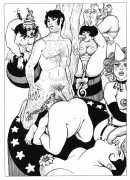

Georges Pichard was in many ways the godfather of the French cartoon industry. He worked with Goscinny and Uderzo on Pilote, the weekly magazine which launched Astérix, and taught several illustrators such as Marcel Gottlieb, better known as Gotlib, who created the Droopy-like dog Gai Luron and Superdupont, both great favourites in France. To generations of French teenagers who grew up in the sixties and seventies, however, Pichard is best remembered as an accomplished draughtsman specialising in racy strip cartoons depicting the adventures of his scantily clad heroines Blanche Epiphanie and Paulette. Published in the satirical magazine Charlie Mensuel, Paulette in particular attracted the attention and condemnation of the right-wing politicians Jean Royer and Michel Debré.

Georges Pichard was in many ways the godfather of the French cartoon industry. He worked with Goscinny and Uderzo on Pilote, the weekly magazine which launched Astérix, and taught several illustrators such as Marcel Gottlieb, better known as Gotlib, who created the Droopy-like dog Gai Luron and Superdupont, both great favourites in France. To generations of French teenagers who grew up in the sixties and seventies, however, Pichard is best remembered as an accomplished draughtsman specialising in racy strip cartoons depicting the adventures of his scantily clad heroines Blanche Epiphanie and Paulette. Published in the satirical magazine Charlie Mensuel, Paulette in particular attracted the attention and condemnation of the right-wing politicians Jean Royer and Michel Debré.

