Andy Warhol studied commercial art at the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1949. There, he learned foundational skills in drawing, design and illustration, which shaped his early career as a successful commercial illustrator in New York.

After graduating, Warhol moved to New York City later in 1949, and began working in advertising and magazine illustration. While he did not attend further formal art school after Carnegie, his time in New York involved extensive informal training through immersion in the city’s art scene, galleries, and collaborations with other artists.

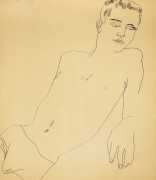

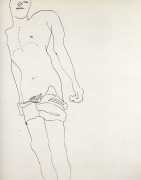

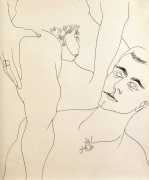

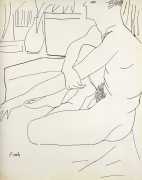

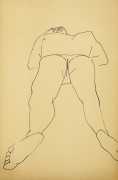

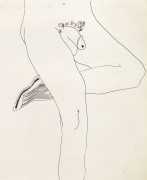

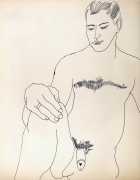

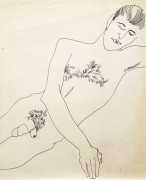

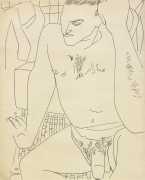

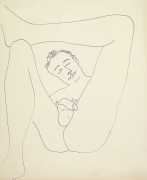

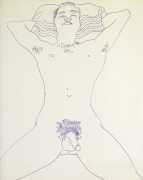

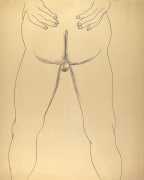

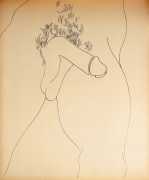

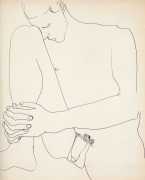

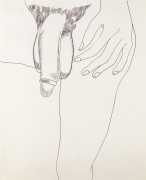

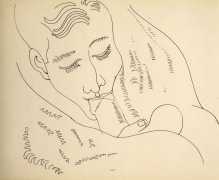

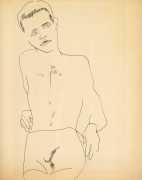

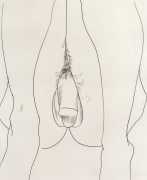

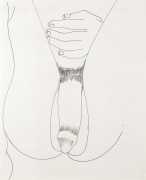

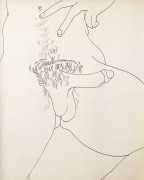

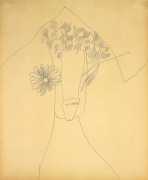

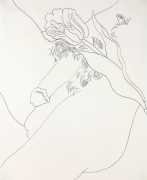

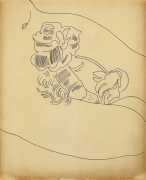

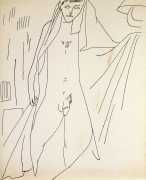

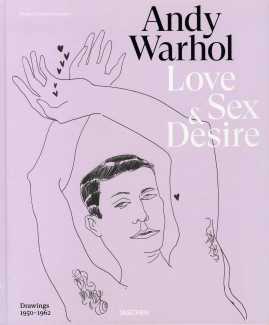

It was in New York that he felt able to explore his homosexuality more freely, and turned his artistic skills to an impressive portfolio of drawings of naked men, both lovers and friends. In 2020 the publisher Taschen produced a curated collection of these drawings, titled Love, Sex and Desire: Drawings 1950–1962, with more than three hundred drawings, together with an introduction by the Warhol Foundation’s Michael Dayton Hermann, and essays by Warhol biographer Blake Gopnik and art critic Drew Zeiba.

Here is Hermann’s perceptive introduction, entitled ‘Love is Love’.

Here is Hermann’s perceptive introduction, entitled ‘Love is Love’.

