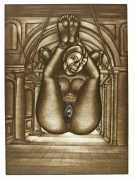

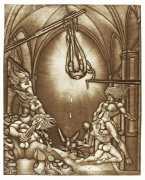

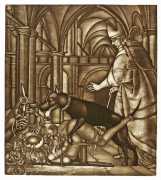

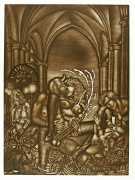

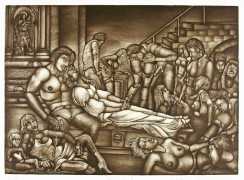

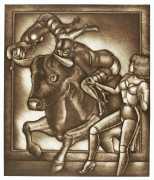

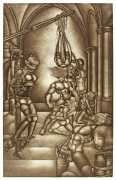

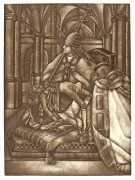

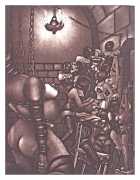

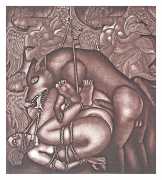

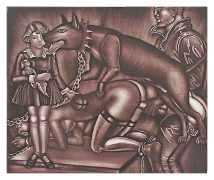

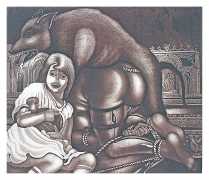

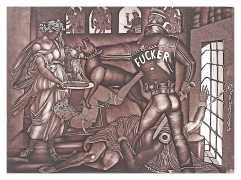

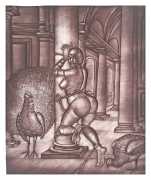

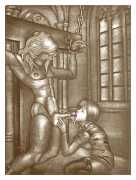

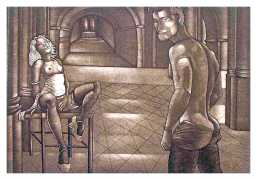

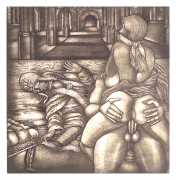

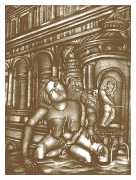

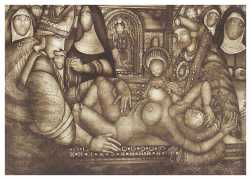

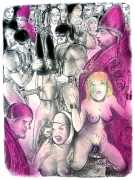

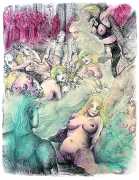

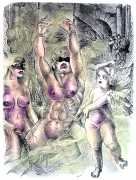

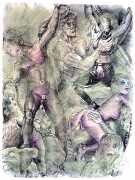

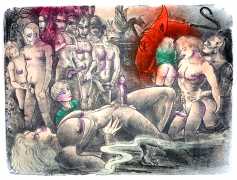

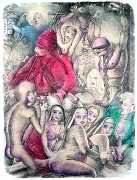

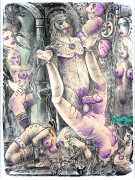

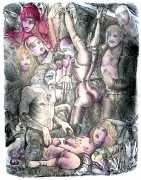

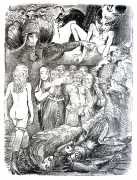

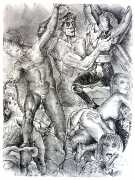

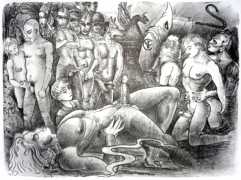

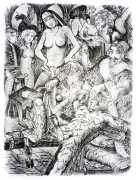

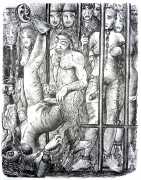

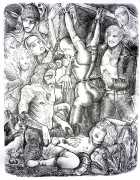

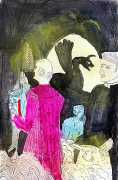

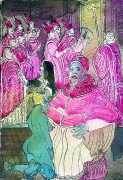

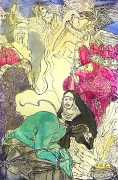

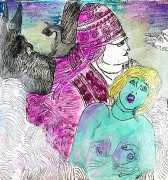

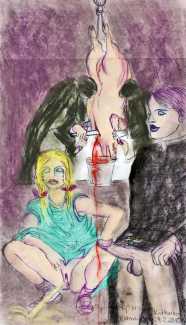

Katharina Kranichfeld works in two types of graphic media – dark and brooding etchings, and drawings in brightly-coloured crayon. The drawings are much freer than the etchings, created quickly and often quite crudely. The imagery is often quite shocking, involving sex, blood and body parts. Some of her etchings are hand-coloured, including prints from the ‘Borgia’ and ‘Zyklus’ portfolios.

In 2015 Kranichfeld produced several surrealist performance pieces which can be found on YouTube, including Hänsel und Gretel, Marmor, Stein und Eisen bricht (Marble, Stone and Iron Break), Chucky und die Prinzessin mit der Schweinemaske (Chucky and the Princess with the Pig Mask), and Knollenblätterpilze (Death Cap Mushrooms).

Much more of her work can be found on the Frankfurt Graphic Brief website, here.

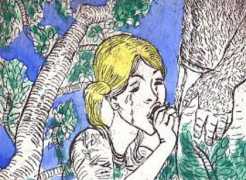

Hans-Jürgen Döpp has written about Kranichfeld’s work in a piece entitled Alice in a Wonderland of Horror, from which the following extracts are taken:

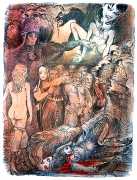

