A prophet is without honour in their own country, so they say, and with this in mind it is notable that the only illustrated article ever to appear about the prolific and talented French artist Suzanne Meunier was in the London-published Strand Magazine, who gave an interview with her pride of place in their Christmas 1923 issue. It calls her a ‘famous painter’, and indeed her colour postcards and magazine illustrations were well known throughout the 1920s, but a hundred years later she is almost forgotten – in Marcus Osterwalder’s comprehensive Dictionnaire des illustrateurs 1905–1965 she receives just one sentence in the addendum. It goes without saying that it doesn’t help posterity that she was a woman, who was mainly ‘only’ an illustrator of ephemera rather than a ‘real artist’.

A prophet is without honour in their own country, so they say, and with this in mind it is notable that the only illustrated article ever to appear about the prolific and talented French artist Suzanne Meunier was in the London-published Strand Magazine, who gave an interview with her pride of place in their Christmas 1923 issue. It calls her a ‘famous painter’, and indeed her colour postcards and magazine illustrations were well known throughout the 1920s, but a hundred years later she is almost forgotten – in Marcus Osterwalder’s comprehensive Dictionnaire des illustrateurs 1905–1965 she receives just one sentence in the addendum. It goes without saying that it doesn’t help posterity that she was a woman, who was mainly ‘only’ an illustrator of ephemera rather than a ‘real artist’.

Suzanne Marie Alia Meunier-Pouthot (usually called Zette by her family and friends) grew up in Suresnes, an affluent suburb of western Paris. Both her parents, factory owner Albert Meunier-Pouthot and Berthe Point, came from successful business families, and were happy to see their younger daughter follow her talents and attend the Académie Julian. Suzanne Meunier-Point joined the Union of Women Painters and Sculptors, which exhibited her in 1909, but then she felt the urge to expand her horizons, and in 1911 enrolled in the School of Fine Arts in Barcelona, publishing her first drawings in the Catalan review Hojas Selectas.

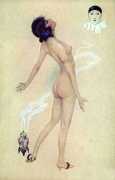

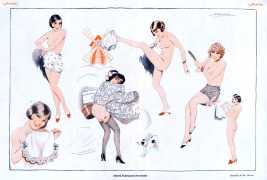

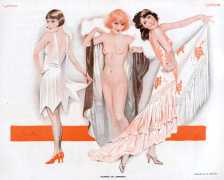

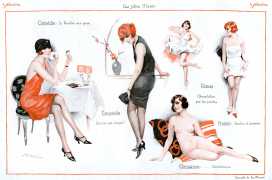

Her first signed illustrations appeared in 1914 in the weekly magazine Pages Folles, then in 1917 she was commissioned by Le Sourire to produce regular two-colour illustrations, a technique she perfected over the next two decades; she was still producing regular illustrations for Le Sourire until 1937. From 1922 she produced illustrations for Eros, ‘a monthly review of physical art’, and her drawings also appeared in La Vie Parisienne, Fantasio and Les Dimanches de la Femme among others.

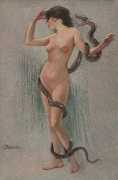

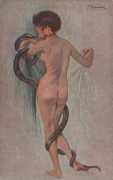

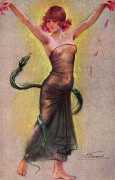

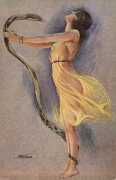

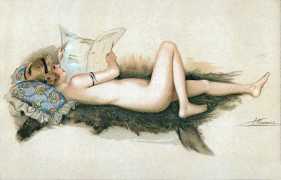

The owners of Le Sourire owned a sister company, La Librairie de L’estampe, specialising in picture postcards. Alongside a distinguished roll-call of artists including Richard Kirchner, Marcel Feliu, Chéri Hérouard, Léo Fontan and Gerda Wegener, Suzanne was commissioned to produce paintings that could be reproduced as postcards. At first they were printed single colour, but from around 1915 La Librairie de L’estampe started to produce high-quality full-colour postcards in sets of six or seven, and by this time Suzanne was one of their best-selling artists. Their 1916 catalogue includes the following Meunier sets of ‘galante’ cards:

Series 26 En costume d’Eve (In Eve’s clothing)

Series 33 Les secrets de la Parisienne (Secrets of the Parisienne)

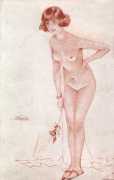

Series 43 Études de nu (Nude studies) (sanguines)

Series 53 Le nu moderne (The modern nude)

Series 56 Histoire d’un flirt (Story of a flirtation)

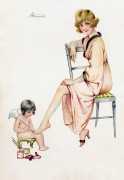

Series 60 Ohé! Cupidon (Hey! Cupid)

Series 64 La femme et le serpent (The woman and the snake)

Series 66 Trottins de Paris (Models of Paris)

Series 74 Les Parisiennes à la mer (Parisiennes at the seaside)

Series 77 Le lever de la Parisienne (The rise of the Parisienne)

Series 79 Nos Montmartroises (Our Montmartre women)

Series 86 Les danses à la mode (Fashionable dances)

Series 98 Les sept péchés capitaux (The seven deadly sins)

In addition there were another six sets of ‘non-galante’ subjects, so at that time there were well over a hundred Meunier colour designs in circulation, not to mention a similar number of earlier single-colour cards. By the time sales of illustrated postcards started to decline in the late 1920s, Suzanne had probably contributed more than three hundred paintings to La Librairie de L’estampe.

