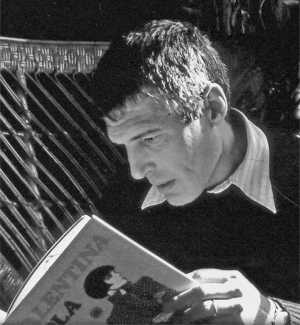

Guido Crepax, christened Guido Crepas, grew up in Milan in northern Italy. As a child he loved drawing, and during the war years while taking shelter with his family in Venice copied American comics and created characters of his own. After the war he studied architecture at the University of Milan, and after graduating produced publicity material for companies including Shell, Dunlop, Terital and Fujica, illustrated book covers and record sleeves, particularly for jazz recordings, and contributed illustrations to the medical journal Tempo Medico.

Guido Crepax, christened Guido Crepas, grew up in Milan in northern Italy. As a child he loved drawing, and during the war years while taking shelter with his family in Venice copied American comics and created characters of his own. After the war he studied architecture at the University of Milan, and after graduating produced publicity material for companies including Shell, Dunlop, Terital and Fujica, illustrated book covers and record sleeves, particularly for jazz recordings, and contributed illustrations to the medical journal Tempo Medico.

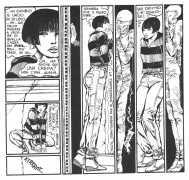

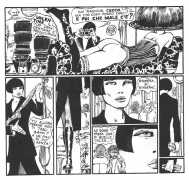

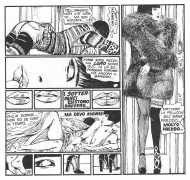

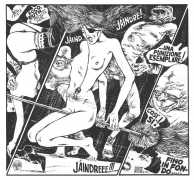

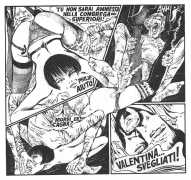

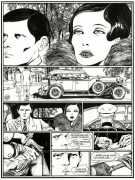

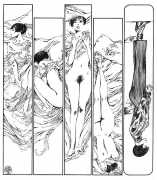

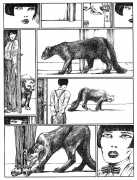

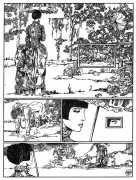

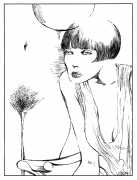

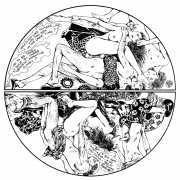

He made his debut in comics in 1959, and in 1965 joined the team at the magazine Linus, introducing a superhero called Neutron. His Neutron strip featured a minor character, a reporter and photographer called Valentina, who became the title character for whom Crepax is best known. From Valentina onwards Guido Crepax continued to draw naked young women, many of them inspired by the actress Louise Brooks, whom Crepax adored. His ever-growing audience loved both his erotic storylines and his graphic skills, and his fluent and intelligent narratives came to embrace characters of his own making and classic erotic stories like Sade’s Justine, Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs, and Pauline Réage’s Histoire d’O. The revolutions that Crepax brought to the comic book concerned not only style – his innovative viewpoints, with their implications of camera angle, and his varying of image-size – but also narrative perspective. ‘I’ve always been a little arrogant,’ he said in an interview, ‘which is why, in the 1960s, I told the publisher Gandini that I was going to do comic books that would be completely different. I wanted to prove that I could do one from scratch, without experience, and still make it better than traditional comics.’

