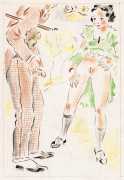

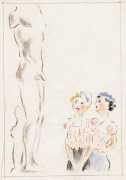

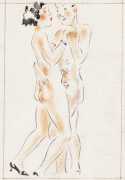

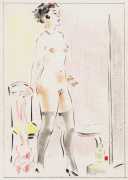

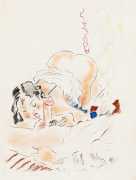

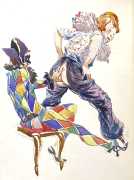

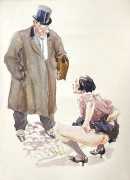

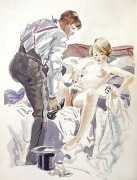

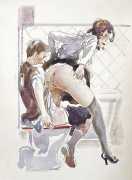

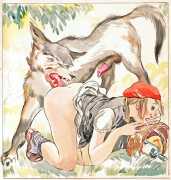

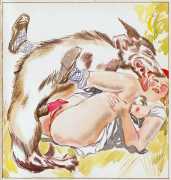

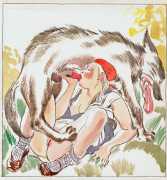

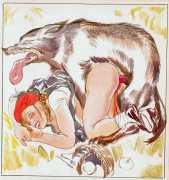

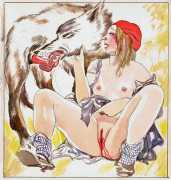

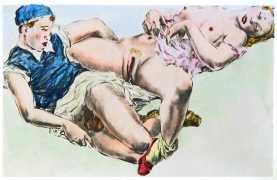

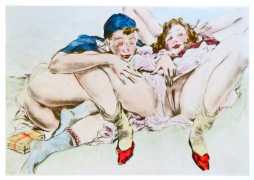

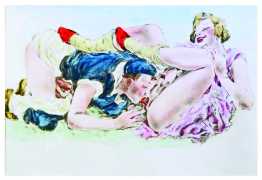

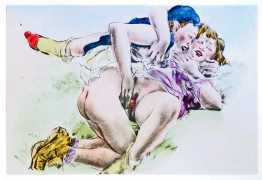

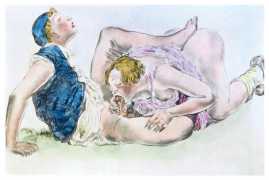

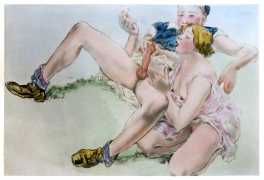

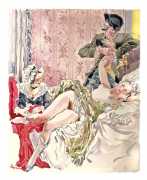

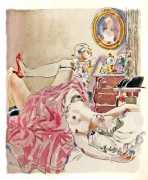

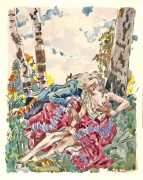

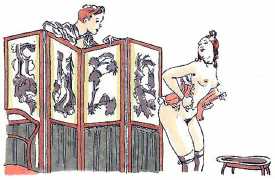

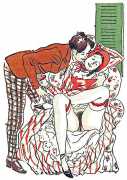

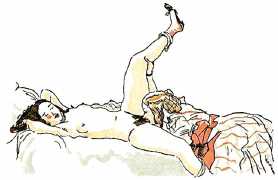

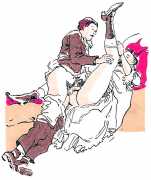

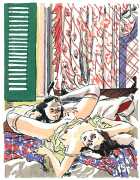

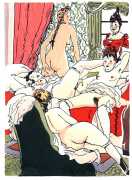

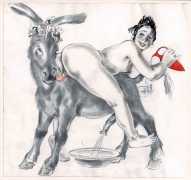

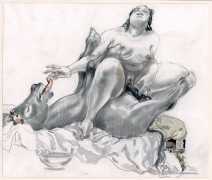

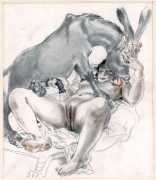

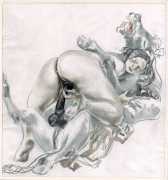

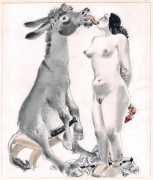

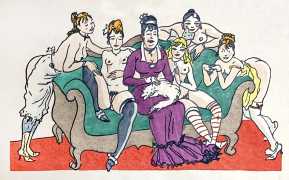

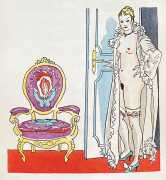

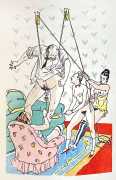

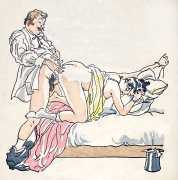

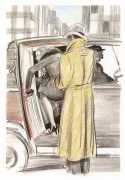

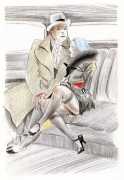

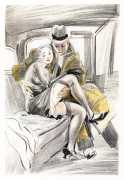

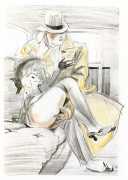

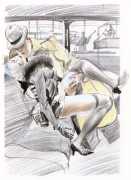

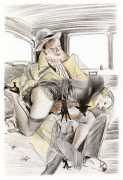

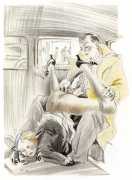

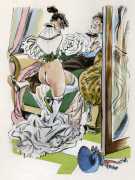

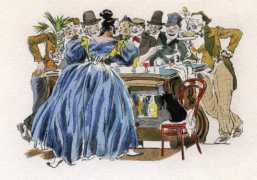

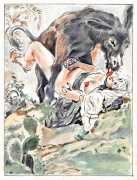

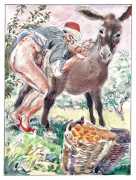

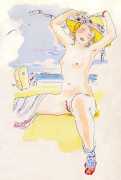

