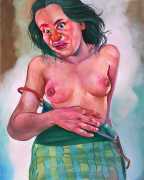

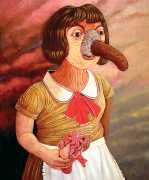

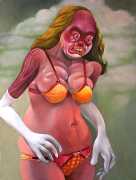

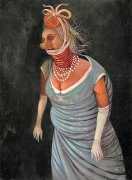

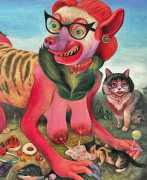

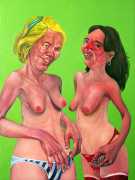

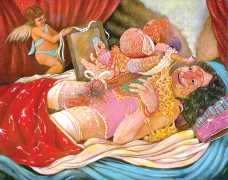

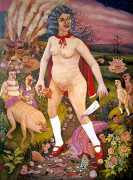

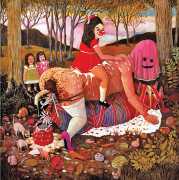

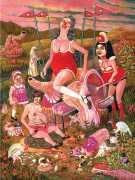

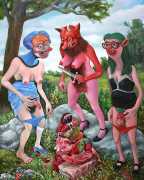

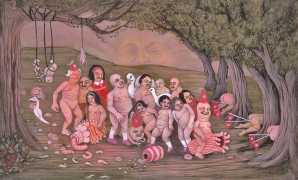

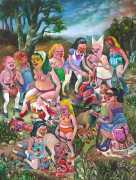

Gregory Jabobsen’s paintings are often described as grotesque, which he has no problem with. ‘I try to start painting nice people, with regular features. Then I look at it and it doesn't have the emotional impact I want, so I have to go in and scratch out their nose, and mess their face up a bit. It might be a sort of expressionism, a way of conveying intense emotion, like the peak of climax or the moment before death. There’s also a pathetic quality – for me sex ties in with being rather pathetic. I mean, sex is really silly; it’s mostly just thump-thump-thump. But I would love to paint beautiful people and still maintain that tension, like Balthus.’

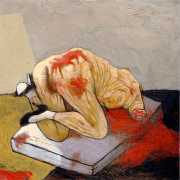

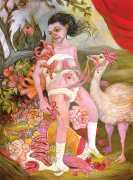

Medieval painting is a big influence on Jacobsen’s work. As he explains, ‘the characters have these looks on their faces that are really timeless, especially when something really awful is happening, they’re being boiled in a pot and are just staring off into space. I often see people with that idiotic, glazed look in their eyes. Painting faces is very hard for me. It's really easy to do a cute face or an ugly face, but I want to give it a certain quality of helplessness and agony, and then slap a moronic smile on it. Birds’ eyes are great; they have this ridiculous vacancy about them. I could watch pigeons all day; they make me laugh. But Bosch’s faces are amazing, and what the characters are doing even more so.’

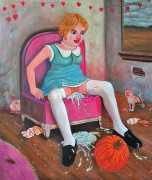

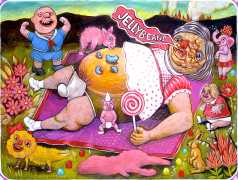

There is often a tendency to use artwork to read into an artist’s identity, to psychoanalyse them, and Jacobsen’s work is particularly susceptible to such a tendency. He rejects this approach out of hand: ‘I just don’t buy into that sort of reading. Certainly everything of me, my likes and dislikes, are in these paintings, but to actually psychoanalyse them is to pretty much just write them off. The childlike motifs are certainly not a nostalgia for childhood, because childhood was shit. I don't remember ever being innocent, and I’m sure no one else does. The figures wear this silly little underwear because it makes them look even more ridiculous. Most people are overgrown children. Just because I have obsessions about certain things doesn’t mean they rule my life. I’m obsessed with little-girl dresses with the Peter Pan collars, polka-dots and stripes, Mary Jane shoes, big noses, eggs, asses, moulded gelatin, mannequins with crudely painted eyes, Daleks from Dr Who, ramshackle contraptions on wheels. To try and understand what they all mean is futile.’