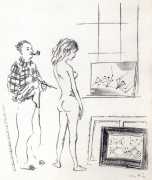

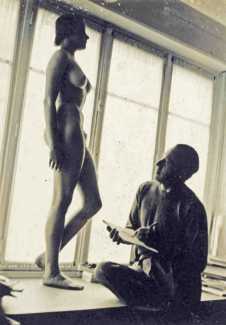

It is remarkable that nobody has yet attempted a biography of the fascinating artist, illustrator and designer Marcel Vertès, possibly because, as Nicholas Shakespeare notes in his researches about Priscilla Mais, probably one of Vertès’ lovers, ‘he was a loner who belonged to no movement, fragile, moody, stubborn, impatient’. But this does not begin to describe a complex man who drew constantly and honestly what he saw and imagined, whose creativity extended from etching and painting to film and fashion, and who managed, apparently reasonably successfully, to remain happily married while involved deeply with several other women and spending much of his time in ‘houses of ill repute’. He also had a wicked sense of humour.

It is remarkable that nobody has yet attempted a biography of the fascinating artist, illustrator and designer Marcel Vertès, possibly because, as Nicholas Shakespeare notes in his researches about Priscilla Mais, probably one of Vertès’ lovers, ‘he was a loner who belonged to no movement, fragile, moody, stubborn, impatient’. But this does not begin to describe a complex man who drew constantly and honestly what he saw and imagined, whose creativity extended from etching and painting to film and fashion, and who managed, apparently reasonably successfully, to remain happily married while involved deeply with several other women and spending much of his time in ‘houses of ill repute’. He also had a wicked sense of humour.

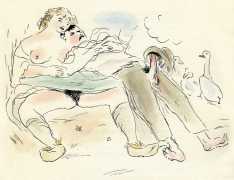

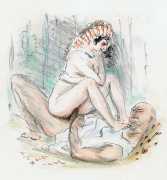

It maybe helps to start with his early sexual experiences, recounted in his 1952 autobiography, Amandes vertes (Green Almonds):

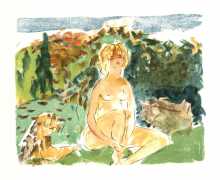

Let’s start with the women, specifically the two women who so impressed the little apprentice male I was then. Number one was Terike, the servant of whom I have already spoken, with her twenty petticoats, stopping at the knees to reveal the white stockings with wide stripes.

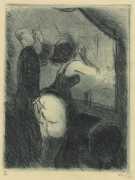

My interest in the little servant was great; I followed her wherever she went. Very hard-working, she made up the rooms, helped the cook, and gave food to the dogs and cats. When she really had nothing to do, she went up to her room. Always behind her, I went there too. Whitewashed, Terike’s room was very pretty. Everywhere on the four walls, and up to the ceiling, pleated well-ironed petticoats were hung in order. They hung in many colours, some simple, others flamboyant, specially reserved for Sundays and festivals.

When she leaned over her ironing board her hips flared out into an enormous sphere, the proportions of which were all the more incredible as I contemplated them from below. A well-formed bust sprang out of this ample ball of tissue.

I do not know what it was that made me ask her to show me what was under the many petticoats. I was convinced that it was her very body that was expanding at this point, yet there were moments when I doubted it, and this problem often worried me, especially in bed before I fell asleep.

When I finally summoned the courage to ask my question, she put the iron down on the board and looked at me in a funny way. Then she began to laugh, and suddenly, grabbing her petticoats with both hands, she raised them up high, flapped them onto her back, and exclaimed, ‘Well, here it is, it’s not complicated!’

When I finally summoned the courage to ask my question, she put the iron down on the board and looked at me in a funny way. Then she began to laugh, and suddenly, grabbing her petticoats with both hands, she raised them up high, flapped them onto her back, and exclaimed, ‘Well, here it is, it’s not complicated!’

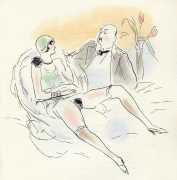

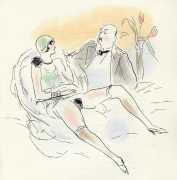

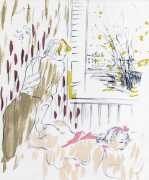

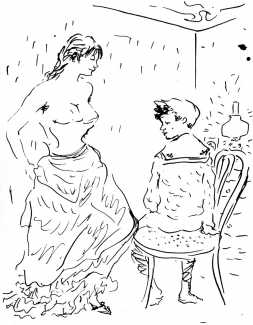

Memory number two is of a neighbour whose husband spent his time on the road, selling various articles to the peasants and rarely returning to his wife. She was beautiful; I could not understand how he could stay away from such a beautiful woman. She always smelled good. She read a lot of German humorous newspapers, and I had permission to go and visit her. We looked together at the large colour pictures of superb women with generous décolletés, the separation of their breasts approaching the sublime.

The beautiful neighbour translated the captions – they made her laugh, but I almost never understood quite why. ‘You like these pictures?’ she asked in a tone of intimacy.

The beautiful neighbour translated the captions – they made her laugh, but I almost never understood quite why. ‘You like these pictures?’ she asked in a tone of intimacy.

I replied in the affirmative, putting my finger on those ornaments I dared not call by their names, calling them ‘big rosy things’. Without saying anything she quickly took off her bodice.

‘Look!’

Her breasts were as beautiful as any in the magazines. I opened my mouth, but could not articulate the slightest sound. Totally mute, I approached. When I was very close to her, the neighbour without a bodice took me by my little shoulders and pushed me towards the door with a firm gentleness.

‘We have to go, it’s getting late.’

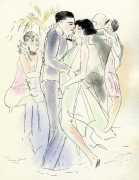

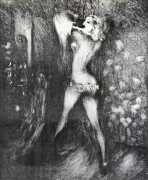

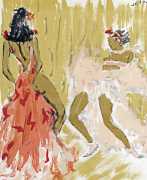

So began a lifetime of fascination with the human body and its interactions with other human bodies. Marcel Vertès was in most of the right places at the right times to make the most of his precocious artistic talent. Born and raised in Budapest, he was in Paris during the vibrant interwar years and then in New York when so many artists fled Europe during the second world war, though he regularly returned to France after the war. While his main work was in illustration and fashion design, one of his claims to fame was as a design consultant to the 1952 award-winning film Moulin Rouge, about Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s 1890s Paris. In the film Marcel’s hand is seen producing ‘original’ Toulouse-Lautrec paintings, the ‘hand of the artist’ being individually credited. Ironically this started a myth that he continued to pass off his own ‘Toulouse-Lautrecs’ as genuine; while it may have been in character for Marcel to prove how stupid art collectors can be, there is no proof that it ever happened.

Of his private life very little has been committed to paper, but he clearly knew the Paris underworld well, and not just as an observer. He regularly frequented several brothels, especially his favourite One-Two-Two, and for nearly thirty years, from 1933 to 1961, conducted a more or less passionate relationship with Gillian Hammond, an Englishwoman living in Paris; he almost certainly also seduced her best friend Priscilla Mais. And all the time he remained married to the ever-present and ever-patient Dora, whose thoughts we may never know but who in the end outlived Marcel by five years and died at the age of 99. In Amandes vertes Marcel wrote tellingly, ‘Dora saw everything, but never said anything that could hurt me’.