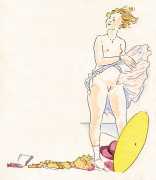

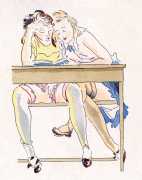

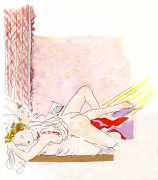

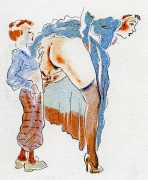

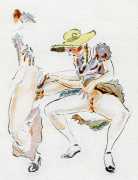

In their comprehensive biography of the talented and versatile Russian-born illustrator Feodor Rojankovsky, Allen and Polly Irving write: ‘The naughty books are a minor but noteworthy aspect of the illustrator’s long and varied career and round out the picture of a man in and of his time and place. The drawings are best viewed in the cultural setting of Paris in the 1930s and, in the much harsher world of today, appreciated for their gentle period style and what they reveal of our social and cultural history.’

In their comprehensive biography of the talented and versatile Russian-born illustrator Feodor Rojankovsky, Allen and Polly Irving write: ‘The naughty books are a minor but noteworthy aspect of the illustrator’s long and varied career and round out the picture of a man in and of his time and place. The drawings are best viewed in the cultural setting of Paris in the 1930s and, in the much harsher world of today, appreciated for their gentle period style and what they reveal of our social and cultural history.’

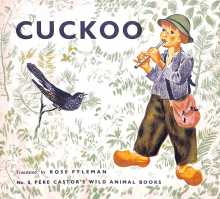

While it is true that many readers will remember Rojankovsky as the kindly children’s storytelling beaver Père Castor, and author of many of the Little Golden Books of the 1950s, published so successfully by Simon & Schuster that first print runs of 500,000 copies were common, that was not where he started his career, and not what those who know Rojan best for his trademark ‘naughty’ work are most familiar with. Downplaying those formative years in Paris is to overlook how his prodigious talent and experience were nurtured and honed. To be fair to the Irvings, they do say ‘This small and generally amusing body of work has long been known, valued, and collected; Rojankovsky lavished his best draftsmanship and colour work on these illustrations and they are among his most accomplished work.’

