‘I am not a woman painter,’ Leonor Fini told her biographer Peter Webb. ‘I am a painter, and I am independent.’ A very good painter she was, in almost every artistic medium that exists, but she was also much more – a strong, highly-intelligent, thoughtful, appropriately-opinionated whirlwind of originality and creativity, whose personal life mirrored her art at every turn.

The short version of her biography is that she was born in Buenos Aires and raised in Trieste (then part of Italy) by her mother, her Argentinian father having absented himself. Self-taught in art but having been drawing since a young girl, she moved to Milan at seventeen to study art, and ended up in Paris in 1931, which would be her base for the rest of her life.

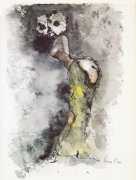

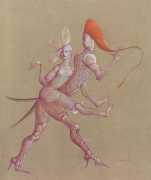

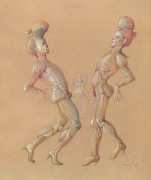

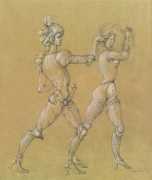

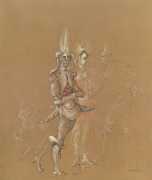

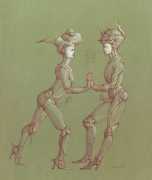

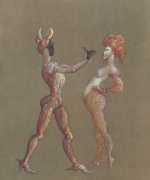

Leonor Fini is best known as a painter exploring the rich borderlands of realism and surrealism, but her long artistic career also included successful forays into set and costume design for theatre, ballet, opera and film, and even product design – she created the renowned torso-shaped perfume bottle for Schiaparelli’s perfume Shocking.

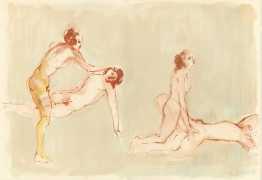

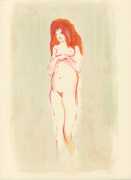

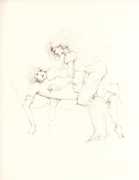

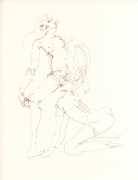

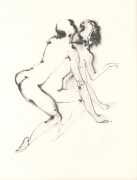

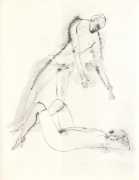

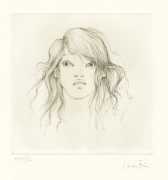

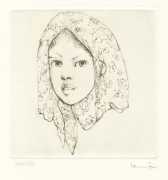

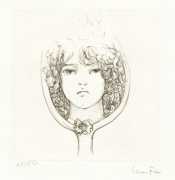

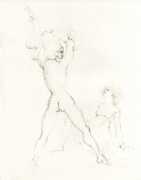

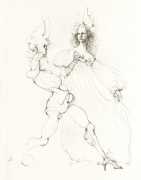

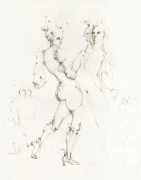

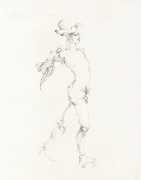

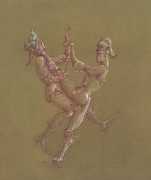

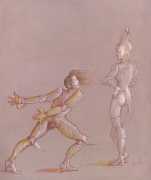

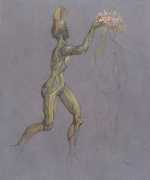

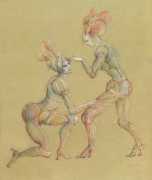

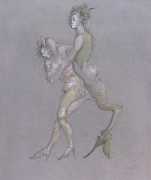

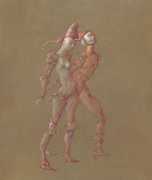

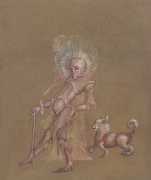

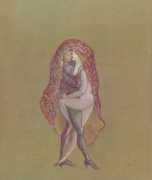

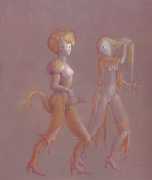

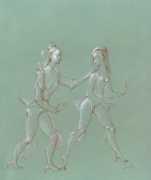

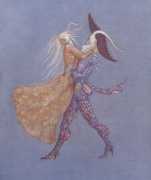

And she was a prolific and highly creative illustrator, inspired by a wide range of texts, nearly all chosen by her, which in one way or another spoke to her at a profoundly emotional and intellectual level. It is her book and portfolio illustrations we concentrate on here, starting with her 1945 illustrations for the Marquis de Sade’s Juliette, with its telling subtitle ‘les prospérités du vice’ – ‘vice amply rewarded’.

