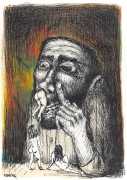

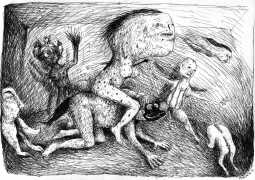

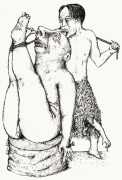

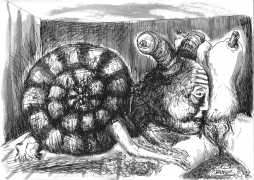

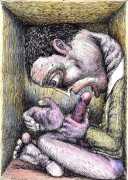

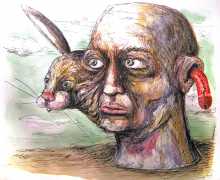

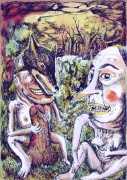

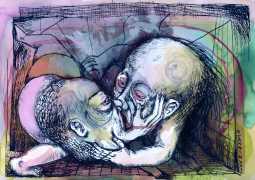

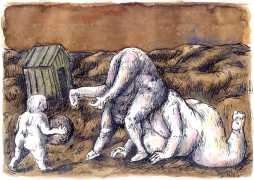

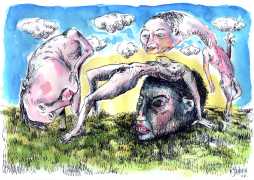

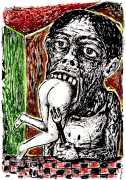

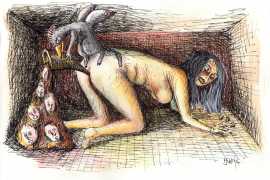

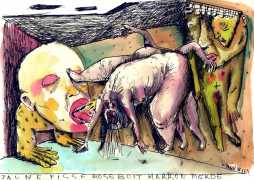

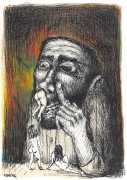

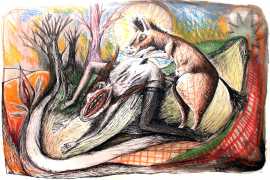

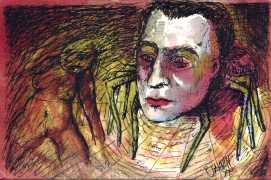

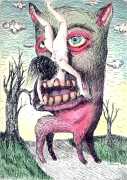

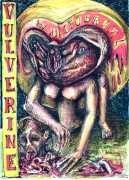

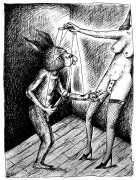

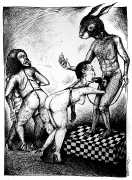

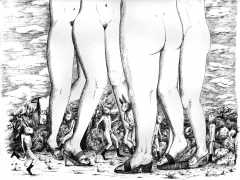

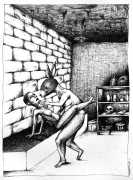

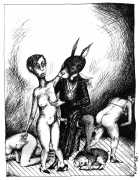

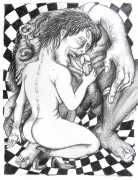

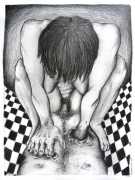

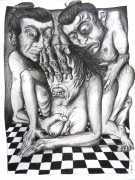

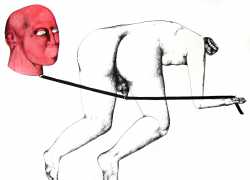

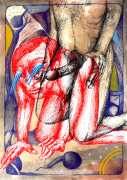

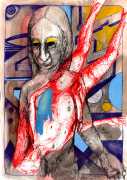

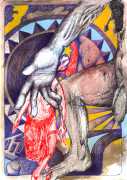

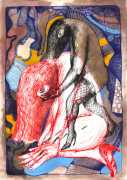

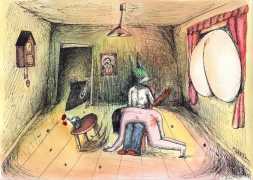

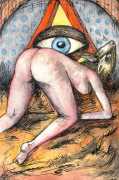

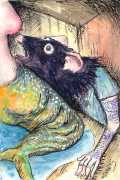

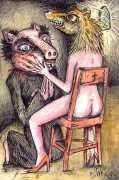

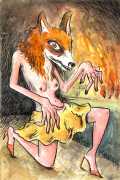

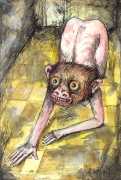

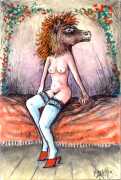

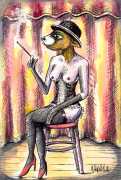

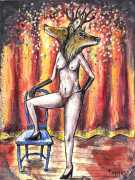

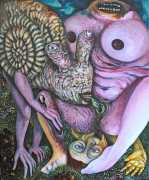

The French artist Patrick Jannin, with his disturbing images of creatures of startling beauty, women with animal heads, animals with dreamy bodies, goddesses straight out of ancient myths, reminds us that ugliness and beauty, baseness and the sublime, are never very far apart. As Frédéric-Charles Baitinger has written of Jannin’s work, ‘Jannin’s art is the expression of a soul having chosen to confront the conflicts it encounters, and to make this struggle the starting point of a work without ornament, of work that is absolutely honest.’

The French artist Patrick Jannin, with his disturbing images of creatures of startling beauty, women with animal heads, animals with dreamy bodies, goddesses straight out of ancient myths, reminds us that ugliness and beauty, baseness and the sublime, are never very far apart. As Frédéric-Charles Baitinger has written of Jannin’s work, ‘Jannin’s art is the expression of a soul having chosen to confront the conflicts it encounters, and to make this struggle the starting point of a work without ornament, of work that is absolutely honest.’

Much of Patrick Jannin’s work is what might conventionally be called erotic, but as with all his output the erotic, the sexual, never ignores the messiness, ambiguity and pain that inevitably exists alongside beauty, compassion and desire.