Rojankovski’s life neatly divides into three periods, the Russia/Poland years up until 1925; the Paris period from 1925 to 1941; and the rest of his life in America. All were characterised by an incredible productivity, and each contributed to his distinctive, brightly-coloured, spirited and stylish art. Here we concentrate on the erotic portfolios of his Paris years, though the list of works below shows that Rojan (the shortened version of his name he adopted when he arrived in France) was still producing some erotica after his wartime exodus to the USA.

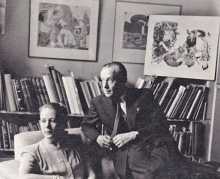

Irving and Polly Allen have written an excellent survey of Rojan and his work – Feodor Rojankovsky: The Children’s Books and Other Illustration Art was published by Wood Stork Press in 2013. The extracts below are reproduced, much-abridged, from their book, which is well worth reading as much for its insights into how illustrators and publishers worked together in the mid-twentieth century as it is for Rojankovsky’s life story.

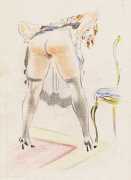

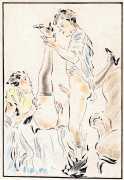

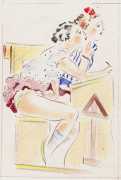

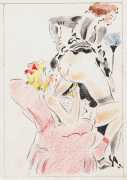

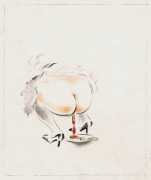

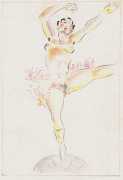

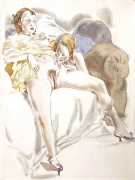

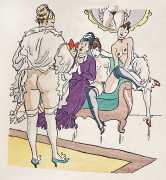

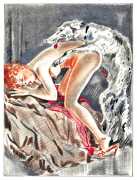

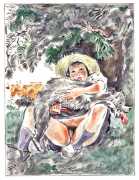

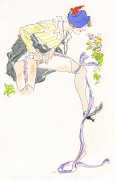

One of Rojankovsky’s favourite models in Paris was Anastasia (Nastenka) Minsekova, a young ballet student of Russian background who in the 1950s became a published illustrator. For several sketches and watercolours in the late 1930s, Rojankovsky drew Nastenka, Degas-like in a tutu, usually standing and viewed from the rear, and sometimes spied in informal moments.

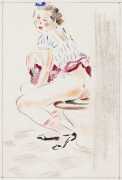

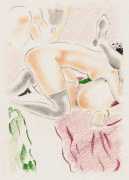

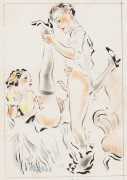

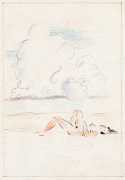

In 1930 Rojankovsky and a friend from his time in the Ukraine after the Revolution, the Russian sculptor Lev Schultz, took a trip to Algiers. Rojankovsky kept snapshots of himself and Schultz in a local park with a pretty algérienne model, she obligingly in native costume. It was surely she who posed in a harem outfit, bare-breasted, baggy pantaloons and all, for Rojan to paint; he reworked one such figure study for Béranger’s Chansons galantes.

