Andy Warhol is best known for his iconic pop art – images of Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles – but he also explored eroticism throughout his career, especially in his early and lesser-known works. Understanding Warhol as an erotic artist involves looking at his work through a more intimate, queer, and often private lens, diverging from the polished commercial persona he is usually associated with.

Andy Warhol is best known for his iconic pop art – images of Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles – but he also explored eroticism throughout his career, especially in his early and lesser-known works. Understanding Warhol as an erotic artist involves looking at his work through a more intimate, queer, and often private lens, diverging from the polished commercial persona he is usually associated with.

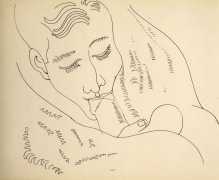

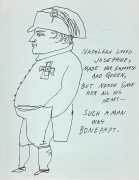

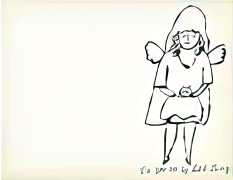

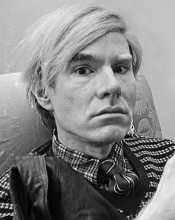

Warhol’s erotic art is inseparable from his biography, particularly his experience of queerness, secrecy and self-fashioning in mid-twentieth-century America. Born in 1928 to a working-class Slovak immigrant family in Pittsburgh, Warhol grew up Catholic, physically fragile and socially marginal conditions which fostered both acute self-awareness and a retreat into fantasy and observation. These traits profoundly shaped the tone of his erotic work, which tends toward longing, voyeurism and stylisation rather than overt sexual assertion.