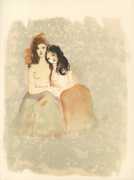

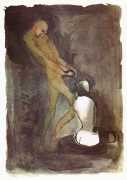

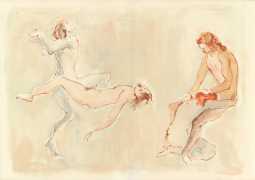

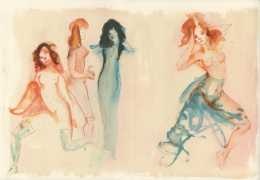

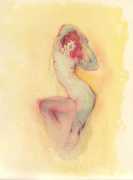

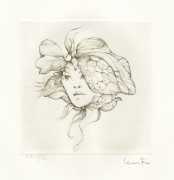

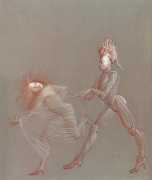

A predominant theme of Leonor Fini’s art is the complex relationship between the sexes, primarily the interplay between the dominant female and the passive, androgynous male. In many of her most powerful paintings, the female takes the form of a sphinx, often with the face of the artist. Complex intimate relationships were also a feature of her personal life. As she wrote of herself, ‘Marriage never appealed to me, and I’ve never lived with just one person. Since I was eighteen I’ve always preferred to live in a sort of community, a big house with my atelier and cats and friends, one a man who was rather a lover and another who was rather a friend. And it has always worked.’ In fact she was married, for a few months in 1938, to Fedrico Veneziani, but he was soon replaced by more permanent intimates, by far the two most important being Italian count Stanislao Lepri, who abandoned his diplomatic career shortly after meeting Fini, and the Polish writer Konstanty Jeleński, known as Kot, who Leonor was delighted to discover was the illegitimate half-brother of Sforzino Sforza, one of her favourite lovers. Kot joined Fini and Lepri in their Paris apartment in October 1952 and the three remained inseparable until their deaths. And then there were the cats, mostly Persian and at their height twenty-three in number; they often shared her bed and her dining table.

Leonor had clear and strongly-held ideas, in many ways far ahead of her time, about how women and men could coexist equally and supportively. ‘It is obvious that women have been mistreated by men for so long,’ she wrote. ‘They have always had to submit to men. It is no wonder that they are going on the offensive now. But I am not a feminist, and hate being claimed as a feminist. I like men who are intelligent, sensitive, have real understanding, men who are aware of their feminine side. I especially like homosexual men and androgynous men. I like to think of myself as androgynous.’ It is this androgyny which has confused many of Leonor Fini’s admirers, who have confused it with bisexuality. There is no doubt that Leonor loved women deeply – she was close to many of her female artistic contemporaries – but she was also passionately attracted to the right sort of men.

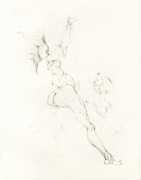

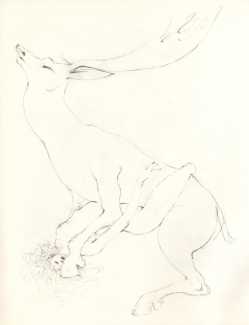

The affair she had in 1966 with married Paris businessman Paul Henri was as intense as they get, as her love letters and drawings testify – ‘Dear stag, dear violent body, dear brightness, dear beauty, when you make love you are ageless, you become like the forces of nature, the wind, the waves.’ It didn’t last very long, but it was the freedom of the fully-lived experience that was most important to Leonor.

Leonor Fini is fortunate to have in art critic and academic Peter Webb the perfect biographer, and his 2009 survey of her life and work, Sphinx: The Life and Art of Leonor Fini, is both comprehensive and inspiring.