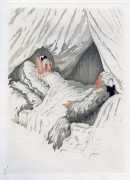

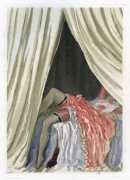

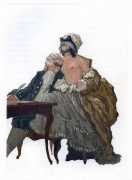

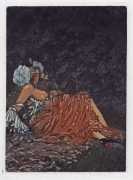

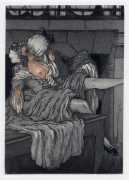

This early 1930s edition from the famous Paris publishing house of Briffaut brings together an important section from Restif de la Bretonne’s Monsieur Nicolas and an illustrator exploring a suitable style for the eighteenth century text. The result is mixed; Girard’s successful treatment of the textures of period fabrics and hangings is not matched by faces and red-tipped breasts which all look identical. Some of the compositions, though, work well, especially the darker, more brooding scenes.

This early 1930s edition from the famous Paris publishing house of Briffaut brings together an important section from Restif de la Bretonne’s Monsieur Nicolas and an illustrator exploring a suitable style for the eighteenth century text. The result is mixed; Girard’s successful treatment of the textures of period fabrics and hangings is not matched by faces and red-tipped breasts which all look identical. Some of the compositions, though, work well, especially the darker, more brooding scenes.

Collette Parangon was the heroine of Restif’s massive autobiographical novel, and one of the things he loved most about her was her dainty feet, which explains why Restif de la Bretonne is popularly identified as history’s foot-fetishist par excellence.

Here is the passage from Volume 5 of Havelock Ellis’s monumental Studies in the Psychology which cemented Restif’s fetishist reputation.

Perhaps the chief passion of Restif’s life was his love for Colette Parangon. He was still a boy, she was the young and virtuous wife of the printer whose apprentice Restif was and in whose house he lived. Madame Parangon, a charming woman, as she is described, was not happily married, and she evidently felt a tender affection for the boy whose excessive love and reverence for her were not always successfully concealed. ‘Madonna Parangon,’ he tells us, ‘possessed a charm which I could never resist, a pretty little foot; it is a charm which arouses more than tenderness. Her shoes, made in Paris, had that voluptuous elegance which seems to communicate soul and life. Sometimes Colette wore shoes of simple white drugget or with silver flowers; sometimes rose-colored slippers with green heels, or green with rose heels; her supple feet, far from deforming her shoes, increased their grace and rendered the form more exciting.’ One day, on entering the house, he saw Madame Parangon elegantly dressed and wearing rose-colored shoes with tongues, and with green heels and a pretty rosette. They were new and she took them off to put on green slippers with rose heels and borders which he thought equally exciting. As soon as she had left the room, he continues, ‘carried away by the most impetuous passion and idolizing Colette, I seemed to see her and touch her in handling what she had just worn; my lips pressed one of these jewels, while the other, deceiving the sacred end of nature, from excess of exaltation replaced the object of sex (I cannot express myself more clearly). The warmth which she had communicated to the insensible object which had touched her still remained and gave a soul to it; a voluptuous cloud covered my eyes.’ He adds that he would kiss with rage and transport whatever had come in close contact with the woman he adored, and on one occasion eagerly pressed his lips to her cast-off underlinen. At this period Restif’s foot-fetishism reached its highest point of development. It was the aberration of a highly sensitive and very precocious boy. While the preoccupation with feet and shoes persisted throughout life, it never became a complete perversion and never replaced the normal end of sexual desire. His love for Madam Parangon, one of the deepest emotions in his whole life, was also the climax of his shoe-fetishism. She represented his ideal woman, an ethereal sylph with wasp-waist and a child’s feet; it was always his highest praise for a woman that she resembled Madame Parangon, and he desired that her slipper should be buried with him.