Kranichfeld’s images lead us back into a childlike fairytale world, but with the crucial difference that there is no hope, no salvation. They deliver us entirely to horror.

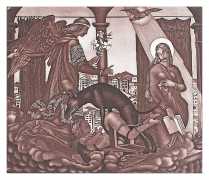

Fairy tales tell of encounters with evil, but as a rule evil is overcome with cunning – in the face of evil there is always a hope of salvation. Kranichfeld’s gloomy childhood fairy tales, however, lead only to hopeless horror.

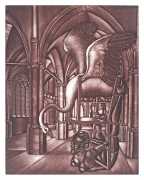

Katharina Kranichfeld has been drawing since childhood; dreams and daydreams are her artistic source. She often does this through daily trance states, often lasting several hours – ‘I have visually travelled into the past to bring out scraps of memory that are hidden deep in my memory,’ she writes. While drawing, she abandons herself entirely to intuition, reminding us of the image-finding strategies of the Surrealists, who at the beginning of the 1920s attempted to eliminate the control of reason by inducing trance states and automatic writing.

The scenarios that Kranichfeld brings out of her trances are often disturbing. The images irritate and shock us. Here are princesses with pigtails on scooters, little boys with toy trains. But look again – a wolf leaps out of the bloody mouth of the princess; the little boy dangles from a rope. Everything that a child loves, everything that is beautiful, all leads to ruin. Childlike innocence results in annihilation.

Kranichfeld’s childhood was traumatic, involving extreme sexual violence, and she is clear that the powerful impulse to create art is her attempt to free herself from this trauma. For the duration of the drawing, the past loosens its stranglehold, yet the obsessive production of new material is an indication that the satisfaction and reassurance it produces can only be short-lived.

Later in life she found understanding in the in the works of Georges Bataille and the Comte de Lautréamont. Their works, she writes, ‘led me deep into the realm of evil, into the supposedly inaccessible. They showed me another side of sexuality – the world of debauchery and horror. In particular Bataille’s Histoire de l’Oeil helped me understand that I was not alone in my trauma and horror.’

Modern art history is characterised by a de-aestheticisation of the aesthetic. A common cultural undercurrent unites such divergent art styles as Expressionism, Surrealism, Fantastic Realism and Art Brut, an undercurrent that allows for the expression of the fear, brutality and violence that underlie our history. It is this undercurrent that makes us shudder when we encounter Kranichfeld’s images.