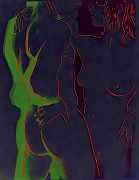

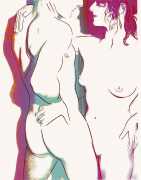

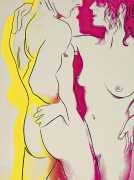

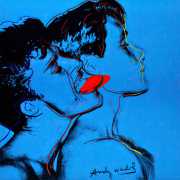

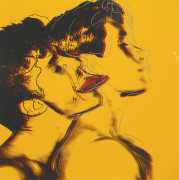

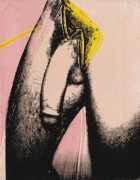

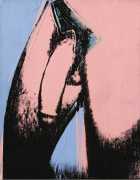

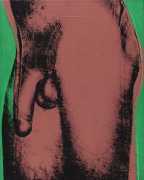

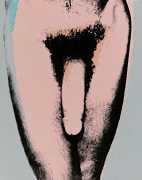

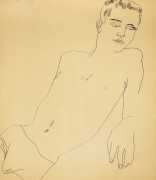

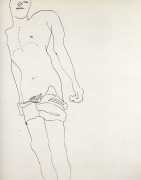

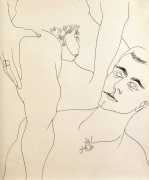

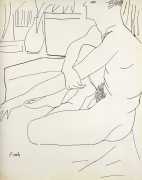

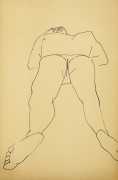

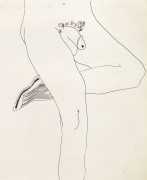

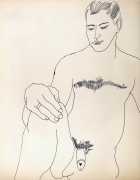

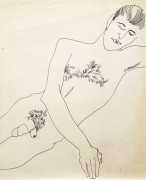

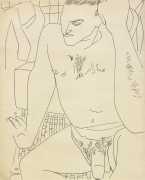

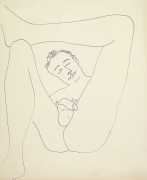

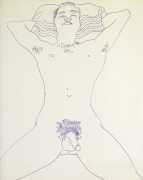

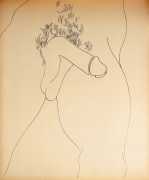

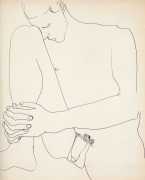

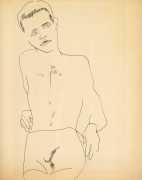

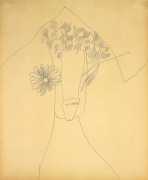

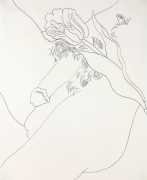

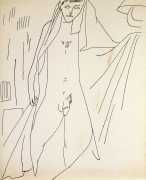

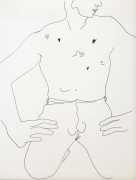

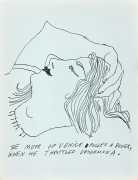

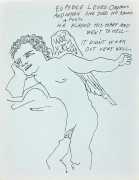

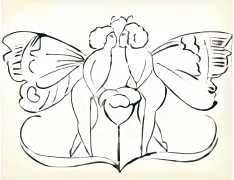

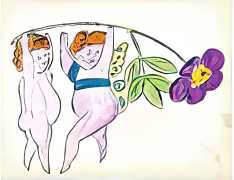

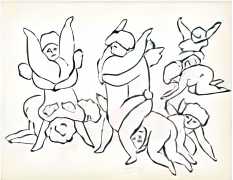

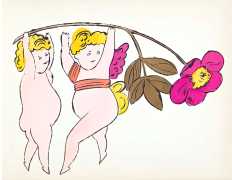

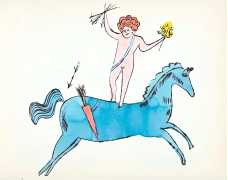

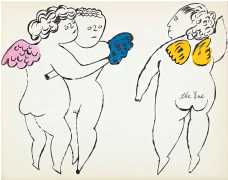

In the 1950s, before becoming a pop art icon, Warhol produced a large number of erotic drawings, particularly of male nudes. These works were often tender, sensual, and unabashedly homoerotic. They were made during a time when open expressions of homosexuality were taboo and even criminalised. Warhol’s early drawings depict male figures in intimate, affectionate, and sexual poses, often with a delicate, almost whimsical line.

Much of Warhol's eroticism is tied to his queer identity, which was expressed subtly in his public persona and more explicitly in his art. While he often maintained a certain aloofness or detachment in interviews, his work suggests a deep engagement with desire, power and queer experience. His art is closely bound to the structure of his intimate relationships, which were often asymmetrical, mediated, and marked by emotional distance. Rather than forming stable romantic partnerships, he tended to attach himself to muses, protégés, or objects of fascination – men such as Edward Wallowitch, John Giorno, Jed Johnson, or later Jon Gould and Jean-Michel Basquiat. These relationships frequently involved admiration, dependency or caretaking rather than mutual erotic fulfilment. Warhol was often the watcher, the manager, the archivist of desire, a pattern that translated directly into his erotic imagery.

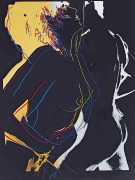

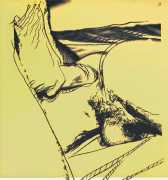

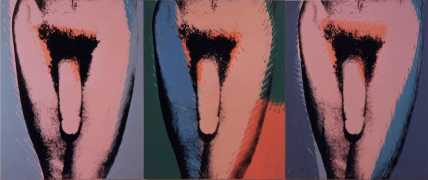

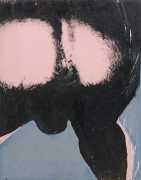

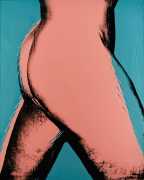

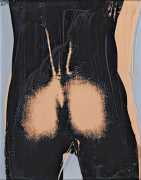

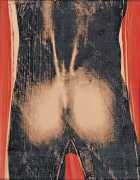

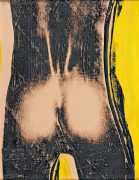

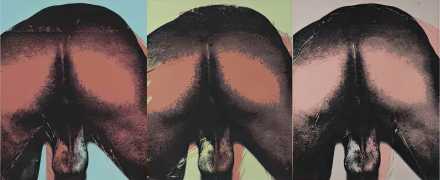

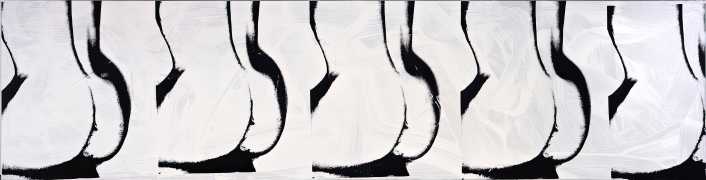

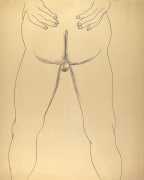

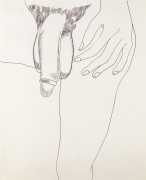

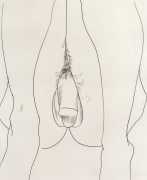

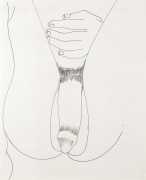

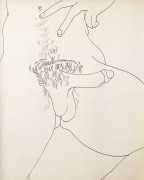

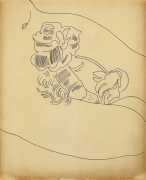

This dynamic intensified after the radical feminist Valerie Solanas shot Warhol in 1968. The attack nearly killed him, and left him permanently physically fragile, dependent on medical corsets, and deeply fearful of bodily invasion. Psychologically it reinforced his instinct to retreat. After 1968 intimacy became more dangerous, and the eroticism in his art hardened into repetition and detachment. The explicit drawings and photographs of the 1970s, including Sex Parts, Torso, and Ladies and Gentlemen – are impersonal and curiously affectless, presenting sex as data rather than as encounter.