Suzanne Meunier’s work was known beyond France. In 1935 she was commissioned by Sydney Z. Lucas, the New York owner of the Camilla Lucas Gallery and organiser of the Paris Etching Society, who showed her work and licensed some of it to American postcard manufacturers.

And all the while she did not stop painting. In 1916 she exhibited at the Joubert Gallery in Paris, and in following years in Richebourg, Nancy and Bourdeaux. She produced a number of cover illustrations for the publisher Albin Michel, and illustrations for advertisements in France and America.

Suzanne’s personal life appears to have been uniformly settled and content, her left-wing bourgeois family values matched with a comfortable marriage in 1920 to bank manager Antony ‘Any’ Gérard. With a well-appointed studio in Paris’s upmarket boulevard Montparnasse, regular work and income, and annual holidays in Chamonix, she continued to work and exhibit throughout the 1930s. After the war the couple moved gently into retirement; Any died in 1966 and Suzanne stopped painting. As her biographer Daniel Auliac tells us, ‘Zette returned to Chamonix in the summers where she spent her afternoons in an armchair, sewing and embroidering tea-towels. She never talked about her life as an artist, remaining a dignified, elegant and gentle old lady until the end’.

Much of the information about Suzanne Meunier’s life and work comes from Daniel Auliac’s 2013 study, Suzanne Meunier: une artiste à (re)découvrir.

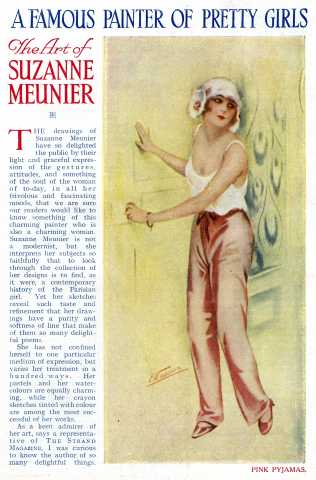

Here is the complete text of the December 1923 Strand Magazine article about Suzanne Meunier:

A FAMOUS PAINTER OF PRETTY GIRLS

A FAMOUS PAINTER OF PRETTY GIRLS

The art of Suzanne Meunier

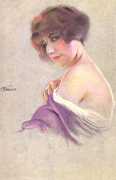

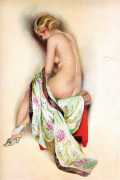

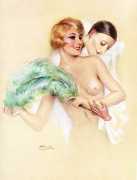

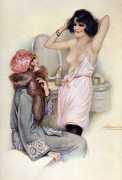

The drawings of Suzanne Meunier have so delighted the public by their light and graceful expression of the gestures, attitudes, and something of the soul of the woman of today, in all her frivolous and fascinating moods, that we are sure our readers would like to know something of this charming painter who is also a charming woman. Suzanne Meunier is not a modernist, but she interprets her subjects so faithfully that to look through the collection of her designs is to find, as it were, a contemporary history of the Parisian girl. Yet her sketches reveal such taste and refinement that her drawings have a purity and softness of line that make of them so many delightful poems.

She has not confined herself to one particular medium of expression, but varies her treatment in a hundred ways. Her pastels and her watercolours are equally charming, while her crayon sketches tinted with colour are among the most successful of her works.

As a keen admirer of her art, says a representative of The Strand Magazine, I was curious to know the author of so many delightful things.

Suzanne Meunier is living at present in Alsace, and I took advantage of a visit to Strasbourg to call on her and ask for an interview. I was charmed at my reception. Suzanne Meunier is quite young; her face is so ‘spirituelle’, so alight with intelligence, that one almost forgets how pretty she is, so greatly is one charmed to find the same feminine note of elegance as that portrayed in her art.

As one looks round her studio, with its walls hung with delicate pastels and soft-hued hangings – the old Louis XV Breton bed transformed into a divan – the open piano within reach – the cushions heaped up everywhere in an harmonious riot of colour – one realizes what a perfect setting it is for its owner – and how much her dual personality of artist and woman has contributed to her success.

She immediately put me at my ease and proceeded to answer my questions with great good nature and simplicity.

‘My vocation,’ she told me, ‘has shown itself from my infancy. While I was still quite tiny I used to cover with quaint designs all the doors and the backs of the cupboards.’

‘Your parents must have been delighted with your precocious leanings towards Art?’

‘Yes,’ she replied, smilingly, ‘but they didn’t let me see it. Often I was deprived of my dessert, or received a sharp rebuke, even a mild box on the ear, as a reward for these childish efforts.

