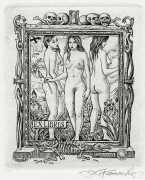

The first known bookplates or ex libris – a Latin phrase meaning ‘from the library of’ – are woodcuts from the fifteenth century, displaying the owner’s name and coat of arms. Through the centuries ex libris designers came up with ever more artful and imaginative designs for their clients’ libraries, inspiring a mania for collecting bookplates which lasted from the final quarter of the nineteenth century until the 1930s.

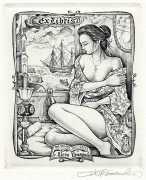

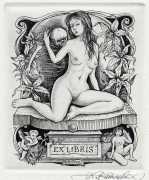

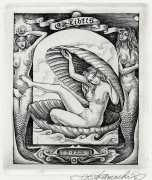

Today ex libris are once again in demand, eagerly sought by specialised collectors, and there are websites, fairs and exhibitions dedicated to the artform. Many plates are now produced as signed and numbered small format fine art prints, known as ‘free’ ex libris, never intended to be glued inside books but instead to be framed and displayed in the library of the client fortunate enough to be able to afford to commission it.

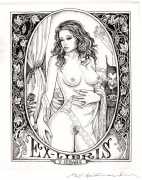

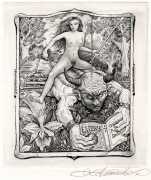

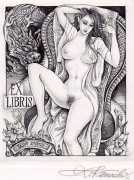

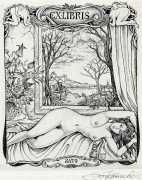

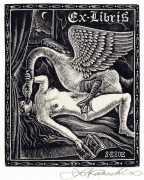

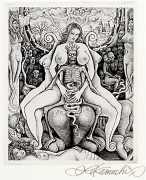

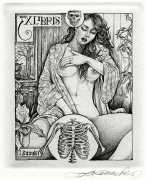

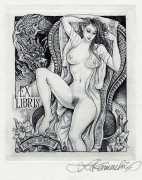

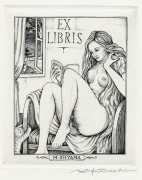

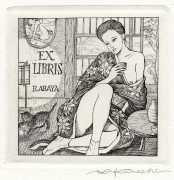

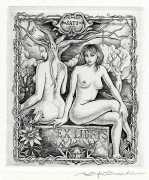

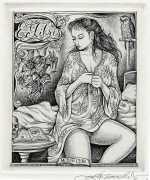

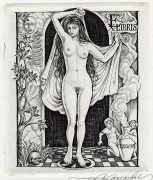

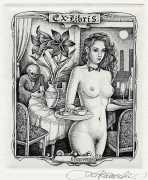

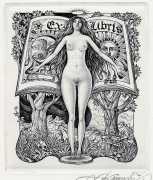

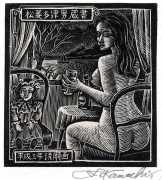

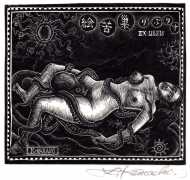

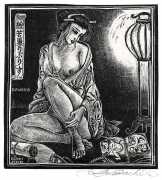

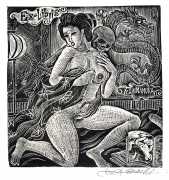

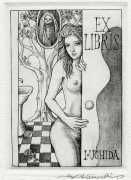

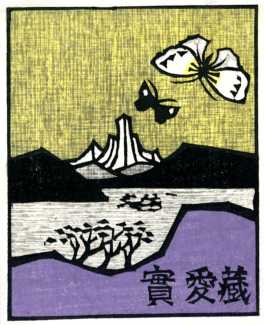

In recent years there has been a definite trend towards erotic subjects for bookplates, partly a throwback to the 1920s and 30s and partly to explore the potential of engraving techniques; it seems a pity that the high-quality results do not extend to more book illustration. In Japan, artists began to produce commissioned bookplates for book collectors in the 1950s, mostly using woodblocks in a simple range of colours, employing both representational and abstract imagery. The Nippon Exlibris Association was founded in 1957 to encourage interest in the art form.

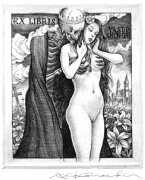

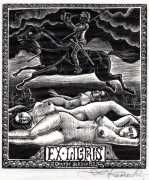

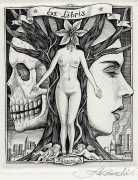

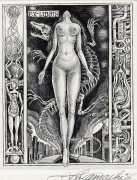

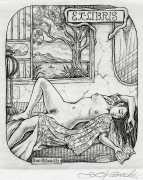

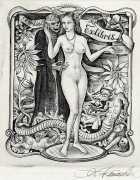

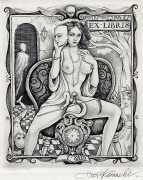

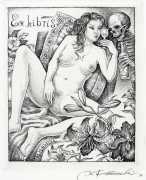

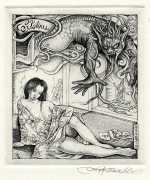

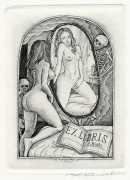

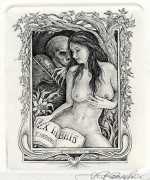

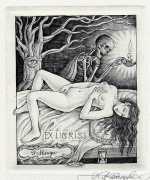

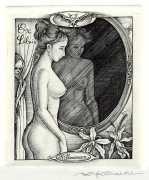

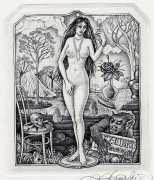

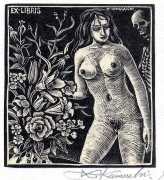

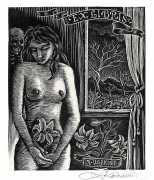

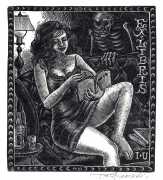

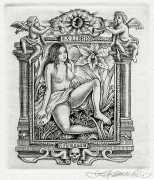

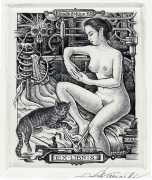

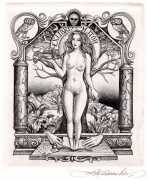

For his bookplates, Seiji Kamachi exclusively uses the traditional technique of copperplate etching, producing highly-detailed miniatures with a wealth of figurative and symbolic detail. All his bookplates feature naked young women, and most an intimation of mortality in the form of a skeleton, a skull, or the words ‘memento mori’ (‘Remember that you will die’ in Latin). While their collectors have a limited lifespan, both books and bookplates will almost certainly outlive them.