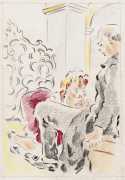

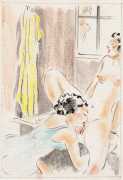

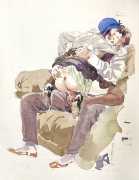

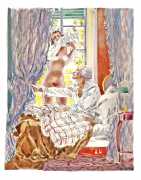

About 1931 Rojankovsky met Yvette, an attractive and well-composed Frenchwoman in her middle to late thirties, permanently separated from her husband and with a nearly grown son. Rojankovsky and Yvette set up house and remained together for ten years until he left France in 1941. Yvette’s surname is lost to us and we know little about her except for a few photographs and distant recollections of several people who met her in the 1930s. The writer Olga Andreyev Carlisle met the couple in the mid-1930s when they were neighbours at Plessis-Robinson. Through the eyes of a Russian child, Carlisle remembers Yvette as ‘exotically French with lots of Paris chic’.

Beginning in 1935, Rojankovsky and Yvette began vacationing in Argentière, a resort community nestled in the French Alps near Chamonix Mont-Blanc in the Savoie region and near the Swiss and Italian frontiers. For several years they rented with a farm family named Couttet, but soon entertained plans for a house of their own. On a nearby property Rojankovsky bought built a tiny Alpine-style house, named Villa Rambles, intended as a respite from workaday Paris. The house was not completed until sometime in 1940. Rojankovsky was to live in it only for a few months before Paris fell to the Germans and he realised that he had to leave Europe as quickly as possible.

Georges Duplaix, Rojankovsky’s French editor, had been in the United States since 1931; in early 1940 he was hatching plans to produce Golden Books for Simon & Schuster, and working through the New York agent, Josef Riwkin, Duplaix engaged Rojankovsky to come and work in New York. While the occupying Germans and their French collaborators in Vichy had no particular interest in Rojankovsky, Russians were generally a suspect foreign element in France, so in the summer of 1941 he made his way southward through Vichy France and across Spanish frontier to Cadiz. Rojankovsky’s declared intention was to return to Paris and to Yvette, but he could not have anticipated how long the war would last or how his life would change in America. He sent Yvette money and they exchanged letters, but his immigration status did not permit him to travel until 1948, and by then everything had changed. It was not until 1951 that he returned to France – with a wife and young child.

He booked passage on a Spanish ship scheduled to sail on July 10th, with New York as its final destination, but the departure was delayed nearly a month and, low on funds, he became stranded in a small hotel. Always resourceful, he struck a deal to paint murals for the hotel’s owner in exchange for rent, meals, and a daily bottle of vino fino. Eventually Rojan arrived in New York on September 12th. Arrival records show that, as Rojankovsky was processed through immigration, he declared $60 in cash and told officials that he would go directly to stay with the agent Josef Riwkin in Greenwich Village until he found his own apartment.

In the mid-1940s Rojankovsky summered in Bar Harbor, Maine and skied in Stowe, Vermont. Nina Fedotova, whom he had first met years earlier as a young woman in France, he now met again in New York, and they became engaged. They married in April of 1946 and resided in a brownstone apartment on West 9th Street. Two years later the couple’s daughter Tatiana (Tanya) was born. Rojankovsky had never cut emotional ties in Europe, where he left many friends and interests. With his family, he began to travel to France every year, staying a year or more on two trips in the 1950s, and he also went to Russia every two years or so until the end of his life. In the early 1950s the Rojankovskys bought land and built a second home near the Russian colony at La Favière on the French Riviera.

After returning from their second trip to France in late 1953, they bought a house in Bronxville, New York, at the suggestion of a friend, the Russian émigré critic and writer Marc Slonim, whom Rojankovsky in the 1930s had known in Paris and who was now teaching at a college nearby. Six years later, in 1960, they sold the house in Bronxville and the family of three moved to France, staying for five years. In 1965 and now in his seventies, Rojankovsky brought the family back to the United States; eye surgery done in France in 1964 had to be repeated a year later in the USA, and as a result his work had been slowed. The Rojankovskys settled again in Bronxville, where he spent his last years. Rojankovsky always and above all considered himself a Russian, though one in exile, and so an accidental citizen of the world. He did not become a naturalized US citizen until 1968, only two years before his death in 1970, and then more for practical reasons than indicating a new national identity.