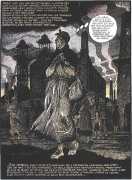

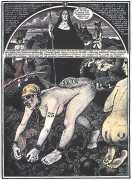

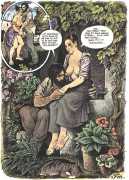

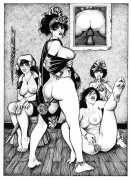

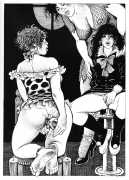

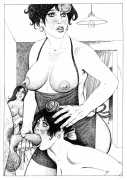

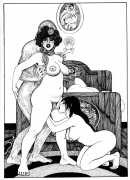

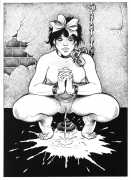

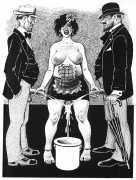

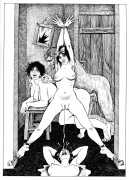

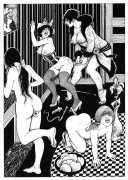

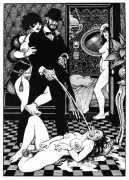

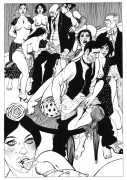

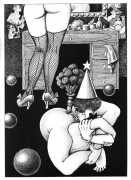

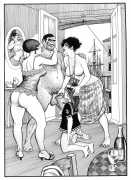

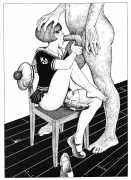

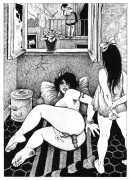

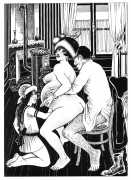

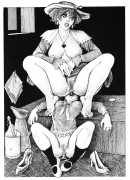

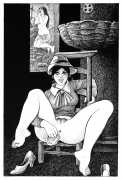

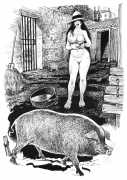

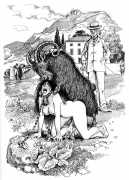

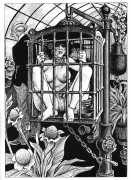

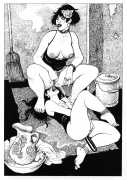

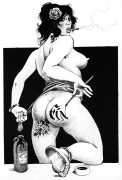

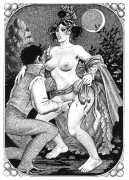

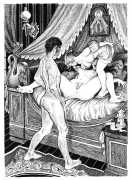

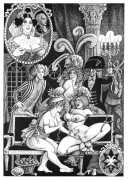

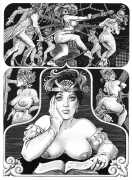

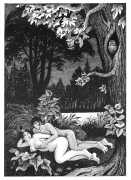

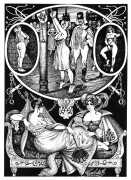

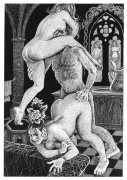

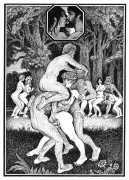

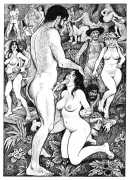

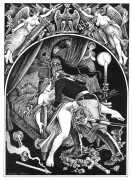

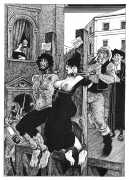

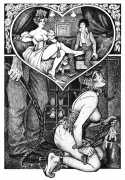

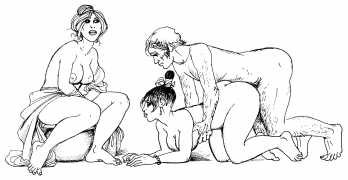

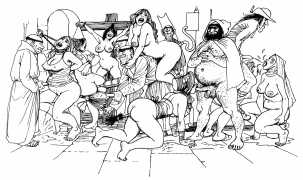

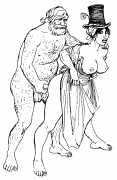

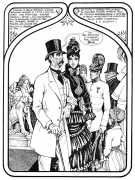

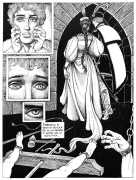

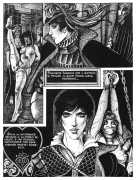

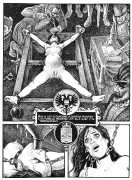

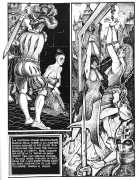

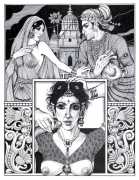

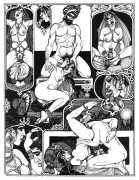

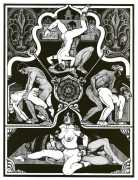

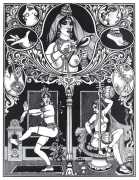

