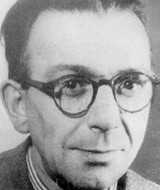

The Austrian painter, graphic designer and book illustrator Otto Rudolf Schatz is often regarded as one of the most significant artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement of the 1920s and 30s, though such a characterisation easily oversimplifies both the movement and Schatz’s relationship with it. ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ is usually translated as ‘New Objectivity’, but as the art historian Dennis Crockett points out, there is no direct English translation – ‘Sache’ means a thing, fact, or object, and ‘sachlich’ factual, matter-of-fact, practical, precise. Thus a closer translation of Neue Sachlichkeit might be ‘a new matter-of-factness’, and that certainly describes Schatz and his work.

The Austrian painter, graphic designer and book illustrator Otto Rudolf Schatz is often regarded as one of the most significant artists of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement of the 1920s and 30s, though such a characterisation easily oversimplifies both the movement and Schatz’s relationship with it. ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ is usually translated as ‘New Objectivity’, but as the art historian Dennis Crockett points out, there is no direct English translation – ‘Sache’ means a thing, fact, or object, and ‘sachlich’ factual, matter-of-fact, practical, precise. Thus a closer translation of Neue Sachlichkeit might be ‘a new matter-of-factness’, and that certainly describes Schatz and his work.

Schatz was born into a middle-class civil servant’s family, and after leaving school received excellent training at the Vienna School of Applied Arts. His eight months of military service left him disillusioned, and he remained a committed pacifist all his life. In 1919 he tried his hand at a number of different jobs, before feeling ready in 1920 to embark on a career as an independent artist. He was an excellent draftsman and quickly mastered a wide range of graphic techniques, including watercolour, tempera, oil painting, woodcut and lithography, adeptly employing each medium according to his chosen subject.

He had a gruff and explosive temperament, but also revealed a sensitive side, for example in his children’s books and drawings for adolescents, and his assistance with the calligraphy studies of the thirteen-year-old son of the gallery owner Otto Kallir-Nirenstein. He was driven incessantly by his art and was happiest when working. From 1928 to 1938 he was a member of the Hagenbund (a group of Austrian artists formed in 1899, named after the proprietor of the Vienna hostelry the group frequented), and like many of his colleagues had a large network of fellow artists both nationally and internationally.

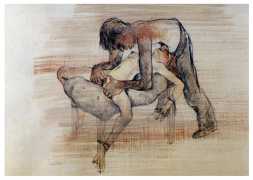

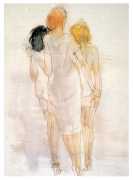

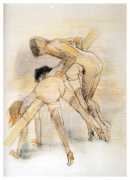

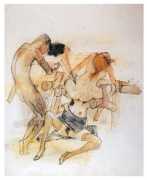

Schatz was well informed about contemporary artistic developments, but having initially been an admirer of Egon Schiele he showed little interest in stylistic movements or luminaries of the art world, instead choosing to work in whichever manner best expressed his personal outlook on life, sometimes in different styles simultaneously. He was also quite clear about the distinction between works he made to earn money and those he created for the sake of art. To make a living and put food on the table he painted tavern scenes and landscapes. Whenever he was in severe financial straits, he also created erotic pictures in substantial numbers, which were guaranteed to sell. This does not mean that his erotic work was always produced hurriedly; he was something of a perfectionist, and depending on his mood and the respective client his erotic output ranged from the edge of the pornographic to depictions of a powerful, unbounded eroticism.

In 1934 Schatz met Valerie ‘Vally’ Wittal, the daughter of a wealthy Jewish shop-owner from Brno in Moravia, now part of the Czech Republic, and after a short and passionate romance they were married in December of that year. For Otto the new-found affluence provided the resources to travel and become more involved in the international art scene, and from 1935 to 1937 the couple travelled extensively throughout Europe and to the USA. His large canvases of Venice, southern France and New York attracted much attention, and today fetch a high price. Because of Schatz’s outspoken anti-fascist sentiments and his wife’s Jewish origins, the couple fled Vienna when German troops entered Austria in March 1938, going first to Brno and then to Italy. When Nazi racial laws also came into effect in Italy, they returned to Brno and eventually settled in Prague. In October 1944 Schatz was betrayed to the Gestapo, interned for sixteen days, and in November 1944 deported to a labour camp in Klettendorf near Breslau. Vally, meanwhile, was interned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

After the Russians liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau, Schatz was moved via Gräditz concentration camp to Bistritz bei Beneschau, where he remained until the end of the war in early May 1945, having been critically ill for the final six weeks of his internment. Back in Prague he was reunited with Vally, who had also survived her internment. The marriage was not to last, however; Vally was well aware of her husband’s erratic lifestyle and his relationships with several other women, and filed for divorce, shortly afterwards emigrating to the USA. Schatz returned to Vienna in November 1945, taking what was left of his possessions and pictures. In the years that followed, he found champions in City Councillor Viktor Matejka and later in vice-mayor Hans Mandl, and his old friend Erich Leischner, now a member of the Vienna senate, who provided him with commissions for the City of Vienna. A lifelong smoker, he died of lung cancer in April 1961.

In the postscript to the 2018 Dorotheum monograph on Schatz’s life and work, Stella Rollig sums up his achievement like this:

‘Considering Schatz’s artistic achievements in relation to his recognition by the wider art world, it becomes clear that, unlike other Austrian artists of the time, it was his steadfast political commitment that provided the inspiration for his work, but which also, in combination with the course of history, contributed to the fact that he and his work almost sank into oblivion after his death. This was due in the first instance to the fault lines in his biography: his political persecution and exile, and the resulting discontinuities in his development. Furthermore, he was uninterested in questions of style, which was no doubt detrimental to the reception of his art.

His intention, however, was never to create art for the purposes of intellectual discourse, but to draw on his experiences to produce works that encapsulated the spirit of the times. Today in particular, his multifaceted artistic statements are fascinating in their candour and immediacy. He exemplifies the ability of the avant-garde to respond creatively to life and to transpose it into art.’

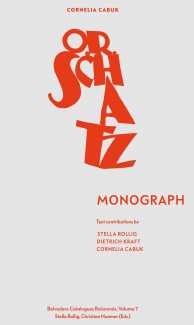

The Vienna Dorotheum Museum’s Belvedere Research Centre’s comprehensive 2018 monograph of Otto Rudolf Schatz can be found here. Much of the information in this profile of Schatz is drawn from this source.

The Vienna Dorotheum Museum’s Belvedere Research Centre’s comprehensive 2018 monograph of Otto Rudolf Schatz can be found here. Much of the information in this profile of Schatz is drawn from this source.