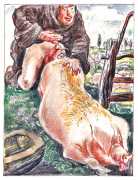

Here is a list of all the erotic titles illustrated by Rojan

(the Dutel numbers refer to the relevant entry in Jean-Pierre Dutel’s Bibliographie des ouvrages érotiques publiés clandestinement en Français entre 1920 et 1970, published in 2005; the Nordmann numbers to the 2006 auction catalogues of the Gérard Nordmann collection)

1926, Pierre Louÿs, Manuel de civilité pour les petites filles, twenty colour illustrations, Dutel 1916, extra-illustrated copy at Nordmann 1/315

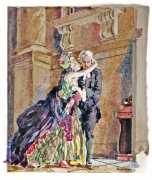

1929, Andréa de Nerciat, Félicia, colour illustrations, extra-illustrated copy at Nordmann 1/23

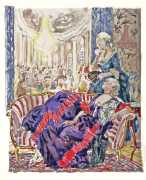

1932, Le théâtre érotique de la Rue de la Santé, twenty colour illustrations, Dutel 2498

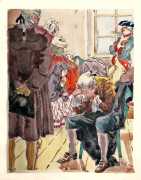

1935, Louis Protat, Examen de Flora, fourteen colour illustrations, Dutel 1532

1935, Théophile Gautier, Poésies libertines, eight colour illustrations

1935–7, Raymond Radiguet, Vers libre, 27 or 31 colour illustrations, Dutel 2592–3

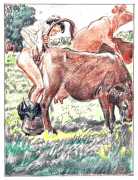

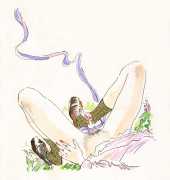

1936, Idyll printanière, 31 colour illustrations, Dutel 1726–7

1937, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Chansons galantes, sixteen colour illustrations

1937, Pierre Louÿs, Poèsies erotiques, 73 sanguine illustrations, Dutel 2230

1940, Vicomtesse de Saint Luc, Liqueurs féminines, parfums sexuels, twelve colour illustrations, Dutel 1856

1940, Pierre Louÿs, Trois filles de leur mère, also with illustrations by Berthommé and Collot, Dutel 2526

1948, Jean Spaddy, Dévergondages, sixteen colour illustrations, Dutel 1389

(not published)

Andréa de Nerciat, Mon noviciat ou les joies de Lalotte, 145 watercolours for Gérard Nordmann, Nordmann 2/18

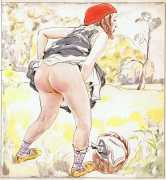

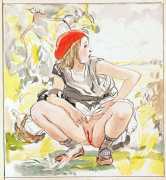

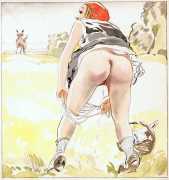

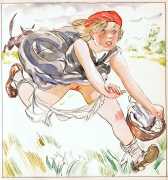

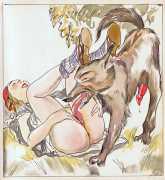

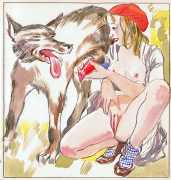

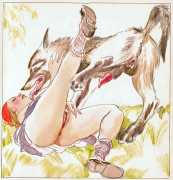

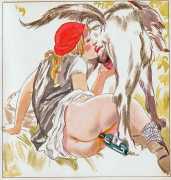

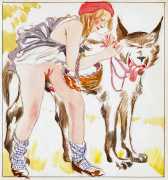

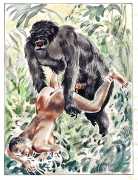

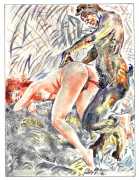

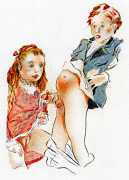

Le petit chaperon rouge (Little Red Riding Hood), eighteen illustrations for Gérard Nordmann, Nordmann 2/357

Guillaume Apollinaire, Cortège priapique, ten illustrations for Gérard Nordmann, Nordmann 1/30