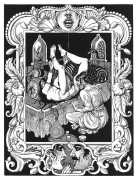

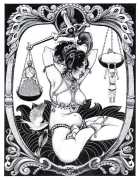

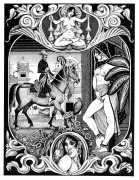

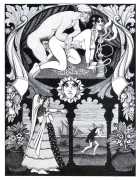

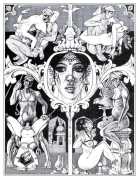

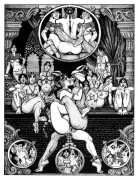

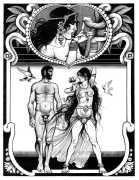

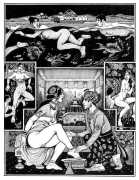

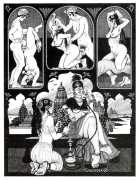

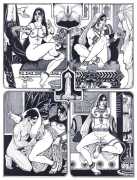

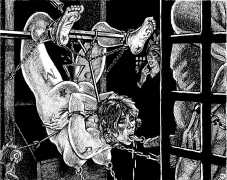

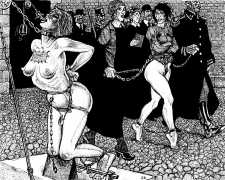

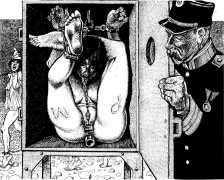

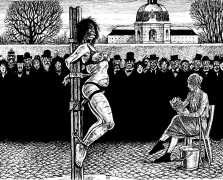

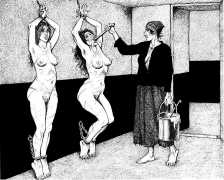

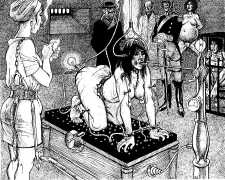

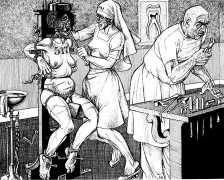

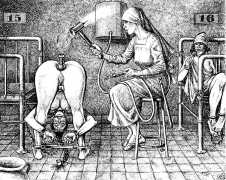

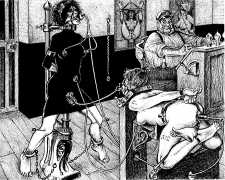

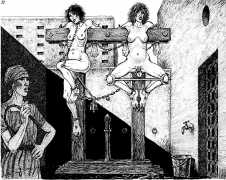

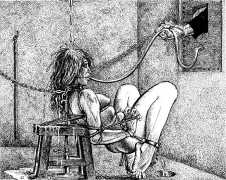

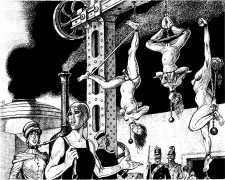

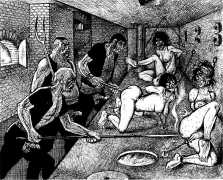

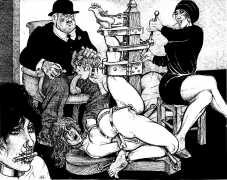

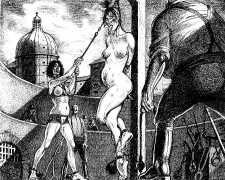

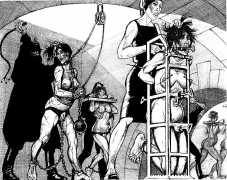

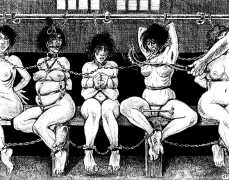

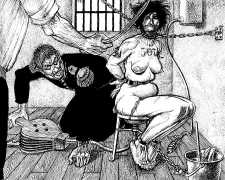

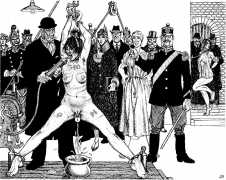

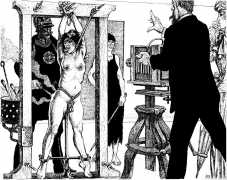

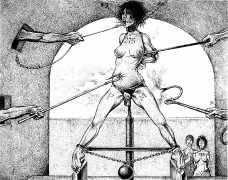

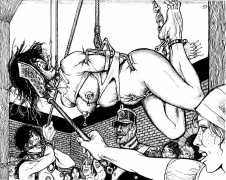

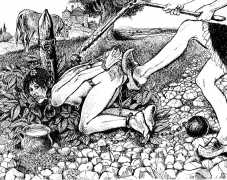

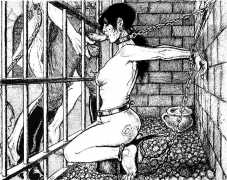

A cross between the US underground illustrators Robert Crumb and Eric Stanton, and clearly inspired by Aubrey Beardsley, Pichard worked exclusively with pen and ink to develop an ornate style which suited the out-of-the-frying-pan-into-the-fire situations his female characters found themselves in.

Pichard grew up in Paris and studied at the Ecole des Arts Appliqués, an institution he would later rejoin as lecturer. After the Second World War, he worked in advertising and publishing as an illustrator and caricaturist before drawing his first strip cartoon, Miss Mimi, in 1956 for the magazine La Semaine de Suzette.