Here is Jannin in his own words:

I think it was to escape boredom that I started drawing. Coming from a family of three children, the other two nine and ten years older than me, when I was ten I found myself alone at home with my parents. We had just moved to the countryside, and I was bored. I didn’t really have any friends, sport didn’t interest me, and my classmates were all more stupid than each other, to say nothing of the teachers.

So I took refuge in books. We had a well-stocked library. Paperbacks from my grandparents, comics and novels from my brother and sister, a big red-covered encyclopedia in about fifteen volumes. I read everything that came to hand, I loved it. Thus I could go from Lucky Luke to the Métal Hurlant of my brother, then move on to a Simone de Beauvoir of my sister, to finish with a Daninos of my grandfather. I had access to everything. There were also some books my sister had found when we moved into an old house that had previously belonged to a doctor – books full of illustrations of monsters, deformed children, diseases. I glanced at them quickly, because they scared me, but I never really forgot them. This is perhaps where my way of drawing today, my taste for the bizarre and the grotesque, comes from.

I was around sixteen when my art became a little more serious. My sister, who also drew and owned a few works of art, gave me a box of oil pastels. It was the beginning of the eighties, in full punk era, and even in my backwater I was part of a gang. We drank, we got high, we scared each other, and above all we scared others. I drew more and more. I had made a comic strip about my buddies from boarding school and the streets, and my already crazy dreams had taken on another dimension with a lot of beer, solvents and hash. I was convinced that I had to smoke in order to be able to create. I would soon realise that, on the contrary, smoking was preventing me from giving free rein to my imagination.

From high school I went to university to study psychology. Madness fascinated me. I had discovered Lautréamont, and swore by him. To pay for my studies I started doing shifts in centres for the mentally handicapped. It wasn’t like in the books. Madness wasn’t beautiful. It smelled of piss and shit. I gave up my studies and worked some more in institutions, confronting myself with ever more violence and ugliness. Then I gave that up too – I couldn’t do it anymore.

At that time I was living in Le Havre, where I had followed my girlfriend of the time, and I took up painting, which I had resisted until then. Painting relaxed me from my job with the mentally ill. I no longer got high, drank very little, and led a healthy life. I painted mostly on hardboard sheets because canvas still scared me, plus it was expensive. One day I showed my paintings to a woman who organised exhibitions in her literary café, and sometime later I had my first personal exhibition. I even sold paintings. That was cool.

