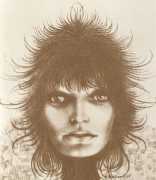

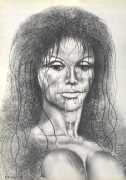

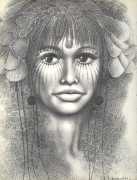

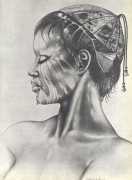

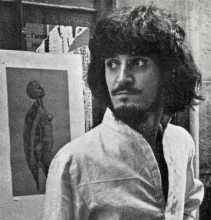

The French erotic artist Raymond Bertrand, not to be confused with the American muralist Raymond Clarence Bertrand (1909–86), is one of those comet-like practitioners who streak briefly across the cultural landscape in response to a particular trend and then disappear from the scene, never to be seen again. At the time when his style was in vogue his work was likened favourably to that of Leonor Fini, but as nobody now seems to know where he came from and where he went after the mid-1970s there is little opportunity to place him and his work within an artistic tradition.

The French erotic artist Raymond Bertrand, not to be confused with the American muralist Raymond Clarence Bertrand (1909–86), is one of those comet-like practitioners who streak briefly across the cultural landscape in response to a particular trend and then disappear from the scene, never to be seen again. At the time when his style was in vogue his work was likened favourably to that of Leonor Fini, but as nobody now seems to know where he came from and where he went after the mid-1970s there is little opportunity to place him and his work within an artistic tradition.

In 2007 the artist and designer John Coulthart wrote about Bertrand in his Feuilleton blog, adding what little information he knew, and which we are pleased to share.