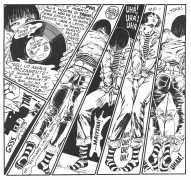

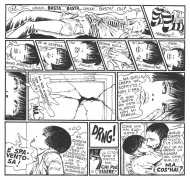

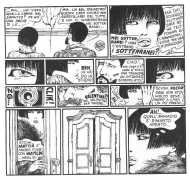

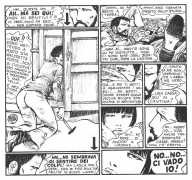

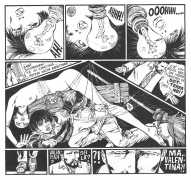

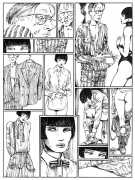

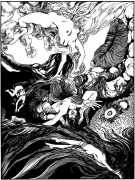

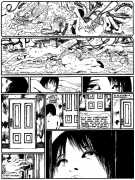

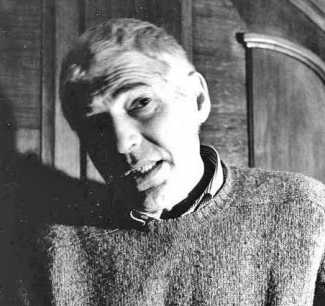

And so he developed his preference for disjointed narratives, in which the image is the vector of thought and all pretence of verbal logic is abandoned. Crepax stories are often difficult to follow at first; the architectonic connections are not always clearly conceived or fluently combined, and their unsystematic deployment often yields no overt plot-line. Eminent semioticians, such as Crepax’s friend Umberto Eco, have concluded that ‘You draw beautifully, but you should find an author to write your stories’. Unlike many comic artists, he appears to have few young followers; there is no ‘Crepax tradition’. As he says, ‘my way of telling stories is so remote from tradition that young artists – rightly, I confess – choose other models. I have no desire to serve as a model. My universe is truly my own.’

And so he developed his preference for disjointed narratives, in which the image is the vector of thought and all pretence of verbal logic is abandoned. Crepax stories are often difficult to follow at first; the architectonic connections are not always clearly conceived or fluently combined, and their unsystematic deployment often yields no overt plot-line. Eminent semioticians, such as Crepax’s friend Umberto Eco, have concluded that ‘You draw beautifully, but you should find an author to write your stories’. Unlike many comic artists, he appears to have few young followers; there is no ‘Crepax tradition’. As he says, ‘my way of telling stories is so remote from tradition that young artists – rightly, I confess – choose other models. I have no desire to serve as a model. My universe is truly my own.’

The following text, reproduced with thanks, is by Stefan Prince, from an article written in the spring of 2000 and published in Skin Two magazine #33. It sums up many of the important aspects of Crepax’s work.

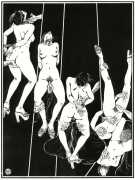

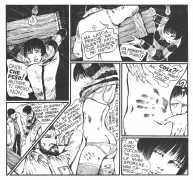

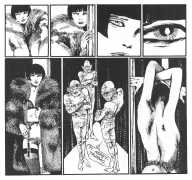

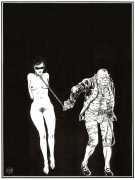

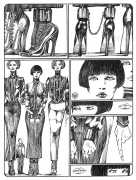

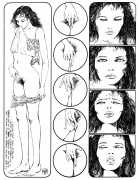

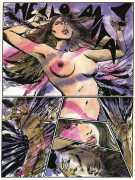

Acknowledging the daring nature of his comics, Crepax maintains that his adult audience must be capable of seizing the ambiguities behind appearances, distinguishing the true fantasies from stark reality. ‘So if I have drawn whips, chains, bonds of every kind,’ he says, ‘even if I have reproduced in my pictures the most audacious bold erotic perversions, I, in fact, hate violence and lack of respect towards oneself and to others, and all forms of excess. The extraordinary things that my poor young girls in love undergo – Valentina, and Bianca, Anita and Justine, Emmanuelle and Madame O – have nothing to do with the treatises on sexual psychopathology of Richard von Krafft-Ebing: they are only visionary exercises, imaginary madness transferred onto paper, deliriums, desires ruled by a purely cerebral mechanism. What interests me more than anything else is that the game never becomes obscene, that it is never trapped by vulgarity. Have a look at them, the girls on display; however they might be bound, frustrated, constrained, imprisoned, compressed or struck, there is never one single drop of blood. The blow on their skins in the end never leaves more of a mark than a firm embrace.’

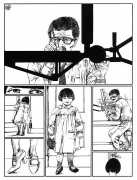

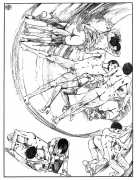

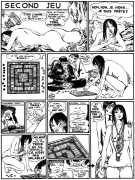

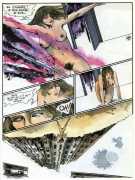

The erotic intrigues and embraces which torment Valentina are of course, by necessity, almost always nothing more than dreams, oneiric projections, surreal adventures beyond the real. Sometimes her son Matia’s comic books are a starting point for a daydream adventure. In one tale Crepax pays homage to his mentors by portraying Valentina in the style of Hugo Pratt, Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, Stan Lee, and even John Willie, and introduces the comic book heroes of his childhood, Dick Tracy, Tarzan, Prince Valiant and Mandrake, into the storyline. Time and again Crepax reinvents the layout of his page, and in storyboard fashion the pictures tell the story almost to the exclusion of traditional balloon-enclosed dialogue. In the Valentina story Lanterna Magica dialogue is dispensed with altogether.

