Achille Jacques-Jean-Marie Devéria, whose name is associated with some of the best erotic illustration from the 1840s, was fortunate in being in the right place at the right time – romantic Paris during one of its most libertine periods. He showed an early aptitude for drawing, and became a student of Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson and Louis Lafitte. In 1822 he began exhibiting at the Paris Salon, and around 1825 opened an art school with his brother Eugène, who was also an artist.

Achille Jacques-Jean-Marie Devéria, whose name is associated with some of the best erotic illustration from the 1840s, was fortunate in being in the right place at the right time – romantic Paris during one of its most libertine periods. He showed an early aptitude for drawing, and became a student of Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson and Louis Lafitte. In 1822 he began exhibiting at the Paris Salon, and around 1825 opened an art school with his brother Eugène, who was also an artist.

By 1830 Devéria had become a successful illustrator, and had published many lithographs in the form of book illustrations and albums, such as his 1828 illustrations to Goethe's Faust. His father-in-law, Charles-Etienne Motte (1785–1836), was print seller, which gave Achille ready access to an appreciative market.

Devéria was also well known for his portraits of artists and writers, whom he entertained in his Paris studio on Rue de l’Ouest. His sitters included Alexandre Dumas, Prosper Mérimée, Sir Walter Scott, Jacques-Louis David, Alfred de Musset, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve, Honoré de Balzac, Théodore Géricault, Victor Hugo, Marie Dorval, Alphonse de Lamartine, Alfred de Vigny, Jane Stirling and Franz Liszt.

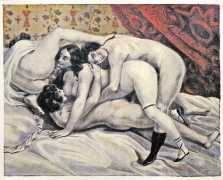

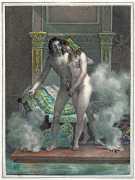

Achille Devéria was enormously prolific, producing well over three thousand works over the course of his career. In association with his father-in-law he targeted several markets, in such a way that explicitly sexual prints did not conflict with his scenes of contemporary society. Though art historians praised Devéria’s skills and curators went on to exhibit his work, they took care to avoid his eroticism, yet his eroticism was everywhere and offers a great deal of insight into the artist.

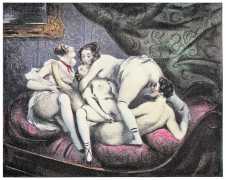

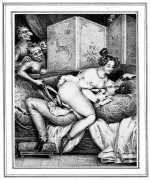

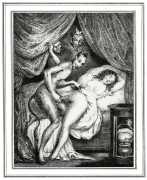

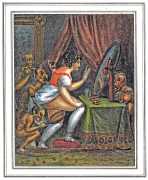

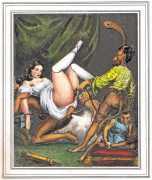

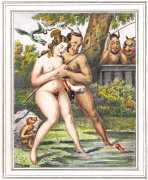

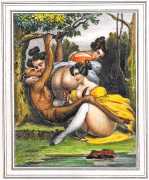

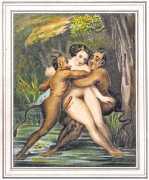

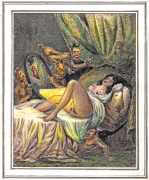

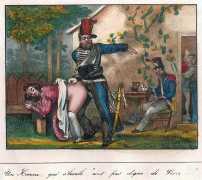

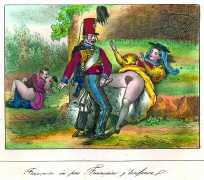

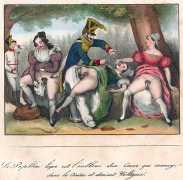

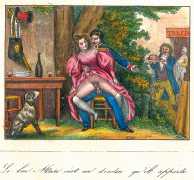

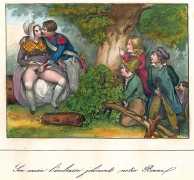

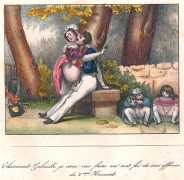

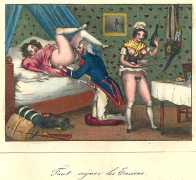

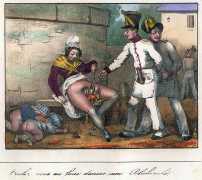

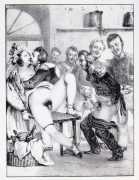

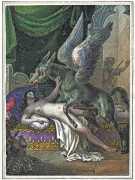

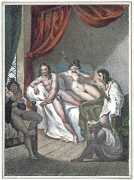

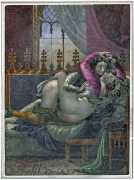

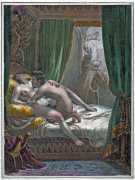

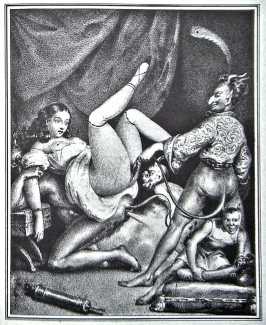

In 1830 he contributed to a compendium of erotica titled Imagerie galante, and in 1833 he illustrated Gamiani, the classic erotic tale of lesbianism. He managed to generate controversy with one odalisque, a painting of a loosely clothed woman reclined on a divan smoking a cigarette. He also illustrated a satanic-erotic piece of explicit literature called Diabolico foutro-manie (1835), where devils penetrate young maidens with their tails. In 1838 he illustrated Le livre des mille nuits et une nuit (The Thousand and One Nights), a collection of historical and erotic tales. He depicted orgies of every conceivable configuration: soldiers in a field, aristocrats in their homes, women cuckolding their husbands in plain view. In one print, a man uses a candlestick on himself while he enters a woman from behind.

It is interesting that while explicit imagery was technically illegal in France at the time it was not actively policed. The art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau notes that while Devéria’s erotic prints were illegal, the majority of prosecutions during this period were against prints that criticised the government. Pornographic imagery seems to thrive during periods of radical transition, some of it playing a dual role of erotic edification and scathing social or political commentary. While some of Devéria’s explicit imagery was political, he avoided critiquing the current government. Many believe that his explicit visual language paved the way for artists like Courbet and Manet, who would bring the candour of lithography to the respected medium of painting, and eventually shatter the traditional politeness of art.

In 1849 Devéria was appointed director of the Bibliothèque Nationale’s department of engravings and assistant curator of the Louvre’s Egyptian department, and he spent his later years travelling in Egypt, making drawings and transcribing texts.