The enterprising and courageous French publisher Jean-Jacques Pauvert, notable for publishing the work of the Marquis de Sade in the early 1950s and as the first publisher of the Story of O in 1954, said of Le con d’Irène (Irene’s Cunt) that it is ‘one of the four or five finest poetic texts ever produced by surrealism’, and that ‘there are few books for which I have so much desired, with the full force of desire, to be the publisher; most of the others have ended up in my catalogue, but this one never will be.’ Others agreed; the writer and critic Jean Paulhan considered the work a masterpiece of the genre, and Albert Camus thought it the best text he had ever read relating to eroticism.

The enterprising and courageous French publisher Jean-Jacques Pauvert, notable for publishing the work of the Marquis de Sade in the early 1950s and as the first publisher of the Story of O in 1954, said of Le con d’Irène (Irene’s Cunt) that it is ‘one of the four or five finest poetic texts ever produced by surrealism’, and that ‘there are few books for which I have so much desired, with the full force of desire, to be the publisher; most of the others have ended up in my catalogue, but this one never will be.’ Others agreed; the writer and critic Jean Paulhan considered the work a masterpiece of the genre, and Albert Camus thought it the best text he had ever read relating to eroticism.

A flavour of the text: ‘She believes without much effort that love is not different from its object, that there is nothing else to look for. She can say it in an unpleasant, direct way. She knows how to be rude and precise. Words make her no more afraid than men do, and like them they sometimes make her happy. She never deprives herself of words even in the midst of her seductiveness. They come out of her then without any effort, in all their violence. Ah, what language she can speak. She warms herself, and her lover, with a burning and ignoble vocabulary. She rolls in words like a sweat. It is quite something to love Irène.’

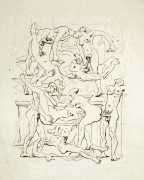

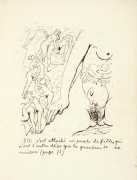

Le con d’Irène was published with no indication of author, illustrator or publisher, in an edition of just 150 numbered copies, and as no new edition appeared for another twenty-five years it became the subject of much mystery and rarity. The five illustrations were claimed by André Masson as his work, but the book’s authorship was the subject of much debate and conjecture. Those in the know were aware of exactly who had written it – Louis Aragon, one of the leading voices of the surrealist movement in France, co-founder with André Breton and Philippe Soupault of the surrealist review Litérature, and long-time member of the French Communist Party. Yet Aragon died denying that he was the book’s author, which is why it took until 1952 before a second edition appeared, and also why, having an ‘anonymous author’, the book was officially banned by the French censors as late as 1968.

The 1952 limited edition, published by Cercle du livre précieux, replaced the Masson illustrations with a single engraving by Hans Bellmer and a preface by André Pleyre de Mandiargues, as did a 1968 reprint by L’or du temps. To overcome the problem of an ‘anonymous author’, the 1968 printing provided the pseudonym Albert de Routisie, which was also used in the (very good) 1969 Grove Press English translation by Lowell Blair. Both the 1968 French and 1969 American editions shortened the title to Irene, again to avoid the attention of the censors.

We have said very little about the Masson illustrations; Masson knew Aragon and must have read Irène in manuscript. The five drawings, which are both highly explicit and relate directly to passages in the text, are among his earliest in the free surrealist style that he was to make his trademark.

For those who like a detective story with an erotic twist, here is the final chapter of the story of Louis Aragon and Le con d’Irene, as told by Jérôme Dupuis in the French newspaper l’Express in July 2008.

Before becoming the official mouthpiece of the French Communist Party, Louis Aragon produced a masterpiece of erotic literature, a secret he kept until his death. Right up to his last breath in 1982, he fiercely contested the author of the mysterious Con d’Irene, forbidding any publisher to put his name to a text which brands society as a brothel. No, a thousand times no, he had nothing to do with the voluptuous Irène, ‘born of the storm’.

To understand what actually happened we must go back to the 1920s. Louis Aragon, a surrealist poet without a penny to his name, formed a friendship with Jacques Doucet, elegant couturier of the belle epoque and patron of the arts. The two men signed a strange pact – for a monthly payment of 1,000 francs, the poet would send his latest manuscripts to the couturier. And so during the 1926 Aragon sent instalments of an ambitious project, La défense de l’infini. A section of this work was called Le con d’Irène.

But who is this mysterious Irène, the heroine of this erotic text? As always with Aragon, we must plunge into his unhappy love affairs. First there was Eyre de Lanux, an American designer who decided that she preferred Drieu la Rochelle. The poet, desperate, consoled himself with Denise Levy, who went off and married another of his friends, Pierre Naville. These two women both figured heavily in the character of Irène.

But there was a third muse whose shadow hovered over the fate of Irène’s con: Nancy Cunard. This rich American woman, also close to James Joyce, became Aragon’s lover in 1926. Thanks to her fortune the couple crisscrossed Europe until one fatal day in November 1927 when, in a gesture of unexplained despair, in the fireplace of their room in the Hotel de la Puerta del Sol in Madrid, Aragon burned the 1,500 sheets of La défense de l’infinite. Nancy Cunard managed to save an armful of sheets of this auto-da-fé. A year later in Venice, no longer Nancy Cunard’s gigolo, Louis Aragon tried to commit suicide.

Abandoned by his two patrons, Doucet and Cunard, the poet had lost all sources of income. Is this why he decided to publish Le con d’Irène? He entrusted the manuscript to the young Pascal Pia, who printed it with the help of a specialist in clandestine publications, René Bonnel. Enhanced with five etchings by André Masson, the typography of the title page elegantly depicting the female sex, the book was published in April 1928 – without an author’s name. Aragon’s surrealist friends knew of course – Simone Breton, the wife of the author of the surrealist manifesto, ordered one of the luxury copies, but officially Aragon claims that he had nothing to do with the text, that he would not have compromised himself with such a ‘bourgeois’ novel.

In reality, the explanation is to be found in the field of politics. ‘His proximity to the Communist Party narrowed his options, and the readers of L’humanité would not have appreciated knowing that he was the author of this sulphurous text,’ explains Lionel Follet, editor of the most complete edition of Con d’Irène. And so the ‘official’ poet of the Communist Party preferred to be celebrated for his more political works, like the 1963 Le fou d’Elsa (The Fool of Elsa), than for Le con d’Irène.

This is the position Louis Aragon maintained until his death. He told his friends ‘I swore to an investigating judge in the 1930s that I was not the author of this text, and once you have lied to a judge you can never change your story.’

But then begins the astonishing posthumous career of the Con d’Irène. Aragon had forbidden his archives to be consulted during his lifetime, but in 1982 the embargo was lifted. In 1989, while a lecturer at the Faculty of Arts in Besançon, Lionel Follet had the idea of searching the archives of the Humanities Research Center in Austin, where the archives of Nancy Cunard had ended up. There he found the pages which Cunard had saved from the Madrid auto-da-fé, torn, charred and stuck together with tape, but unmistakably Irène.

And so to the Paris auction room of the Salle Drouot, on 2nd December 1993, where the collection of the famous bookseller Jacques Matarasso was being sold. Included was the copy of Le con d’Irène that had belonged to Pascal Pia. At the end of the book were the proofs of the text – corrected by Aragon’s own hand! The bidding ended at 220,000 francs (33,000 euros), and after the hammer had fallen it became clear that the buyer was the National Library of France, the very authority that had attempted and failed to ban the book in 1968. What sweet justice.