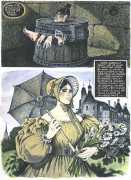

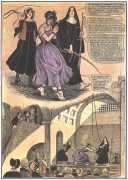

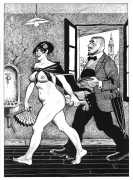

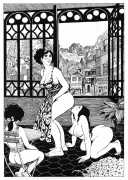

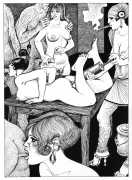

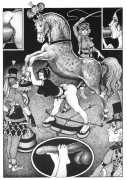

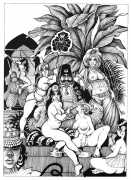

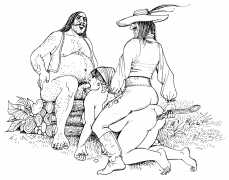

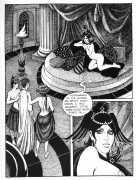

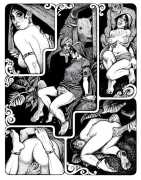

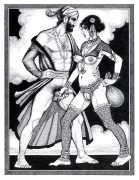

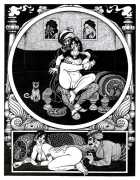

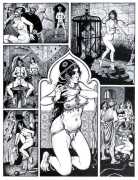

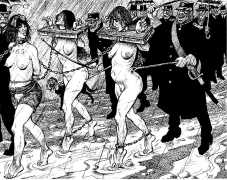

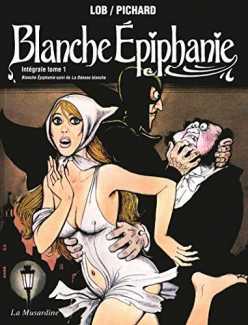

In 1964 he teamed up with the scriptwriter Jacques Lob to create Ténébrax for the magazine Chouchou, and Submerman for the weekly Pilote, But the pair really caught the mood of the swinging sixties with Blanche Epiphanie, an innocent young woman who constantly finds herself in compromising situations. First published in the daily France-Soir in 1967, the cartoon shocked and delighted Parisians in equal measure. As the events of May 1968 shook France to its foundations, Blanche Epiphanie experimented with sex and drugs and travelled the world from the bordellos of New York to the harems of North Africa. She even made a Jane Fonda-style trip to Vietnam.

In 1964 he teamed up with the scriptwriter Jacques Lob to create Ténébrax for the magazine Chouchou, and Submerman for the weekly Pilote, But the pair really caught the mood of the swinging sixties with Blanche Epiphanie, an innocent young woman who constantly finds herself in compromising situations. First published in the daily France-Soir in 1967, the cartoon shocked and delighted Parisians in equal measure. As the events of May 1968 shook France to its foundations, Blanche Epiphanie experimented with sex and drugs and travelled the world from the bordellos of New York to the harems of North Africa. She even made a Jane Fonda-style trip to Vietnam.