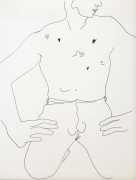

The intoxicating thrill of falling in love blinds us to the fact that it is a perishable gift existing for a brief period. In the moment, we can’t imagine it will end. During these spells, we are full of hope and dismissive of reason, as our unbridled emotions lift the weight of everyday reality. This delight leaves an indelible mark on our souls. From Shakespeare to Bernini to Oscar Wilde, writers, poets, and artists have long celebrated this blissfully mad sensation through ambitious works which continue to inspire us by powerfully conveying universal themes. However, if you look around, you will witness this sublime emotion in the most ordinary expressions, from a caring glance between strangers to a gentle kiss shared by lovers. These simple moments, like some of those captured in Andy Warhol’s intimate drawings of men from the 1950s, remind us of the splendours life has to offer. A heart escaping from pursed lips, nude bodies sharing a rapturous embrace, or a lustful stare are just a few examples of the simple, whimsical, and affectionate moments Warhol captured in these drawings of love, sex, and desire.

Early in my career, I had the privilege of working closely with the vast collection of original works at The Andy Warhol Foundation. Ever curious, I indulged myself in browsing the flat files in the art-storage warehouse whenever I could. I embraced it all – whether Warhol’s colours overwhelmed my senses, or his pungent Oxidation paintings made me wish I had no sense of smell at all. After casually glimpsing several drawings of men from the 1950s, I found myself examining dozens, and then, before I knew it, I was mesmerised by hundreds of them. While they are aesthetically pleasing and well executed, in recognising their multitude I realised these drawings are an early example of Warhol obsessively capturing people and moments, as he would later do with his Polaroid and 35mm cameras, tape recorder, and diaries. However, these hand-drawn, private moments filled with sexual radiation are distinct, because they are imbued with an emotional vulnerability that few of his later works exhibit. These early works showcase Warhol’s own hand and reveal an artist who mindfully crafted an impenetrable public image for himself. After all, this is someone who characterised himself as a deeply superficial person and declared he wanted to be a machine and create works which were machinelike. Collectively, the hundreds of drawings Warhol made from life during this period provide a touching portrait of the one person not depicted in any of them – Andy Warhol.

Warhol’s drawings of men depict a spectrum of intimacy from a yearning gaze to a loving embrace to fellatio. That these works were created by a practicing Catholic in the United States at a time when sodomy was a harshly punished felony in every state illustrates that, even at a young age, Warhol embraced the role of the nonconformist. Within this context of institutionalised oppression, Warhol publicly displayed some of these drawings at the Bodley Gallery in 1956 in his exhibition Studies for a Boy Book. John Giorno, artist, poet, and Warhol’s former lover, explained, ‘Andy was a gay man, and worked with the homoerotic. In the homophobic 1950s, this was daring and heroic. A great risk.’ Publicly countering the socially acceptable ideas of sexuality, Warhol did not intend to ingratiate himself into powerful social circles but instead expected the circumference of those elite groups to expand to be more inclusive of marginalised people like himself.

Even in 1952, four years prior to his Bodley Gallery exhibition, Warhol bravely aligned himself with queer culture when he celebrated the gay literary icon Truman Capote with an exhibition of drawings based on Capote’s writings. Warhol befriended many other writers and collaborated with a number of poets on projects, pairing his visual art with their prose, from books with Ralph Pomeroy to collaborations with Gerard Malanga, Nico, and Walasse Ting. Poets, like visual artists, have a knack for distilling complex ideas to their essence. Warhol, with his confident hand, accomplished his own such distillation in these tender drawings, which communicate numerous themes. Given the breadth and depth of these works, and inspired by Warhol’s prior collaborations with poets, this book is organised around poems by authors who were contemporaries of Warhol and similarly unapologetic in their positive celebrations of love, sex, and desire among men, in spite of societal taboos.

Warhol’s drawings of men remain widely seductive many decades after their creation. They render the intoxicating thrill of love, sex, and desire, irrespective of the specific identities of the viewer or the beloved. As Warhol later said about his storied studio, The Factory, which brought together colourful characters regardless of their social status or sexuality, ‘People weren’t particularly interested in seeing me, they were interested in seeing each other.’ Warhol brought disparate people together in ways that focused on their similarities rather than their differences. In these captivating early drawings we not only see a multitude of people pulled into Warhol’s orbit, but we also see Warhol reveal himself through delicate works which celebrate the power of love, sex, and desire as he experienced them. I like to think we can now recognise that the works of art reproduced here have always figuratively stood on a pedestal inscribed ‘Love is love’.