So I took the entrance exam to the art school in Le Havre. Still not really convinced of my artistic talents, I trained as a graphic designer there – at least that’s what it says on my diploma. In reality I detested computers, sticking with drawing by hand, and got into comics, a subject not taught at art college. In 2000 I moved to Belfort in north-east France, where I still live, broke up with my girlfriend, and went back to drinking and smoking like when I was a teenager. And I went back to painting.

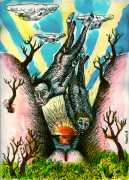

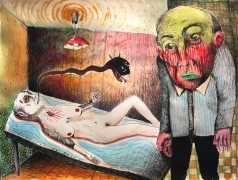

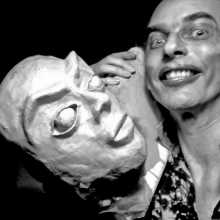

When I was very young I had visions. A ghost came to visit me every evening – I saw his silhouette behind the glass door of my room. It only disappeared when my screams alerted my parents, who turned on the light to see what was going on. I painted this silhouette many times, surrounding my bed with ghost portraits. I was chasing my demons. I finally decided to drop everything, including work and family, in order to devote myself to my art.

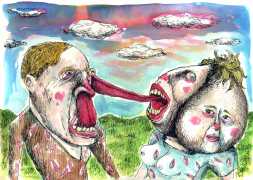

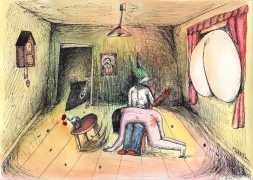

I had maintained my appetite for madness, even though I now knew its taste. It wasn’t beautiful, glamorous or romantic. It was dirty, it stank, it was unvarnished humanity. It was also the people we hide away because they are different, that we lock up because they are dangerous. I was still angry, dominated by the same raw emotions, the same feelings, the same rage. All of this had to come out somehow.

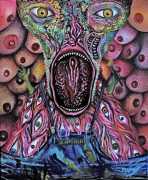

So I scratched out hundreds of drawings, painted hundreds of canvases. And the more I screamed in black and white and in colour, the more I wanted to scream. Was my anger feeding on itself? Without a doubt. Everywhere I looked I saw only lies, deceit, stupidity and hypocrisy. My art is a way of putting people in front of themselves. Look how ridiculous you are, how stereotypical your attitudes. Your whole life looks like a pantomime, a grotesque and absurd farce, and so does mine. So we have two choices – either we accept this and continue on the same bankrupt path, or the stupidity gets to us and we take the opposite course, the path of revolt.

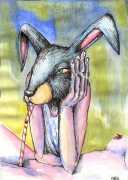

It’s by showing the darkness that we appreciate the light. In my art both are present, to the point of sometimes merging. The shimmering colours are decoys, traps. They are there to attract the viewer, they are beautiful so as to make us abandon mistrust. So we see these sneering monsters, these lips open to nothingness, these rotting sexes. But it’s too late, the damage is done. It’s like those medical books I saw as a child, which impressed me so strongly that even forty years later I don’t really understand why they aroused such fascination and rejection.

In 2010 I was contacted by the French publisher of Le Dernier Cri, Pakito Bolino. He had seen my drawings on the internet and asked if I would send him some of them in order to include them in an anthology entitled Hôpital Brut. Eight years later he contacted me again for the twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Le Dernier Cri. This time it was the paintings from my animal series that interested him. Since then I have since regularly collaborated with him for various exhibitions and works. I had finally found my artistic family, which has extended since then to include Blanquet and the United Dead Artists.

I still self-publish regularly, small graphic works, with or without text. When I’m lucky I exhibit my works. When God looks me straight in the eye and I feel his big hairy hand resting on my weak, rheumatic crippled shoulder, I have even been known to sell something. But I don’t really believe he gives a fuck!

Patrick Jannin’s website is here, and his Instagram page can be found here.

We would like to thank our Russian friend Yuri for suggesting the inclusion of this artist.