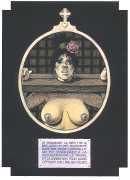

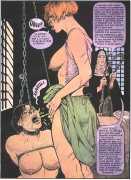

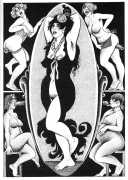

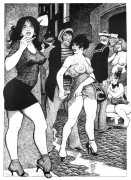

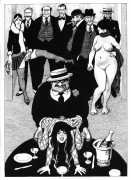

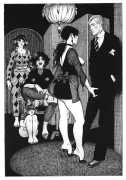

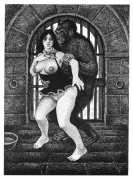

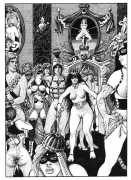

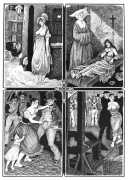

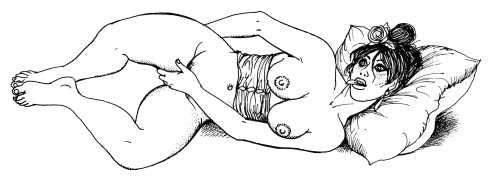

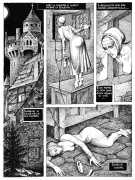

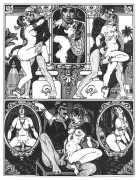

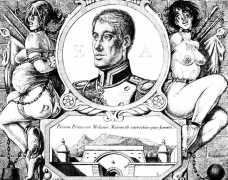

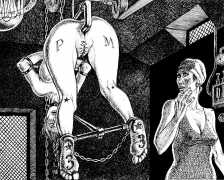

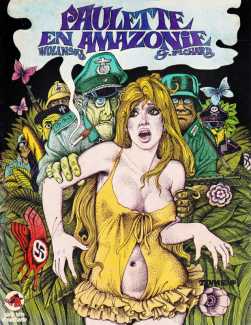

Pichard created other busty heroines with exotic names like Sahara, Athéna, Lolly Strip and Circé, but it was his Brigitte Bardot lookalike Paulette who really set the cat among the pigeons in 1970. Pichard created a subversive and liberated character who went on demonstrations and confronted the status quo. Paulette’s obvious charms, often displayed on the cover of Charlie Mensuel, meant that the publication was banned from newsagents in more conservative parts of France, which only added to her popularity.

Pichard created other busty heroines with exotic names like Sahara, Athéna, Lolly Strip and Circé, but it was his Brigitte Bardot lookalike Paulette who really set the cat among the pigeons in 1970. Pichard created a subversive and liberated character who went on demonstrations and confronted the status quo. Paulette’s obvious charms, often displayed on the cover of Charlie Mensuel, meant that the publication was banned from newsagents in more conservative parts of France, which only added to her popularity.

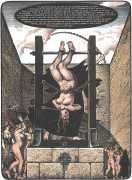

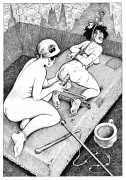

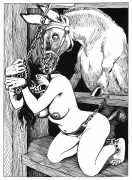

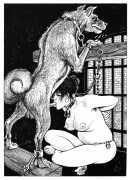

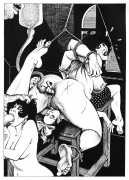

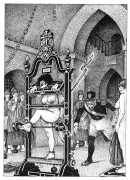

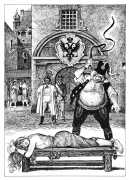

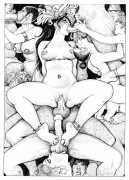

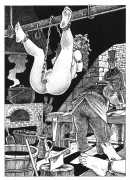

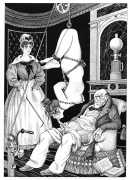

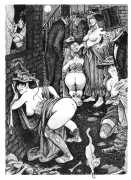

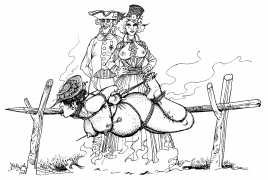

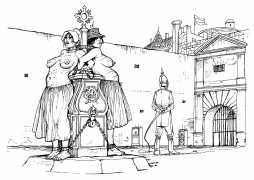

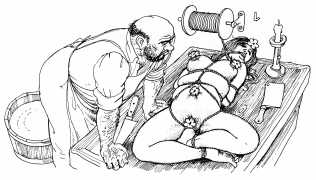

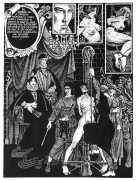

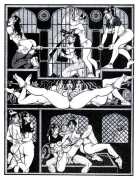

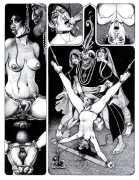

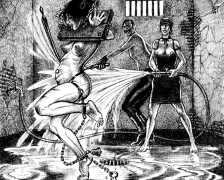

In 1977 Pichard made the move into explicit sado-masochism with the publication of Marie-Gabrielle de Saint-Eutrope, set in the eighteenth century and a powerfully illustrated accusation against the crimes committed in the name of religion. Sexual violence against women continued to be his main theme until his last book, Maison de correction. He always maintained that he was an avowed supporter of feminism and the power of women; whether he consciously chose to illustrate transgressive violence in order to draw attention to its prevalence, especially in historical settings, is a question that must be left to his critics.