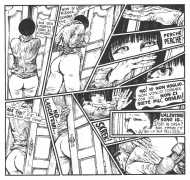

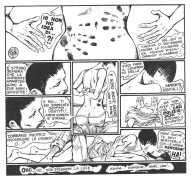

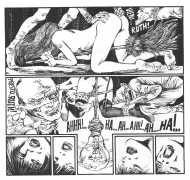

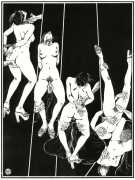

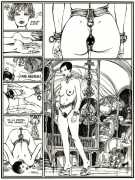

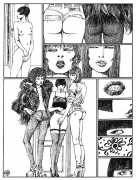

It could be said that Valentina, described by Graziano Frediani as ‘the allegory of a need, a mirror in fragments, the mark left from a laceration’, has in Crepax’s Story of O become Madam O, the plaything of the valets and members of the Roissy mansion, of her lover René who takes her there, and of Sir Stephen who claims ownership by having O branded with his initials. The story unfolds like an adult fairy tale, familiar territory for Crepax. With consummate skill, he takes every opportunity presented by this sadomasochistic literary classic to busy his pages with all manner of menace, stylised violence, eroticism and sex. Whips, masks, erect penises, rounded breasts, and marked buttocks proliferate. Wilinsky, the French illustrator, said Crepax drew the best ass of any comic strip artist, and certainly that part of O’s anatomy comes in for its full share of cruel treatment in Story of O.

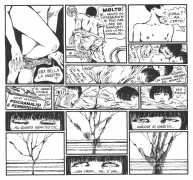

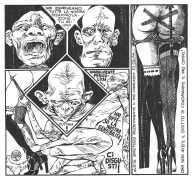

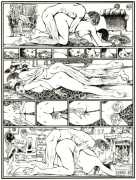

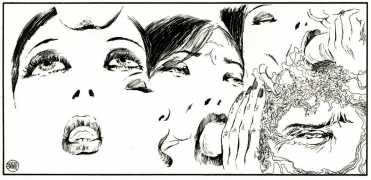

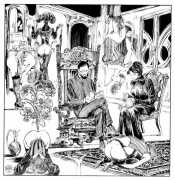

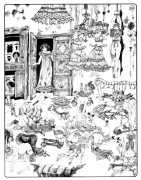

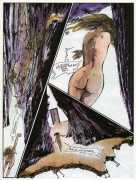

The critic Ghera has pointed out, ‘The body of O, in addition to the brutalised level of the narrative fable, is freely manipulated in accordance with a scheme which is obsessively geometrical: the heroine is often on her knees or displayed systematically at an angle, a square or another angle; or otherwise here the image is broken up into different parts as if it were pieces of mosaic,’ This mosaic is the ‘mirror in fragments’, and Crepax breaks down the narrative into little boxes in which we see the sphincter or the vagina or the open mouth of the heroine, forming a perfect ‘o’. But here and there this rigid geometry is under threat of collapse, of being sucked into some threatening void which is about to open up in the background, amongst the clutter of opulent furnishings, drapes or architecture.

We are reminded that the progression from Valentina, through Bianca, Anita, the ever more sophisticated Valentina, and eventually to Story of O, Emmanuelle, Sade’s Justine and Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs was inevitable. This ‘weaver of innocent plots’ is indeed, as Frediani describes Crepax, ‘a hunter of butterflies’. Crepax points out, ‘From the point of view of eroticism it’s the atmosphere, the situation, which gives the scene its eroticism’. Valentina, Bianca, O are the victims of the most barbaric treatment always amidst splendid and baroque backgrounds. Pursued through labyrinthian perils, raped, whipped, and entangled in all manner of bizarre Heath-Robinson-like torture machines, they always emerge, however, Phoenix-like from their ordeals.

As Paolo Caneppele and Gunter Krena note, ‘Ineffable as desire may be, it can nonetheless be represented’. Crepax leaves an indelible impression of desire. You either adore him or loathe him, but without a doubt there will never be another comic book artist quite like Guido Crepax.