‘At school my rough notebooks were adorned with sketches from cover to cover, and as teachers are not as a rule noted for their sympathy with the picturesque. I was looked upon as a deplorable pupil. But while my notebooks were being covered with little figures it must be owned that my career was taking shape, and as soon as I left school I entered the Academy Julian, where I began my first serious studies.’

‘You were a good pupil there, I am sure,’ I remarked.

‘Yes,’ she smiled, ‘that was quite a different story. I at once showed a marked aptitude for studies of figure work, nothing fascinated me more than to get the real expression of the eyes, the mysterious subtlety of features, the sheen and the wave of the hair. When I was twenty I became a member of the Society of Woman Painters — I exhibited at their Salon in 1909. Then I gave in my resignation, as I wished to travel.’

‘To Italy?’

‘No, to Spain. There is nothing like travel to give experience and to develop the character when one is young, especially in the case of a young artist. I entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts at Barcelona. I gained a prize there and exhibited at the International Exhibition of 1911.’

I remarked that she did not lose any time. ‘There is never any time to lose,’ she said, quickly. ‘After two years’ stay in Spain I returned to Paris, and in 1916 the Galerie Joubert published my colour drawings, the series of which is known to you. The subject of all of them is the Parisian girl – impertinent and mischievous, but whose most audacious moods and gestures are tinged with a grace all her own.

‘At the same time I did not give up my portrait work. I did numerous pastels, seeking all the time to obtain luminous effects, and in 1920 I exhibited at Bordeaux a series of drawings of women’s heads, which achieved great success, since not one of my pictures came back to me – each one found a buyer.

‘The critics of the art world were very kind to me. Here is a cutting which I have kept, since it marked my first great success: “A series of pastels signed Suzanne Meunier is remarkable for the clever ingenuity of the setting – and the captivating spontaneity of their arrangement. The refined charm of these artistic designs is not wholly intellectual – there is also a delicacy of expression in the varied treatment of her subject and a lightness of touch in her wonderful technique – so bewitching yet so restrained. But how modern and true to life they are! Success has come to her quickly and is acknowledged by connoisseurs and artists alike. Suzanne Meunier! Here is a name of a portraitist to be remembered alike in galleries and drawing-rooms.”’

‘One has to get known everywhere,’ continued my hostess, as I handed back the cutting. ‘I have also my public at Nancy, where I exhibit regularly each year at the Exhibition of the Amis des Arts.’

I murmured that she was not unknown in England, and she owned smilingly that she had been much amused at letters from unknown English admirers of her work requesting a signed photograph. She confided to me, too, that she hopes one day to hold an exhibition in London, and I assured her that such a step would delight her English admirers.

I suggested that she must work hard, as I had seen numerous examples of her work.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘I work all the time – I like nothing better, as I am devoted to my art. I know no greater joy than to create beautiful silhouettes, to draw pretty faces with laughing or tender eyes – to see the picture I have framed in my mind grow under my pencil. I have a deep love of beauty, and therefore I choose lovely models – the harsh and the grotesque do not appeal to me. I prefer pleasing types.

‘Of course, I am always taking notes. I carry with me a little notebook in which I draw an enormous number of sketches from life. These are quickly done. In three pencil strokes I jot down for reference the supple curve of a hip or a shoulder, a youthful neck, or a vivacious profile under a hat. I sketch at the theatre, at the restaurant – everywhere, in fact.’

‘But you surely take some recreation?’

‘I play tennis, I motor, I am keen on mountaineering and flying, and, of course, on those occasions my notebook remains in my bag.’

I suggested that an artist like herself must have numerous social obligations. She shook her head emphatically and assured me that she goes out very little and studiously avoids visits and receptions – in that way she has time to read a great deal and to enjoy her music. When she volunteered that Chopin was her favourite composer – Chopin, the great interpreter of women’s moods and passions – I was struck once more by the harmony of her tastes with their expression in her art.

She told me that, like English women, she was very interested in her home, adding that her husband, whom she married in 1920, was of English extraction. And, in fact, the arrangement of fine old furniture in her house bore evidence to the artistic taste of the owner – even her little black and white cat, Mitsou, which, she told me, sleeps for hours on her knees while she works, added a home-like touch to her surroundings. She insisted that, contrary to the accepted idea, the life of a married woman is not incompatible with that of an artist, and that her output of work has remained the same since her marriage.

‘What are your plans?’ I asked her.

‘To go on with my art – and, in fact, the path is already marked out. For quite a long time now I have been associated with the Librairie de l’Estampe, which reproduces my pastels and watercolours to perfection, and I contribute regularly to the artistic publication, Eros. This summer also I signed a contract with the Le Sourire, one of the wittiest and most amusing of Parisian magazines.’

I felt as I said goodbye to Suzanne Meunier that here at last I had met someone in whom the artist and the woman were perfectly balanced. Her designs speak for themselves – they have a special and personal charm typical of their author, a modern woman, acute of perception and with the soul of an artist, piquant as the subjects of her pictures, the gay, spirited, and lovely girls of the Paris of today.