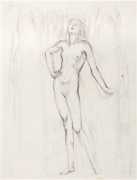

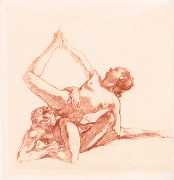

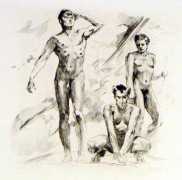

Alméry Lobel-Riche, believed by many to be at the pinnacle of early twentieth-century French etchers, was born Alméric Joseph Riche in Geneva, Switzerland, and grew up in Montpellier. Though his mother came from an upper-class Provence family, the family was not rich, so after a short time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier Alméry went to Paris to find work. While still in Montpellier, he had made the acquaintance of a doctor from the Faculty of Medicine who was writing a textbook on anatomy and was looking for an illustrator; working on these illustrations gave the young Lobel-Riche a deep knowledge of the structure of the human body.

Alméry Lobel-Riche, believed by many to be at the pinnacle of early twentieth-century French etchers, was born Alméric Joseph Riche in Geneva, Switzerland, and grew up in Montpellier. Though his mother came from an upper-class Provence family, the family was not rich, so after a short time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Montpellier Alméry went to Paris to find work. While still in Montpellier, he had made the acquaintance of a doctor from the Faculty of Medicine who was writing a textbook on anatomy and was looking for an illustrator; working on these illustrations gave the young Lobel-Riche a deep knowledge of the structure of the human body.

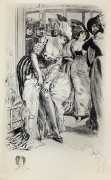

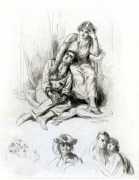

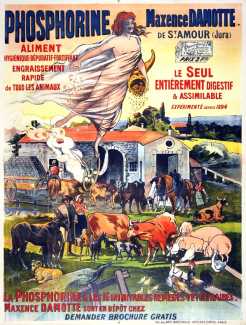

For a few years in Paris he worked as an architect’s assistant, lithographer, poster designer and occasional press illustrator, at the same time attending classes with Léon Bonnat, Paul Saïn, and Antoine Calbet at the École des Beaux-Arts, and visiting museums and galleries. He started exhibiting at the Paris Salon des Artistes Français of 1902, and was fortunate to be noticed and commissioned by the publisher Ollendorf to illustrate La main gauche (The Left Hand), a collection of stories by Guy de Maupassant.

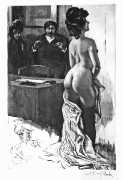

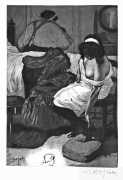

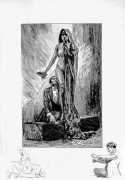

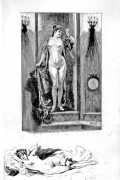

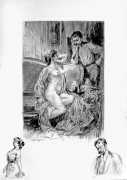

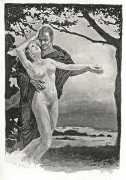

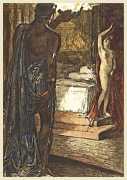

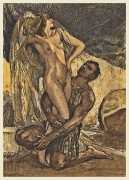

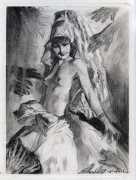

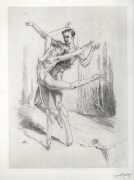

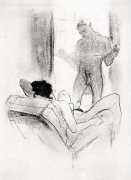

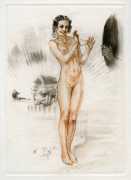

During the early years of the new century he worked hard at perfecting his etching skills, concentrating more on this than on painting. Recognising through the work of Auguste Brouet, Felicién Rops and Louis Legrand that the subtleties of the form captured best the lively Paris scene he wanted to illustrate, he produced many detailed etchings of city life. In 1907 he married Solange Paviot (1877–1960) and they moved above his studio in Montmartre, from where he found many of the models for his trademark etchings of scantily-clad women. From this highly-productive period come his portfolios Études de filles (1909), Les diaboliques (1910), and Poupées de Paris (1912).

Then came the war. Mobilised in 1914, he was made a lieutenant in Macedonia, where he spent some of the time painting and drawing, but in 1917 caught typhus and was some time in hospital before spending the last six months of the war in Morocco with Marshal Lyautey, where he continued to draw and paint. Ten years later many of his drawings would be used to illustrate André Chevrillon’s Un crépuscule d’Islam (A Twilight of Islam).

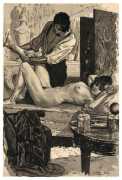

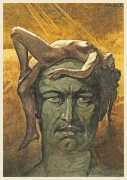

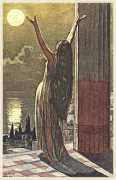

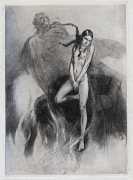

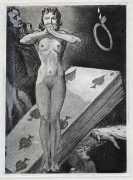

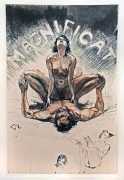

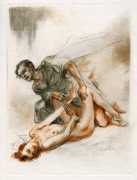

Like so many of his generation, the experiences of war and a much-changed Paris led Lobel-Riche to deep introspection, finding common cause with poets like Baudelaire and novelists like Mirbeau. Fortunately for the talented engraver, the 1920s also saw the extraordinary vogue of the limited-edition luxury illustrated book, so he was never short of new commissions. His subject matter gradually became darker and more symbolic, and though female nudity was still present it now often had overtones of menace and death.

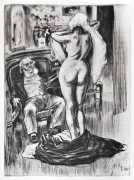

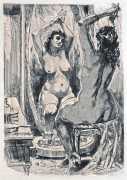

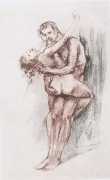

In July 1936 Alméry and Solange divorced, and later that year he married Odette Vandal (1904–97); intriguingly this is the period from which came many of the etchings for his most sexually-explicit portfolios, Arabesques intimes and Nouveaux méandres intimes, both published privately.

The renewed threat of war in 1939 again affected Lobel-Riche’s outlook and artistic style, moving to sparser, cleaner drawing and new muses, especially the poetry of Paul Verlaine. In June 1940 Alméry and Odette left Paris to take refuge in her home town of Corrèze in south-western France. As his etching materials had of necessity been left in Paris, he returned to painting and drawing, demonstrating that he had lost none of his talent in these media.

In 1946 his friend, the art critic Robert Margerit, wrote the text for an illustrated appreciation of Alméry Lobel-Riche’s life and work, calling him ‘one of the greatest artist-engravers of all time’.