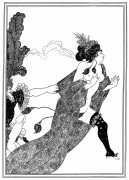

First performed in Athens in 411BC, Greek playwright Aristophanes’ best-known play is about Lysistrata’s extraordinary mission to end the Peloponnesian War. She persuades the women of Greece to withhold sexual privileges from their husbands and lovers as a means of forcing the men to negotiate peace. All does not go according to plan, but the play is notable for being an early exploration of sexual relations in a male-dominated society.

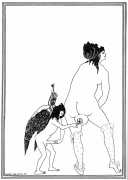

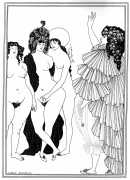

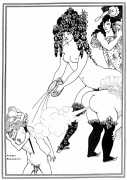

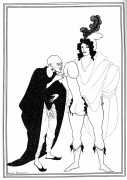

It was Beardsley’s publisher Leonard Smithers who suggested that he might illustrate the play, and the subject matter proved perfect for the artist’s inventiveness; the eight drawings were published by Smithers in a tiny edition of just one hundred copies. Though Beardsley wrote from his deathbed that he wanted all trace of the Lysistrata drawings destroyed, demonstrating the ambivalence he held for having been so daring, it is clear that they provided the perfect opportunity for him to engage all his creative and imaginative powers.

In Brigid Brophy’s 1968 biography Black and White: A Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley, she explores Aubrey Beardsley’s fascination with sex, and probably comes as close to an accurate analysis as is possible. ‘His vision,’ she writes, ‘is permanently that of a child lying in bed watching his mother dress for a dinner-party. His fantasy hangs this here, tries the effect of that there: everything is a jewel, and everything is a sexual organ. He is allured, yet afraid to touch: driven back on a cold minuteness of detailed attention, and yet passionately curious, with the emotional and involved curiosity children give to sex. The very fastidiousness of his line demonstrates the importance of touching and the fear that has to be overcome in order to do it. The child’s protest against his inexperience, against the ban on touching, is to glory in his ignorance. He does not know which sexual organs are appropriate to which sex; he makes deliberate howlers in order to howl against his exclusion from adult knowledge.’

Particularly in relation to the Lysistrata drawings, she continues ‘His depictions of women are deeply defiant of sexual classification: are they female fops, these personages of Beardsley’s, female dandies, female effeminates, even? Or are they male hoydens, male tomboys, boy butches?’ Whatever the truth, Aubrey Beardsley’s images presage and inform the exploration of gender boundaries both then and now.