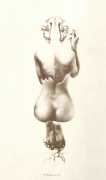

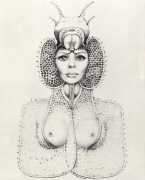

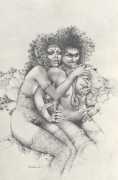

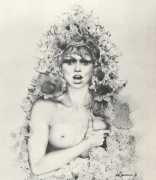

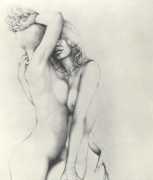

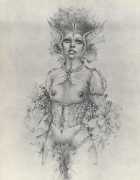

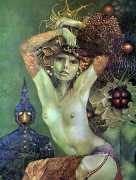

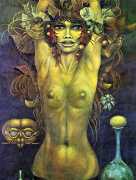

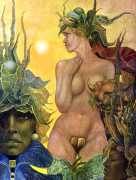

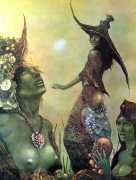

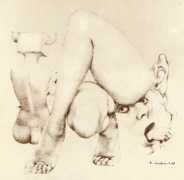

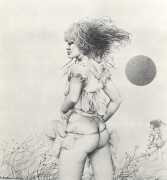

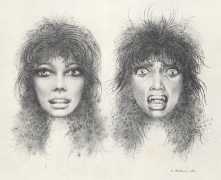

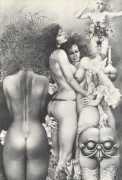

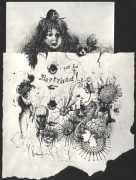

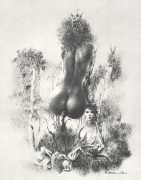

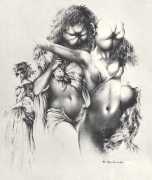

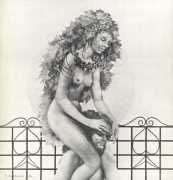

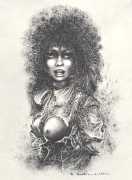

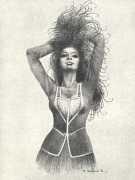

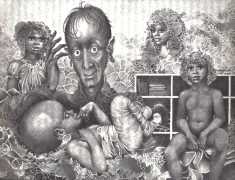

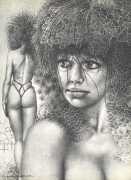

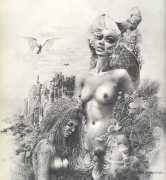

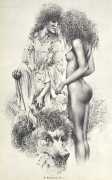

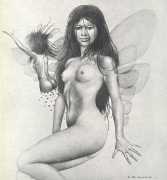

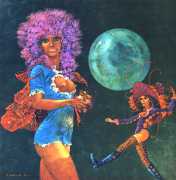

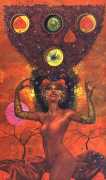

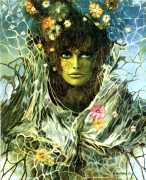

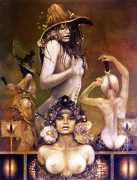

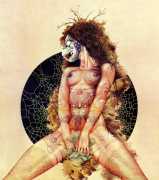

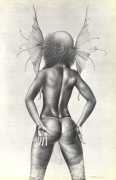

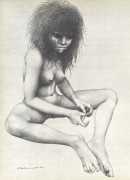

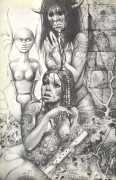

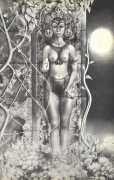

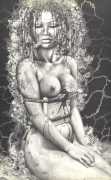

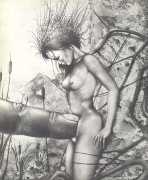

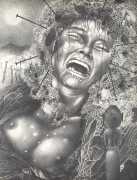

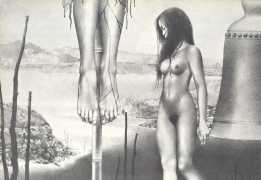

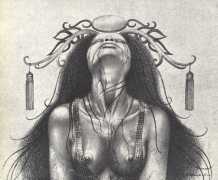

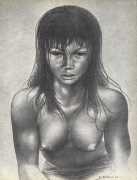

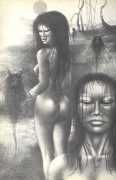

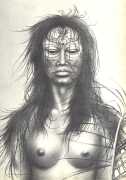

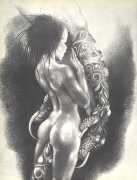

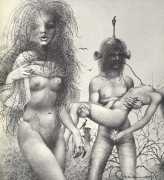

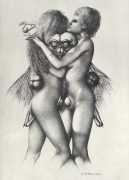

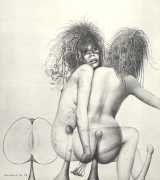

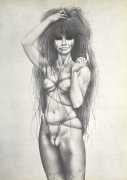

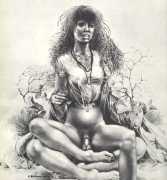

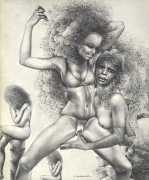

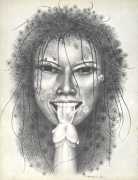

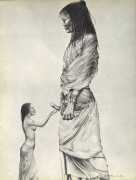

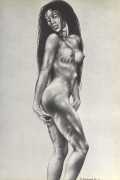

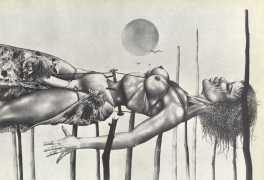

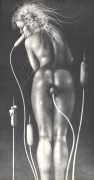

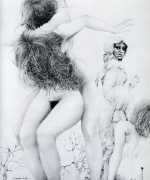

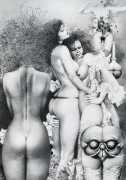

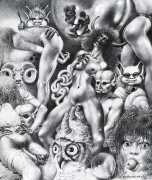

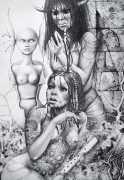

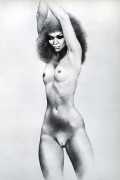

The French publisher Eric Losfeld, well-known for producing erotica, published a couple of large, limited edition collections of Bertrand’s work in 1969 and 1971, which have become increasingly hard to find. If it seems surprising that these haven’t been reprinted, it may be that Bertrand’s concerns are too weird or simply too unpleasant for contemporary tastes. Many of his ink drawings, and some of his paintings, seem to have begun life as decalcomania splotches, a Surrealist technique invented by Oscar Dominguez as a means of injecting chance into the creative process. Decalcomania produces random patterns which the artist then elaborates upon. Max Ernst’s famous ‘Europe After the Rain’, and a number of his other paintings from the 1940s, began life as a field of vaguely organic marks created by pressing thickly applied paint to the canvas with a sheet of glass or paper. Bertrand used ink stains in a similar way, with the result that most of his doe-eyed female figures (and his figures are nearly always women) are fringed by leafy or fungal growths. Many of his scenes are a kind of lesbian equivalent of the human/alien entanglements one finds in William Burroughs’ more elaborate flights of fancy. If his women aren’t being absorbed into some organic mass, they’re often being subject to investigation (even impalement) by spikes or claws, and here we perhaps find the reason his work remains out of print. Feminists then and now would have taken a dim view of Bertrand’s more violent works; even if Taschen did produce a Bertrand collection, it’s unlikely that many of the more grotesque pictures would be included.

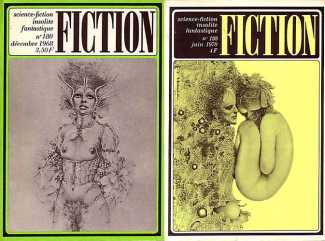

We know that Bertrand contributed regularly to French fantasy and science fiction magazines in the late 60s and early 70s. Fiction was the leading French SF magazine, and sported a fascinating range of cover art especially from the mid-60s onwards. Artists at that time included Philippe Druillet and Philippe Caza, both of whom would become big names in the comics world a few years later. Galaxie was the French edition of American magazine Galaxy, and featured unique material among its translations of Anglophone works. Being French, there’s a greater amount of flesh on display than you’d find on magazine covers in the US and UK; some of this is as salacious as anything else from the period although at least one of the artists drawing naked females was a woman, Sophie Busson. Naked females emerging from – or being absorbed by – strange vegetation, polyps or aquatic organisms were Bertrand’s métier, so that’s mostly what one finds here. Few of the covers seem to relate to the magazine’s contents, and the artists appear to have been free to draw what they liked; in the case of Druillet that means his usual Lovecraftian architecture. An exception is issue 198 of Fiction which has an article about Bertrand’s work by Jacques Chambon, ‘Raymond Bertrand et l’art de l’amour’.

If any of our readers is able to add more information about the enigmatic Raymond Bertrand, we would love to hear from you.